Black-and-white close-up photograph of a piece of wood boldly painted in unmixed solid strokes of black and white in a stylised semblance to “ro” and “tho” from the Bengali syllabary.

Tagore’s Bengali-language initials are worked into this “Ro-Tho” wooden seal, stylistically similar to designs used in traditional Haida carvings. Tagore embellished his manuscripts with such art.

Known mostly for his poetry, Tagore wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore’s prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; he is indeed credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. Such stories mostly borrow from deceptively simple subject matter: commoners. Tagore’s non-fiction grappled with history, linguistics, and spirituality. He wrote autobiographies. His travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including Europe Jatrir Potro (Letters from Europe) and Manusher Dhormo (The Religion of Man). His brief chat with Einstein, “Note on the Nature of Reality”, is included as an appendix to the latter. On the occasion of Tagore’s 150th birthday an anthology (titled Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali) of the total body of his works is currently being published in Bengali in chronological order. This includes all versions of each work and fills about eighty volumes. In 2011, Harvard University Press collaborated with Visva-Bharati University to publish The Essential Tagore, the largest anthology of Tagore’s works available in English; it was edited by Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarthy and marks the 150th anniversary of Tagore’s birth.

Tagore was a prolific composer with 2,230 songs to his credit. His songs are known as rabindrasangit (‘Tagore Song’), which merges fluidly into his literature, most of which-poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike-were lyricised. Influenced by the Thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions. They emulated the tonal colour of classical ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga’s melody and rhythm faithfully; others newly blended elements of different ragas. Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not bhanga gaan, the body of tunes revamped with “fresh value” from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavours “external” to Tagore’s own ancestral culture. Scholars have attempted to gauge the emotive force and range of Hindustani ragas:

“the pathos of the purabi raga reminded Tagore of the evening tears of a lonely widow, while kanara was the confused realisation of a nocturnal wanderer who had lost his way. In Bhupali he seemed to hear a voice in the wind saying ‘stop and come hither’. Paraj conveyed to him the deep slumber that overtook one at night’s end.”

Tagore influenced sitar maestro Vilayat Khan and Sarodiyas Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan. His songs are widely popular and undergird the Bengali ethos to an extent perhaps rivalling Shakespeare’s impact on the English-speaking world. It is said that his songs are the outcome of five centuries of Bengali literary churning and communal yearning. Dhan Gopal Mukerji has said that these songs transcend the mundane to the aesthetic and express all ranges and categories of human emotion. The poet gave voice to all-big or small, rich or poor. The poor Ganges boatman and the rich landlord air their emotions in them. They birthed a distinctive school of music whose practitioners can be fiercely traditional: novel interpretations have drawn severe censure in both West Bengal and Bangladesh.

For Bengalis, the songs’ appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore’s poetry, was such that the Modern Review observed that “there is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath’s songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung … Even illiterate villagers sing his songs”. A. H. Fox Strangways of The Observer introduced non-Bengalis to Rabindrasangit in The Music of Hindostan, calling it a “vehicle of a personality … [that] go behind this or that system of music to that beauty of sound which all systems put out their hands to seize.”

In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the National Anthem of Bangladesh. It was written-ironically-to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: lopping Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a ploy to upend the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in shadhu-bhasha, a Sanskritised register of Bengali, and is the first of five stanzas of a Brahmo hymn that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its National Anthem.

