Pritha Sen :

Mood food is what we Indians thrive on. Like the lovers in Kalidas’ Ritusamhara (Garland of Seasons), our love affair with food and the emotions it evokes changes hues with the seasons. Inexplicable gastronomic longings tug at our heartstrings as the skies darken. It’s the epic season of the Meghdootam and the clouds come bearing tidings of hot masala chai and sizzling pakodas.

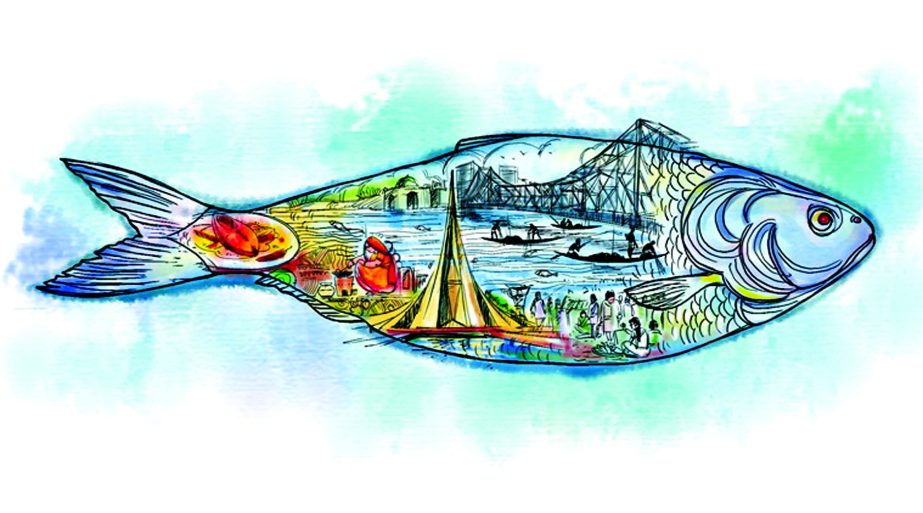

As the first drops of rain promise to turn into a downpour, I throw a casual question at my young friend Ipshita, a trendy woman of the times: “What do you feel like eating?” “Some sort of a roast with herbed potatoes and wine, with Julio Iglesias playing softly in the background,” she says, and then adds in honest admission: “Or, onion fritters with khichdi and fried ilish (hilsa), with some earthy folk music on the side”. Iglesias, take a back seat, the hilsa is programmed into a Bengali’s DNA.

It’s the time of the ilshey guri, the light drizzle heralding the monsoon when the celebrated hilsa, heavy with roe, starts travelling upstream from the sea. Ipshita’s earthy song could well be – Halka haoway megher chhayay/ Ilshey gurir naachh/ Ilshey gurir nachon dekhey/ Nachchey ilish maachh (To the rhythm of a light breeze and the shadow of clouds/ The raindrops prance/ Seeing this delightful sight/ The hilsa fish dance). I have heard many lyrical descriptions of how, when the first drizzles hit the shimmering dark waters, the silvery hilsa spring out and dance delightfully and that’s when the fishermen net them.

As a newcomer in a Kolkata school, I had an epiphany. As I sat alone in a corner of the classroom during lunch break, I watched in fascination a Sindhi classmate unpacking the hot lunch that had just arrived from home. Tucking her serviette firmly in place, she proceeded to attack a large piece of fried hilsa with a fork and spoon. My first thought was how could a “non-Bengali” eat hilsa and that too with a fork? I waited, in morbid anticipation, for her to choke on the first bone. She calmly proceeded to navigate through it expertly, without offering me a single morsel.

The purpose of this little reminiscence is that Bengal claiming sole custodianship of the delicacy called the hilsa has more to do today with the region being the last remaining bastion of a fast dwindling species, than with any unique culinary tradition. The Bengal ilish-mafia is not to be blamed either because just one boneless smoked hilsa popularised by the British Raj in Bengal put the pressure on its people to take ownership and pour out their obsession to the world. Last year, even before the season started in full earnest, one jamai (son-in-law) in Kolkata created news with a Rs 22,000-hilsa on his plate!

