Contd from previous issue :

His outstanding judicial career and landmark judgments have made him well known within the legal arena. Through his bravery and boldness, he placed himself in the legal history.

Justice Mustafa Kamal was a pioneer in establishing and promoting the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). In 2003, he was appointed as a Consultant for ADR by the then government and he had taught modules on ADR in 64 districts of the country. He may, thus, be called the ‘Founder of the ADR’ in Bangladesh.

He attended various international seminars and symposia held at prestigious locations and gave speeches on ADR.

Justice Mustafa Kamal was the most talented judge of our time. He would be remembered for many things. Among them was his landmark judgment on the case of Secretary, Ministry of Finance v Masdar Hossain (1999) 52 DLR (AD) 82 (popularly known as the Masdar Hussain’s Case) which was a milestone in the quest for the separation of power between the judiciary ad the state and the independence of judiciary in Bangladesh. The landmark decision was determined on the question of to what extent the constitution of the Republic of Bangladesh has actually ensured the separation of judiciary from the executive organs of the State. In essence, the case was decided on the issue of how far the independence of judiciary is guaranteed by our Constitution and whether the provisions of the Constitution have been followed in practice. In the leading judgement, he directed the Government to implement its twelve point directives, including the formation of separate Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to carry out the appointment, promotion and transfer of members of the judiciary in consultation with the Supreme Court. Further directives called for a separate Judicial Service Pay Commission, amendment of the criminal procedure and the new rules for the selection and discipline of members of the Judiciary.

On an extensive examination of constitutional provisions relating to subordinate courts (Article 114-116A) and services of Bangladesh (Article 133-136), the Appellate Division headed by Justice Mustafa Kamal held that “judicial service is fundamentally and structurally distinct and separate service from the civil executive and administrative services of the Republic with which the judicial service cannot be placed on par on any account and that it cannot be amalgamated, abolished, replaced, mixed up and tied together with the civil executive and administrative services.” (Para 76). It also directed the government for making separate rules relating to posting, promotion, grant of leave, discipline, pay, allowance, pension and other terms and condition of the service consistent with Article 116 and 116A of the constitution.

However, in delivering judgment, Justice Mustafa Kamal made an attempt to differentiate between the terms ‘independence’ and ‘impartiality’ and said obiter that he would subscribe to the view of a leading decision of Supreme Court of Canada in Walter Valente v Her Majesty the Queen (1985) 2 SCR 673, on protection of judicial independence under Section ii (a) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Walter Valente held that “the concepts of ‘independence’ and ‘impartiality,’ although obviously related, are separate distinct values or requirements.’ ‘Impartiality’ refers to a state of mind or attitude of the tribunal in relation to the issues and the parties in a particular case. ‘Independence’ reflects or embodies the traditional constitutional value of judicial independence and connotes not only a state of mind but also a status or relationship to others … particularly to the executive branch of government …”

Unfortunately, subsequent governments have failed to implement the judgment in a true and literal sense. The last military-backed Interim Government took a positive stance to separate the judiciary from the executive based on the principles of constitutional directive and Appellate Division’s judgment in the Masder Hossain’s Case. Accordingly, the following four service rules were enacted and changes were bought in the existing Code of Criminal Procedure 1898 by Ordinance No II and No IV of 2007:

(a) Bangladesh Judicial Service Commission Rules, 2007;

(b) Bangladesh Judicial Service (Pay Commission) Rules 2007,

(c) Bangladesh Judicial Service Commission (Construction of Service, Appointments in the Service and Suspension, Removal & Dismissal from the Service) Rules, 2007; and

(d) Bangladesh Judicial Service (Posting, Promotion, Grant of Leave, Control, Discipline and other Condition of Service) Rules, 2007.