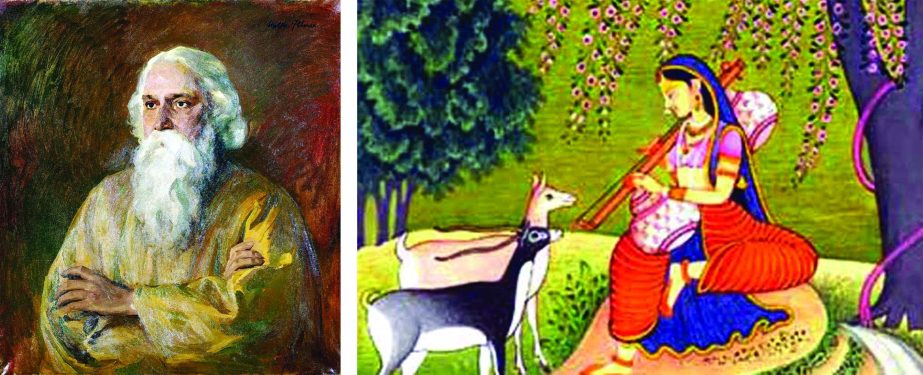

At sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works-which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France-were held throughout Europe. He was likely red-green color blind, resulting in works that exhibited strange colour schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was influenced by scrimshaw from northern New Ireland, Haida carvings from British Columbia, and woodcuts by Max Pechstein. His artist’s eye for his handwriting were revealed in the simple artistic and rhythmic leitmotifs embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts of his manuscripts. Some of Tagore’s lyrics corresponded in a synesthetic sense with particular paintings.

“Surrounded by several painters Rabindranath had always wanted to paint. Writing and music, playwriting and acting came to him naturally and almost without training, as it did to several others in his family, and in even greater measure. But painting eluded him. Yet he tried repeatedly to master the art and there are several references to this in his early letters and reminiscence. In 1900 for instance, when he was nearing forty and already a celebrated writer, he wrote to Jagadishchandra Bose, “You will be surprised to hear that I am sitting with a sketchbook drawing. Needless to say, the pictures are not intended for any salon in Paris, they cause me not the least suspicion that the national gallery of any country will suddenly decide to raise taxes to acquire them. But, just as a mother lavishes most affection on her ugliest son, so I feel secretly drawn to the very skill that comes to me least easily. He also realized that he was using the eraser more than the pencil, and dissatisfied with the results he finally withdrew, deciding it was not for him to become a painter.” -R. Siva Kumar, The Last Harvest : Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore.

Rabindra Chitravali, edited by noted art historian R. Siva Kumar, for the first time makes the paintings of Tagore accessible to art historians and scholars of Rabindranth with critical annotations and comments It also brings together a selection of Rabindranath’s own statements and documents relating to the presentation and reception of his paintings during his lifetime.

The Last Harvest : Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore was an exhibition of Rabindranath Tagore’s paintings to mark the 150th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore. It was commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, India and organised with NGMA Delhi as the nodal agency. It consisted of 208 paintings drawn from the collections of Visva Bharati and the NGMA and presented Tagore’s art in a very comprehensive way. The exhibition was curated by Art Historian R. Siva Kumar. Within the 150th birth anniversary year it was conceived as three separate but similar exhibitions, and travelled simultaneously in three circuits. The first selection was shown at Museum of Asian Art, Berlin, Asia Society, New York, National Museum of Korea, Seoul, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Petit Palais, Paris, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome, National Visual Arts Gallery (Malaysia), Kuala Lumpur, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Ontario, National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

At sixteen, Tagore led his brother Jyotirindranath’s adaptation of Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. At twenty he wrote his first drama-opera: Valmiki Pratibha (The Genius of Valmiki). In it the pandit Valmiki overcomes his sins, is blessed by Saraswati, and compiles the Ramayana. Through it Tagore explores a wide range of dramatic styles and emotions, including usage of revamped kirtans and adaptation of traditional English and Irish folk melodies as drinking songs. Another play, Dak Ghar (The Post Office), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately “falling asleep”, hinting his physical death. A story with borderless appeal-gleaning rave reviews in Europe-Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore’s words, “spiritual freedom” from “the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds”. In the Nazi-besieged Warsaw Ghetto, Polish doctor-educator Janusz Korczak had orphans in his care stage The Post Office in July 1942. In The King of Children, biographer Betty Jean Lifton suspected that Korczak, agonising over whether one should determine when and how to die, was easing the children into accepting death. In mid-October, the Nazis sent them to Treblinka.

“In days long gone by I can see the King’s postman coming down the hillside alone, a lantern in his left hand and on his back a bag of letters climbing down for ever so long, for days and nights, and where at the foot of the mountain the waterfall becomes a stream he takes to the footpath on the bank and walks on through the rye; then comes the sugarcane field and he disappears into the narrow lane cutting through the tall stems of sugarcanes; then he reaches the open meadow where the cricket chirps and where there is not a single man to be seen, only the snipe wagging their tails and poking at the mud with their bills. I can feel him coming nearer and nearer and my heart becomes glad. “-Amal in the Post Office, 1914.