The subcontinental hilsa was the king among fish at one time from the Indus in the west to the Cauvery and Godavari in the south, from the Narmada in middle India to the Mahanadi and Brahmani in the south-east, and the Ganga, Padma and Meghna in the east, into Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Stories abound about how the Mughal emperors waited for the silver and vermillion-tinted beauties, as they entered the estuaries through the Arabian Sea on one side and the Bay of Bengal on the other, and swam up from the Bay of Bengal to Kanpur and Allahabad. Clearly, the hilsa once enjoyed an iconic status across India, which, unfortunately, now has shrunk to perhaps just Bengal, Bangladesh and Burma.

Zinda Pir or Jhuley Lal, the mighty Indus deity, worshipped by both Hindus and Muslims, sits on a lotus and rides atop a Palla, the name for the hilsa in Sindh (now in Pakistan). Says Sindhi food expert Alka Keswani: “The fish was sacred for us and termed ‘Darya ka Phool’ (Flowers of the Ocean). Much like the hilsa swims against the tide, the Sindhis, especially after Partition, hold on to the belief that one can rise above the tide.” Interestingly, legendary playwright Habib Tanvir had once likened his art to the hilsa swimming against turbulent currents.

Keswani talks about Thatta, now in Pakistan, where you would get the best hilsa in the world. “There is a Sindhi saying – Pallo seeray khan bhi bhallo/seeray mein na saah/ pallo ghoda khorey khaa. It means palla is better than halwa, because halwa is devoid of life but palla you can enjoy to your heart’s content,” she says. Sindh’s part-desert landscape gave rise to recipes such as wadi (sand)-di-macchhi with the fish being stuffed with green masala and chillies, wrapped in a roti and roasted in the hot sand, and aanee-ji-bhaji or fish roe curry. Then, of course, there are the famous kok palla, methi palla and seyal machhi recipes. In short, the hilsa is regarded as Sindh’s unofficial regional dish.

As the hilsa travels estuary-wards, the regional romances continue. Swimming up the Narmada to Bharuch, it becomes the chaksi or modar, while the Parsis affectionately call it bhing. Says BJ Maneckshaw, in her book Parsi Food and Drinks and Customs, “The historic town of Bharuch, overlooking the Narmada estuary, has given us wonderful and distinctive seafood. Bhoojelo bharuchi bhing caught in the estuary is a classic! Unfortunately, this prize dish has been forgotten.” The Parsi love for eggs is extended to the bhing or hilsa roe in the palate-tickling gharab-nu-achar.

In Tamil Nadu, the hilsa is ulasa and in Karnataka, paliya. Similarly, in the Godavari delta, it is known as pulasa. Pulasa pulusu is a rich, red, fiery curry slow cooked for four hours with ladies fingers. A popular Andhra saying sums it all up: “It’s worth eating pulasa even by selling the nuptials!”

The hilsa’s journey upstream from the sea from May-June to September-October makes monsoon the best time to have this prized fish. The marriage of salt and sweet water gives it its unique taste. Traditionally, fishing stopped after the Navratras, giving time for the roe discharged at the estuaries to spawn and the fish to grow and swim back to the sea. However, various reasons like overfishing, netting baby fish during the forbidden months and modern barrages damming up the upstream corridors are fast driving the species towards extinction. Commercial establishments, fairs and festivals advertising indiscriminate hilsa jamborees only add to the erosion of this national gourmet heritage. It’s time for responsible fishing and responsible consumption.

Speaking of responsible eating, in pre-Independence Bengal, the delicious hilsa curries at the Goalondo ferry ghat on the Padma river, from where passengers boarded steamers to cross over to the erstwhile East Bengal and beyond, have also become history. The supposed superiority of the Padma hilsa over the Ganga variety was a huge draw.