This was considered to be a major change paving the way for dispensation of Criminal Justice at the level of magistracy by the officers belonging to Bangladesh Judicial Service and thereby removing all impediments in the separation of Judiciary from the executive control. At last, after a long journey, the judiciary was separated from the executive and started functioning independently from 1st November 2007. However, when the next political government came to office, they were reluctant to implement and follow the judgment fully. They did not approve or carry on the steps taken by the military-backed Interim Government. Recent politicisation of the judiciary has made the matters worse. Because of political maneuvourng by, bureaucratic complexities and short-sightedness of the subsequent governments, the judiciary has not been independent and the separation of power has not been materialised, as envisaged by the judgment of Masdar Hussain’s Case. This is very unfortunate for the nation.

Another great contribution by Justice Mustafa Kamal came when a Writ Petition was filed by an NGO (which appeared to be anti-Islamic) seeking cancellation and/or amendment of the Quranic provision of the iddat, a specific period during which a husband, after divorce, is required to support his wife. The High Court judges gave their judgment against the Quranic provision of the Iddat. The matter went to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court by way of appeal. Justice Mustafa Kamal played an active role in dismissing the High Court’s judgment. The Appellate Division called two religious scholars to give expert opinion. Justice Mustafa Kamal played so active role that he was able to convince a non-Muslim Judge of the then Appellant Division of the Supreme Court and secure a unanimous judgement. In his judgment he strongly condemned High Court Judges’ ignorance of basic Islamic knowledge, norms and philosophy.

I have very good memories of Justice Mustafa Kamal. I was lucky to have met him three times in London and spent hours with him. I visited the house where he lived and had dinner with him. I was planning to have dinner with him at a prestigious restaurant, but he was keen to go to Bangla Town to have spacious Bengali food. Accordingly, we went there and enjoyed a genuine (khati), ordinary – but very delicious – Bengali food. While having foods, he described how difficult it was to find halal foods and mosques and/or prayer places in London during the 1950s when he was studying at LSE and for the Bar. I organised a roundtable discussion on the ‘Separation of Power and Independence of the Judiciary’ in London in 2005, which was attended by more than 100 professionals at short (24 hours) notice. Justice Mustafa Kamal gave an hour long in-depth lecture as the Chief Guest. The following week, a leading Bengali weekly made his speech a six column wide lead news story. Before this programme, he gave an interview to the BBC Bangla World Service on the independence of the judiciary, separation of powers and judicial activism.

Justice Mustafa Kamal shared many things during my hours’ long association with him. I found him as a free and straightforward sharp intellectual, full of wisdom and talent. His analytical power and style of expression were extraordinary. He once said, “Nazir, I gave the judgment [leading judgment] in Masdar Hussain’s Case for the greater interest of the nation and its constitution. The country would be better off if the subsequent governments implemented and followed the judgment completely and fully.”

He mentioned and praised some lawyers of the Supreme Court and at the same time he expressed concerns about the integrity and honesty of some lawyers – but I shall refrain myself from mentioning their names as they are still alive and practising.

In relation to some competent Advocates of the Supreme Court, he said, “They are competent lawyers at international standard and can easily compete with any competent lawyers of any developed countries of the world.”

On one occasion, Justice Kamal said, “ism – such as socialism, capitalism, communism – should never be in the constitution. If these were in the constitution, political tension, dreadlock and unnecessary debates would never end. [The] constitution is an operative document and democracy and democracy alone should be in it. Whichever party comes to office, with people’s mandate, will run the country in accordance with its political ideology or ism.” This is the scenario and position taken by a renowned writer and politician Abul Monsur Ahmed in his book called Aamar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor (Fifty years of my sight of politics). It shows what an extraordinary wisdom and far sighted mentality Justice Mustafa Kamal had.

Personally Justice Mustafa Kamal was a pious man, but he was liberal, respectful and accommodative in his thinking and approach.

In his personal life, he followed Islamic teachings, customs and norms. He was regular in prayers. He used to say “prayers (salat/namaj) are the dues of the body.”