“but the meaning is less intellectual, more emotional and simple. The deliverance sought and won by the dying child is the same deliverance which rose before his imagination, when once in the early dawn he heard, amid the noise of a crowd returning from some festival, this line out of an old village song, “Ferryman, take me to the other shore of the river.” It may come at any moment of life, though the child discovers it in death, for it always comes at the moment when the “I”, seeking no longer for gains that cannot be “assimilated with its spirit”, is able to say, “All my work is thine.” -W. B. Yeats, Preface, The Post Office, 1914.

His other works fuse lyrical flow and emotional rhythm into a tight focus on a core idea, a break from prior Bengali drama. Tagore sought “the play of feeling and not of action”. In 1890 he released what is regarded as his finest drama: Visarjan (Sacrifice). It is an adaptation of Rajarshi, an earlier novella of his. “A forthright denunciation of a meaningless [and] cruel superstitious rite[s] the Bengali originals feature intricate subplots and prolonged monologues that give play to historical events in seventeenth-century Udaipur. The devout Maharaja of Tripura is pitted against the wicked head priest Raghupati. His latter dramas were more philosophical and allegorical in nature; these included Dak Ghar. Another is Tagore’s Chandalika (Untouchable Girl), which was modelled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha’s disciple, asks a tribal girl for water.

In Raktakarabi (“Red” or “Blood Oleanders”), a kleptocrat rules over the residents of Yaksha puri. He and his retainers exploit his subjects-who are benumbed by alcohol and numbered like inventory-by forcing them to mine gold for him. The naive maiden-heroine Nandini rallies her subject-compatriots to defeat the greed of the realm’s sardar class-with the morally roused king’s belated help. Skirting the “good-vs-evil” trope, the work pits a vital and joyous lèse majesté against the monotonous fealty of the king’s varletry, giving rise to an allegorical struggle akin to that found in Animal Farm or Gulliver’s Travels. The original, though prized in Bengal, long failed to spawn a “free and comprehensible” translation, and its archaic and sonorous didacticism failed to attract interest from abroad. Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shyama are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as Rabindra Nritya Natya.

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, among them Chaturanga, Shesher Kobita, Char Odhay, and Noukadubi. Ghare Baire (The Home and the World)-through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil-excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement; a frank expression of Tagore’s conflicted sentiments, it emerged from a 1914 bout of depression. The novel ends in Hindu-Muslim violence and Nikhil’s-likely mortal-wounding.

Gora raises controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity (jati), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle. In it an Irish boy orphaned in the Sepoy Mutiny is raised by Hindus as the titular gora-“whitey”. Ignorant of his foreign origins, he chastises Hindu religious backsliders out of love for the indigenous Indians and solidarity with them against his hegemon-compatriots. He falls for a Brahmo girl, compelling his worried foster father to reveal his lost past and cease his nativist zeal. As a “true dialectic” advancing “arguments for and against strict traditionalism”, it tackles the colonial conundrum by “portray[ing] the value of all positions within a particular frame not only syncretism, not only liberal orthodoxy, but the extremest reactionary traditionalism he defends by an appeal to what humans share.” Among these Tagore highlights “identity conceived of as dharma.”

In Jogajog (Relationships), the heroine Kumudini-bound by the ideals of Siva-Sati, exemplified by Dakshayani-is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil: her roue of a husband. Tagore flaunts his feminist leanings; pathos depicts the plight and ultimate demise of women trapped by pregnancy, duty, and family honour; he simultaneously trucks with Bengal’s putrescent landed gentry. The story revolves around the underlying rivalry between two families-the Chatterjees, aristocrats now on the decline (Biprodas) and the Ghosals (Madhusudan), representing new money and new arrogance. Kumudini, Biprodas’ sister, is caught between the two as she is married off to Madhusudan. She had risen in an observant and sheltered traditional home, as had all her female relations.