The story goes that the eating-house owners would panic at the number of fish pieces each customer consumed and would, on the sly, request the boats to sound the hooters early, signalling departure. Unperturbed, customers would say, in between mouthfuls: “Let them go, we’ll get the next boat!”

Well, where conservation of the species is concerned, we seem to have missed the boat. It was, perhaps, a death foretold. Mythology predicts the death of the hilsa by way of Lord Shiva’s curse on Meen Nath, the king of fishes, for eavesdropping on a conversation between him and Parvati. With monsoon mania setting in, unabashed eating is poised to touch orgasmic heights, despite the soaring prices and warning signals. Do some of us dare say: “Not in the mood this season, darling?” n

(Pritha Sen is a Gurgaon-based development consultant.

She enjoys delving into the history of regional cuisines.)

Mood food is what we Indians thrive on. Like the lovers in Kalidas’ Ritusamhara (Garland of Seasons), our love affair with food and the emotions it evokes changes hues with the seasons. Inexplicable gastronomic longings tug at our heartstrings as the skies darken. It’s the epic season of the Meghdootam and the clouds come bearing tidings of hot masala chai and sizzling pakodas.

As the first drops of rain promise to turn into a downpour, I throw a casual question at my young friend Ipshita, a trendy woman of the times: “What do you feel like eating?” “Some sort of a roast with herbed potatoes and wine, with Julio Iglesias playing softly in the background,” she says, and then adds in honest admission: “Or, onion fritters with khichdi and fried ilish (hilsa), with some earthy folk music on the side”. Iglesias, take a back seat, the hilsa is programmed into a Bengali’s DNA.

It’s the time of the ilshey guri, the light drizzle heralding the monsoon when the celebrated hilsa, heavy with roe, starts travelling upstream from the sea. Ipshita’s earthy song could well be – Halka haoway megher chhayay/ Ilshey gurir naachh/ Ilshey gurir nachon dekhey/ Nachchey ilish maachh (To the rhythm of a light breeze and the shadow of clouds/ The raindrops prance/ Seeing this delightful sight/ The hilsa fish dance). I have heard many lyrical descriptions of how, when the first drizzles hit the shimmering dark waters, the silvery hilsa spring out and dance delightfully and that’s when the fishermen net them.

As a newcomer in a Kolkata school, I had an epiphany. As I sat alone in a corner of the classroom during lunch break, I watched in fascination a Sindhi classmate unpacking the hot lunch that had just arrived from home. Tucking her serviette firmly in place, she proceeded to attack a large piece of fried hilsa with a fork and spoon. My first thought was how could a “non-Bengali” eat hilsa and that too with a fork? I waited, in morbid anticipation, for her to choke on the first bone. She calmly proceeded to navigate through it expertly, without offering me a single morsel.

The purpose of this little reminiscence is that Bengal claiming sole custodianship of the delicacy called the hilsa has more to do today with the region being the last remaining bastion of a fast dwindling species, than with any unique culinary tradition. The Bengal ilish-mafia is not to be blamed either because just one boneless smoked hilsa popularised by the British Raj in Bengal put the pressure on its people to take ownership and pour out their obsession to the world. Last year, even before the season started in full earnest, one jamai (son-in-law) in Kolkata created news with a Rs 22,000-hilsa on his plate!

The subcontinental hilsa was the king among fish at one time from the Indus in the west to the Cauvery and Godavari in the south, from the Narmada in middle India to the Mahanadi and Brahmani in the south-east, and the Ganga, Padma and Meghna in the east, into Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Stories abound about how the Mughal emperors waited for the silver and vermillion-tinted beauties, as they entered the estuaries through the Arabian Sea on one side and the Bay of Bengal on the other, and swam up from the Bay of Bengal to Kanpur and Allahabad. Clearly, the hilsa once enjoyed an iconic status across India, which, unfortunately, now has shrunk to perhaps just Bengal, Bangladesh and Burma.