Bangladesh truly missed one of its most talented judges in its 44 years history January 5, 2016 is his first death anniversary. May Allah (SWT) give him high rewards in the hereafter. n

His outstanding judicial career and landmark judgments have made him well known within the legal arena. Through his bravery and boldness, he placed himself in the legal history.

Justice Mustafa Kamal was a pioneer in establishing and promoting the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). In 2003, he was appointed as a Consultant for ADR by the then government and he had taught modules on ADR in 64 districts of the country. He may, thus, be called the ‘Founder of the ADR’ in Bangladesh.

He attended various international seminars and symposia held at prestigious locations and gave speeches on ADR.

Justice Mustafa Kamal was the most talented judge of our time. He would be remembered for many things. Among them was his landmark judgment on the case of Secretary, Ministry of Finance v Masdar Hossain (1999) 52 DLR (AD) 82 (popularly known as the Masdar Hussain’s Case) which was a milestone in the quest for the separation of power between the judiciary ad the state and the independence of judiciary in Bangladesh. The landmark decision was determined on the question of to what extent the constitution of the Republic of Bangladesh has actually ensured the separation of judiciary from the executive organs of the State. In essence, the case was decided on the issue of how far the independence of judiciary is guaranteed by our Constitution and whether the provisions of the Constitution have been followed in practice. In the leading judgement, he directed the Government to implement its twelve point directives, including the formation of separate Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to carry out the appointment, promotion and transfer of members of the judiciary in consultation with the Supreme Court. Further directives called for a separate Judicial Service Pay Commission, amendment of the criminal procedure and the new rules for the selection and discipline of members of the Judiciary.

On an extensive examination of constitutional provisions relating to subordinate courts (Article 114-116A) and services of Bangladesh (Article 133-136), the Appellate Division headed by Justice Mustafa Kamal held that “judicial service is fundamentally and structurally distinct and separate service from the civil executive and administrative services of the Republic with which the judicial service cannot be placed on par on any account and that it cannot be amalgamated, abolished, replaced, mixed up and tied together with the civil executive and administrative services.” (Para 76). It also directed the government for making separate rules relating to posting, promotion, grant of leave, discipline, pay, allowance, pension and other terms and condition of the service consistent with Article 116 and 116A of the constitution.

However, in delivering judgment, Justice Mustafa Kamal made an attempt to differentiate between the terms ‘independence’ and ‘impartiality’ and said obiter that he would subscribe to the view of a leading decision of Supreme Court of Canada in Walter Valente v Her Majesty the Queen (1985) 2 SCR 673, on protection of judicial independence under Section ii (a) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Walter Valente held that “the concepts of ‘independence’ and ‘impartiality,’ although obviously related, are separate distinct values or requirements.’ ‘Impartiality’ refers to a state of mind or attitude of the tribunal in relation to the issues and the parties in a particular case. ‘Independence’ reflects or embodies the traditional constitutional value of judicial independence and connotes not only a state of mind but also a status or relationship to others … particularly to the executive branch of government …”

Unfortunately, subsequent governments have failed to implement the judgment in a true and literal sense. The last military-backed Interim Government took a positive stance to separate the judiciary from the executive based on the principles of constitutional directive and Appellate Division’s judgment in the Masder Hossain’s Case. Accordingly, the following four service rules were enacted and changes were bought in the existing Code of Criminal Procedure 1898 by Ordinance No II and No IV of 2007:

(a) Bangladesh Judicial Service Commission Rules, 2007;

(b) Bangladesh Judicial Service (Pay Commission) Rules 2007,

(c) Bangladesh Judicial Service Commission (Construction of Service, Appointments in the Service and Suspension, Removal & Dismissal from the Service) Rules, 2007; and

(d) Bangladesh Judicial Service (Posting, Promotion, Grant of Leave, Control, Discipline and other Condition of Service) Rules, 2007.