Others were uplifting : Shesher Kobita-translated twice as Last Poem and Farewell Song-is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by a poet protagonist. It contains elements of satire and postmodernism and has stock characters who gleefully attack the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by a familiar name: “Rabindranath Tagore”. Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations by Ray and others: Chokher Bali and Ghare Baire are exemplary. In the first, Tagore inscribes Bengali society via its heroine: a rebellious widow who would live for herself alone. He pillories the custom of perpetual mourning on the part of widows, who were not allowed to remarry, who were consigned to seclusion and loneliness. Tagore wrote of it: “I have always regretted the ending”.

Tagore’s three-volume Galpaguchchha comprises eighty-four stories that reflect upon the author’s surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on mind puzzles. Tagore associated his earliest stories, such as those of the “Sadhana” period, with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these traits were cultivated by zamindar Tagore’s life in Patisar, Shajadpur, Shelaidaha, and other villages. Seeing the common and the poor, he examined their lives with a depth and feeling singular in Indian literature up to that point. In “The Fruitseller from Kabul”, Tagore speaks in first person as a town dweller and novelist imputing exotic perquisites to an Afghan seller. He channels the lucubrative lust of those mired in the blasé, nidorous, and sudorific morass of subcontinental city life: for distant vistas. “There were autumn mornings, the time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it I would fall to weaving a network of dreams: the mountains, the glens, the forest .

The Golpoguchchho (Bunch of Stories) was written in Tagore’s Sabuj Patra period, which lasted from 1914 to 1917 and was named for another of his magazines. These yarns are celebrated fare in Bengali fiction and are commonly used as plot fodder by Bengali film and theatre. The Ray film Charulata echoed the controversial Tagore novella Nastanirh (The Broken Nest). In Atithi, which was made into another film, the little Brahmin boy Tarapada shares a boat ride with a village zamindar. The boy relates his flight from home and his subsequent wanderings. Taking pity, the elder adopts him; he fixes the boy to marry his own daughter. The night before his wedding, Tarapada runs off-again. Strir Patra (The Wife’s Letter) is an early treatise in female emancipation. Mrinal is wife to a Bengali middle class man: prissy, preening, and patriarchal. Travelling alone she writes a letter, which comprehends the story. She details the pettiness of a life spent entreating his viraginous virility; she ultimately gives up married life, proclaiming, Amio bachbo. Ei bachlum: “And I shall live. Here, I live.”

Haimanti assails Hindu arranged marriage and spotlights their often dismal domesticity, the hypocrisies plaguing the Indian middle classes, and how Haimanti, a young woman, due to her insufferable sensitivity and free spirit, foredid herself. In the last passage Tagore blasts the reification of Sita’s self-immolation attempt; she had meant to appease her consort Rama’s doubts of her chastity. Musalmani Didi eyes recrudescent Hindu-Muslim tensions and, in many ways, embodies the essence of Tagore’s humanism. The somewhat auto-referential Darpaharan describes a fey young man who harbours literary ambitions. Though he loves his wife, he wishes to stifle her literary career, deeming it unfeminine. In youth Tagore likely agreed with him. Darpaharan depicts the final humbling of the man as he ultimately acknowledges his wife’s talents. As do many other Tagore stories, Jibito o Mrito equips Bengalis with a ubiquitous epigram: Kadombini moriya proman korilo she more nai-“Kadombini died, thereby proving that she hadn’t.”

Tagore’s poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa and other rishi-authors of the Upanishads, the Bhakti-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad Sen. Tagore’s most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul ballads such as those of the bard Lalon. These, rediscovered and repopularised by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kortabhoja hymns that emphasise inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois bhodrolok religious and social orthodoxy. During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the moner manush, the Bauls’ “man within the heart” and Tagore’s “life force of his deep recesses”, or meditating upon the jeebon debota-the demiurge or the “living God within”. This figure connected with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhanusimha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna romance, which were repeatedly revised over the course of seventy years.

“The time that my journey takes is long and the way of it long.

I came out on the chariot of the first gleam of light, and pursued my voyage through the wildernesses of worlds leaving my track on many a star and planet.

It is the most distant course that comes nearest to thyself, and that training is the most intricate which leads to the utter simplicity of a tune.

The traveller has to knock at every alien door to come to his own, and one has to wander through all the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at the end.

My eyes strayed far and wide before I shut them and said ‘Here art thou!’