Zinda Pir or Jhuley Lal, the mighty Indus deity, worshipped by both Hindus and Muslims, sits on a lotus and rides atop a Palla, the name for the hilsa in Sindh (now in Pakistan). Says Sindhi food expert Alka Keswani: “The fish was sacred for us and termed ‘Darya ka Phool’ (Flowers of the Ocean). Much like the hilsa swims against the tide, the Sindhis, especially after Partition, hold on to the belief that one can rise above the tide.” Interestingly, legendary playwright Habib Tanvir had once likened his art to the hilsa swimming against turbulent currents.

Keswani talks about Thatta, now in Pakistan, where you would get the best hilsa in the world. “There is a Sindhi saying – Pallo seeray khan bhi bhallo/seeray mein na saah/ pallo ghoda khorey khaa. It means palla is better than halwa, because halwa is devoid of life but palla you can enjoy to your heart’s content,” she says. Sindh’s part-desert landscape gave rise to recipes such as wadi (sand)-di-macchhi with the fish being stuffed with green masala and chillies, wrapped in a roti and roasted in the hot sand, and aanee-ji-bhaji or fish roe curry. Then, of course, there are the famous kok palla, methi palla and seyal machhi recipes. In short, the hilsa is regarded as Sindh’s unofficial regional dish.

As the hilsa travels estuary-wards, the regional romances continue. Swimming up the Narmada to Bharuch, it becomes the chaksi or modar, while the Parsis affectionately call it bhing. Says BJ Maneckshaw, in her book Parsi Food and Drinks and Customs, “The historic town of Bharuch, overlooking the Narmada estuary, has given us wonderful and distinctive seafood. Bhoojelo bharuchi bhing caught in the estuary is a classic! Unfortunately, this prize dish has been forgotten.” The Parsi love for eggs is extended to the bhing or hilsa roe in the palate-tickling gharab-nu-achar.

In Tamil Nadu, the hilsa is ulasa and in Karnataka, paliya. Similarly, in the Godavari delta, it is known as pulasa. Pulasa pulusu is a rich, red, fiery curry slow cooked for four hours with ladies fingers. A popular Andhra saying sums it all up: “It’s worth eating pulasa even by selling the nuptials!”

The hilsa’s journey upstream from the sea from May-June to September-October makes monsoon the best time to have this prized fish. The marriage of salt and sweet water gives it its unique taste. Traditionally, fishing stopped after the Navratras, giving time for the roe discharged at the estuaries to spawn and the fish to grow and swim back to the sea. However, various reasons like overfishing, netting baby fish during the forbidden months and modern barrages damming up the upstream corridors are fast driving the species towards extinction. Commercial establishments, fairs and festivals advertising indiscriminate hilsa jamborees only add to the erosion of this national gourmet heritage. It’s time for responsible fishing and responsible consumption.

Speaking of responsible eating, in pre-Independence Bengal, the delicious hilsa curries at the Goalondo ferry ghat on the Padma river, from where passengers boarded steamers to cross over to the erstwhile East Bengal and beyond, have also become history. The supposed superiority of the Padma hilsa over the Ganga variety was a huge draw.

The story goes that the eating-house owners would panic at the number of fish pieces each customer consumed and would, on the sly, request the boats to sound the hooters early, signalling departure. Unperturbed, customers would say, in between mouthfuls: “Let them go, we’ll get the next boat!”

Well, where conservation of the species is concerned, we seem to have missed the boat. It was, perhaps, a death foretold. Mythology predicts the death of the hilsa by way of Lord Shiva’s curse on Meen Nath, the king of fishes, for eavesdropping on a conversation between him and Parvati. With monsoon mania setting in, unabashed eating is poised to touch orgasmic heights, despite the soaring prices and warning signals. Do some of us dare say: “Not in the mood this season, darling?” n

(Pritha Sen is a Gurgaon-based development consultant.

She enjoys delving into the history of regional cuisines.)