This was considered to be a major change paving the way for dispensation of Criminal Justice at the level of magistracy by the officers belonging to Bangladesh Judicial Service and thereby removing all impediments in the separation of Judiciary from the executive control. At last, after a long journey, the judiciary was separated from the executive and started functioning independently from 1st November 2007. However, when the next political government came to office, they were reluctant to implement and follow the judgment fully. They did not approve or carry on the steps taken by the military-backed Interim Government. Recent politicisation of the judiciary has made the matters worse. Because of political maneuvourng by, bureaucratic complexities and short-sightedness of the subsequent governments, the judiciary has not been independent and the separation of power has not been materialised, as envisaged by the judgment of Masdar Hussain’s Case. This is very unfortunate for the nation.

Another great contribution by Justice Mustafa Kamal came when a Writ Petition was filed by an NGO (which appeared to be anti-Islamic) seeking cancellation and/or amendment of the Quranic provision of the iddat, a specific period during which a husband, after divorce, is required to support his wife. The High Court judges gave their judgment against the Quranic provision of the Iddat. The matter went to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court by way of appeal. Justice Mustafa Kamal played an active role in dismissing the High Court’s judgment. The Appellate Division called two religious scholars to give expert opinion. Justice Mustafa Kamal played so active role that he was able to convince a non-Muslim Judge of the then Appellant Division of the Supreme Court and secure a unanimous judgement. In his judgment he strongly condemned High Court Judges’ ignorance of basic Islamic knowledge, norms and philosophy.

I have very good memories of Justice Mustafa Kamal. I was lucky to have met him three times in London and spent hours with him. I visited the house where he lived and had dinner with him. I was planning to have dinner with him at a prestigious restaurant, but he was keen to go to Bangla Town to have spacious Bengali food. Accordingly, we went there and enjoyed a genuine (khati), ordinary – but very delicious – Bengali food. While having foods, he described how difficult it was to find halal foods and mosques and/or prayer places in London during the 1950s when he was studying at LSE and for the Bar. I organised a roundtable discussion on the ‘Separation of Power and Independence of the Judiciary’ in London in 2005, which was attended by more than 100 professionals at short (24 hours) notice. Justice Mustafa Kamal gave an hour long in-depth lecture as the Chief Guest. The following week, a leading Bengali weekly made his speech a six column wide lead news story. Before this programme, he gave an interview to the BBC Bangla World Service on the independence of the judiciary, separation of powers and judicial activism.

Justice Mustafa Kamal shared many things during my hours’ long association with him. I found him as a free and straightforward sharp intellectual, full of wisdom and talent. His analytical power and style of expression were extraordinary. He once said, “Nazir, I gave the judgment [leading judgment] in Masdar Hussain’s Case for the greater interest of the nation and its constitution. The country would be better off if the subsequent governments implemented and followed the judgment completely and fully.”

He mentioned and praised some lawyers of the Supreme Court and at the same time he expressed concerns about the integrity and honesty of some lawyers – but I shall refrain myself from mentioning their names as they are still alive and practising.

In relation to some competent Advocates of the Supreme Court, he said, “They are competent lawyers at international standard and can easily compete with any competent lawyers of any developed countries of the world.”

On one occasion, Justice Kamal said, “ism – such as socialism, capitalism, communism – should never be in the constitution. If these were in the constitution, political tension, dreadlock and unnecessary debates would never end. [The] constitution is an operative document and democracy and democracy alone should be in it. Whichever party comes to office, with people’s mandate, will run the country in accordance with its political ideology or ism.” This is the scenario and position taken by a renowned writer and politician Abul Monsur Ahmed in his book called Aamar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor (Fifty years of my sight of politics). It shows what an extraordinary wisdom and far sighted mentality Justice Mustafa Kamal had.