The question and the cry ‘Oh, where?’ melt into tears of a thousand streams and deluge the world with the flood of the assurance ‘I am!'”- Song XII, Gitanjali, 1913.

Tagore reacted to the halfhearted uptake of modernist and realist techniques in Bengali literature by writing matching experimental works in the 1930s. These include Africa and Camalia, among the better known of his latter poems.

He occasionally wrote poems using Shadhu Bhasha, a Sanskritised dialect of Bengali ; he later adopted a more popular dialect known as Cholti Bhasha. Other works include Manasi, Sonar Tori (Golden Boat), Balaka (Wild Geese, a name redolent of migrating souls), and Purobi. Sonar Tori’s most famous poem, dealing with the fleeting endurance of life and achievement, goes by the same name; hauntingly it ends: Shunno nodir tire rohinu pori/Jaha chhilo loe gêlo shonar tori-“all I had achieved was carried off on the golden boat-only I was left behind.” Gitanjali is Tagore’s best-known collection internationally, earning him his Nobel.

Tagore manuscript c.jpg

Three-verse handwritten composition; each verse has original Bengali with English-language translation below: “My fancies are fireflies: specks of living light twinkling in the dark. The same voice murmurs in these desultory lines, which is born in wayside pansies letting hasty glances pass by. The butterfly does not count years but moments, and therefore has enough time.”

Hungary, 1926.

Tagore’s poetry has been set to music by composers: Arthur Shepherd’s triptych for soprano and string quartet, Alexander Zemlinsky’s famous Lyric Symphony, Josef Bohuslav Foerster’s cycle of love songs, Leos Janacek’s famous chorus “Potulny sílenec” (“The Wandering Madman”) for soprano, tenor, baritone, and male chorus-JW 4/43-inspired by Tagore’s 1922 lecture in Czechoslovakia which Janácek attended, and Garry Schyman’s “Praan”, an adaptation of Tagore’s poem “Stream of Life” from Gitanjali. The latter was composed and recorded with vocals by Palbasha Siddique to accompany Internet celebrity Matt Harding’s 2008 viral video. In 1917 his words were translated adeptly and set to music by Anglo-Dutch composer Richard Hageman to produce a highly regarded art song: “Do Not Go, My Love”. The second movement of Jonathan Harvey’s “One Evening” (1994) sets an excerpt beginning “As I was watching the sunrise …” from a letter of Tagore’s, this composer having previously chosen a text by the poet for his piece “Song Offerings” (1985).

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists, and these views were first revealed in Manast, which was mostly composed in his twenties. Evidence produced during the Hindu-German Conspiracy Trial and latter accounts affirm his awareness of the Ghadarites, and stated that he sought the support of Japanese Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake and former Premier Okuma Shigenobu. Yet he lampooned the Swadeshi movement; he rebuked it in “The Cult of the Charka”, an acrid 1925 essay. He urged the masses to avoid victimology and instead seek self-help and education, and he saw the presence of British administration as a “political symptom of our social disease”. He maintained that, even for those at the extremes of poverty, “there can be no question of blind revolution”; preferable to it was a “steady and purposeful education”.

“So I repeat we never can have a true view of man unless we have a love for him. Civilisation must be judged and prized, not by the amount of power it has developed, but by how much it has evolved and given expression to, by its laws and institutions, the love of humanity.”- Sadhana: The Realisation of Life, 1916.

Such views enraged many. He escaped assassination-and only narrowly-by Indian expatriates during his stay in a San Francisco hotel in late 1916; the plot failed when his would-be assassins fell into argument. Tagore wrote songs lionising the Indian independence movement. Two of Tagore’s more politically charged compositions, ‘Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo’ (‘Where the Mind is Without Fear’) and “Ekla Chalo Re” (“If They Answer Not to Thy Call, Walk Alone”), gained mass appeal, with the latter favoured by Gandhi. Though somewhat critical of Gandhian activism, Tagore was key in resolving a Gandhi-Ambedkar dispute involving separate electorates for untouchables, thereby mooting at least one of Gandhi’s fasts ‘unto death’.

Tagore renounced his knighthood, in response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. In the repudiation letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote

“The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.”