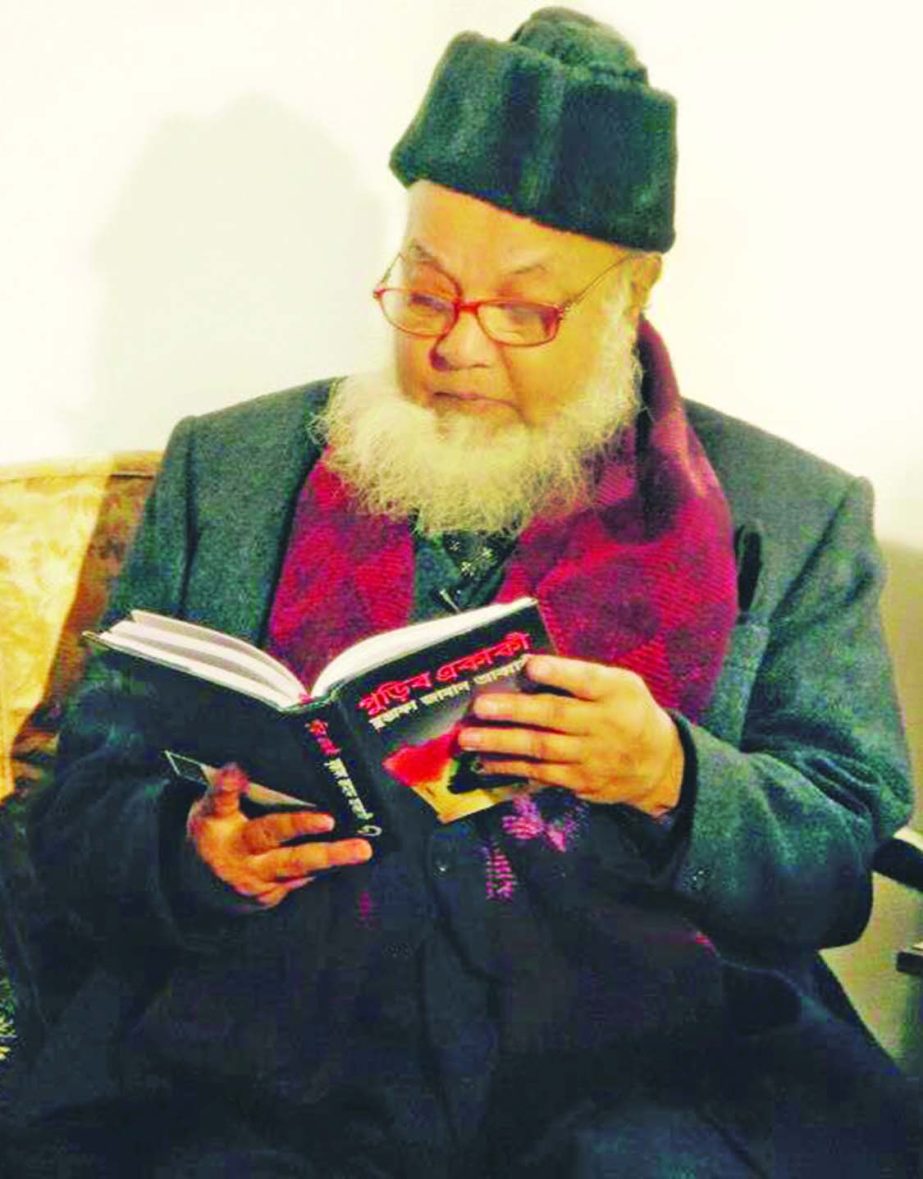

Personally Justice Mustafa Kamal was a pious man, but he was liberal, respectful and accommodative in his thinking and approach.

In his personal life, he followed Islamic teachings, customs and norms. He was regular in prayers. He used to say “prayers (salat/namaj) are the dues of the body.”

Bangladesh truly missed one of its most talented judges in its 44 years history January 5, 2016 is his first death anniversary. May Allah (SWT) give him high rewards in the hereafter. n

(Barrister Nazir Ahmed is UK based legal expert, analyst, writer and columnist)