Tagore despised rote classroom schooling: in ‘The Parrot’s Training’, a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages-to death. Tagore, visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, conceived a new type of university: he sought to “make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world [and] a world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography.” The school, which he named Visva-Bharati had its foundation stone laid on 24 December 1918 and was inaugurated precisely three years later. Tagore employed a brahmacharya system: gurus gave pupils personal guidance-emotional, intellectual, and spiritual. Teaching was often done under trees. He staffed the school, he contributed his Nobel Prize monies, and his duties as steward-mentor at Santiniketan kept him busy: mornings he taught classes; afternoons and evenings he wrote the students’ textbooks. He fundraised widely for the school in Europe and the United States between 1919 and 1921.

On 25 March 2004, Tagore’s Nobel Prize was stolen from the safety vault of the Visva-Bharati University, along with several other of his personal belongings. On 7 December 2004, the Swedish Academy decided to present two replicas of Tagore’s Nobel Prize, one made of gold and the other made of bronze, to the Visva Bharati University.

A bronze bust of a middle-aged and forward-gazing bearded man supported on a tall rectangular wooden pedestal above a larger plinth set amidst a small ornate octagonal museum room with pink walls and wooden panelling; flanking the bust on the wall behind are two paintings of Tagore: to the left, a costumed youth acting a drama scene; to the right, a portrait showing an aged man with a large white beard clad in black and red robes.

Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: Kabipranam, his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois; Rabindra Path Parikrama walking pilgrimages from Calcutta to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries. Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen deemed Tagore a “towering figure”, a “deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker”. Tagore’s Bengali originals-the 1939 Rabindra Rachanavali-is canonised as one of his nation’s greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: “the greatest poet India has produced”.

Who are you, reader, reading my poems an hundred years hence?

I cannot send you one single flower from this wealth of the spring, one single streak of gold from yonder clouds.

Open your doors and look abroad.

From your blossoming garden gather fragrant memories of the vanished flowers of an hundred years before.

“In the joy of your heart may you feel the living joy that sang one spring morning, sending its glad voice across an hundred years.”- The Gardener, 1915.

Tagore was renowned throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He co-founded Dartington Hall School, a progressive coeducational institution; in Japan, he influenced such figures as Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata. Tagore’s works were widely translated into English, Dutch, German, Spanish, and other European languages by Czech indologist Vincenc Lesny, French Nobel laureate Andre Gide, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, former Turkish Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, and others. In the United States, Tagore’s lecturing circuits, particularly those of 1916-1917, were widely attended and wildly acclaimed. Some controversies involving Tagore, possibly fictive, trashed his popularity and sales in Japan and North America after the late 1920s, concluding with his “near total eclipse” outside Bengal. Yet a latent reverence of Tagore was discovered by an astonished Salman Rushdie during a trip to Nicaragua.

By way of translations, Tagore influenced Chileans Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral; Mexican writer Octavio Paz; and Spaniards Jose Ortegay Gasset, Zenobia Camprubi, and Juan Ramon Jiménez. In the period 1914-1922, the Jiménez-Camprubi pair produced twenty-two Spanish translations of Tagore’s English corpus; they heavily revised The Crescent Moon and other key titles. In these years, Jimenez developed “naked poetry”. Ortega y Gasset wrote that “Tagore’s wide appeal [owes to how] he speaks of longings for perfection that we all have Tagore awakens a dormant sense of childish wonder, and he saturates the air with all kinds of enchanting promises for the reader, who pays little attention to the deeper import of Oriental mysticism”. Tagore’s works circulated in free editions around 1920-alongside those of Plato, Dante, Cervantes, Goethe, and Tolstoy.

Tagore was deemed over-rated by some. Graham Greene doubted that “anyone but Mr. Yeats can still take his poems very seriously.” Several prominent Western admirers-including Pound and, to a lesser extent, even Yeats-criticised Tagore’s work. Yeats, unimpressed with his English translations, railed against that “Damn Tagore. We got out three good books, Sturge Moore and I, and then, because he thought it more important to know English than to be a great poet, he brought out sentimental rubbish and wrecked his reputation. Tagore does not know English, no Indian knows English.” William Radice, who “Englished” his poems, asked: “What is their place in world literature?” He saw him as “kind of counter-cultural,” bearing “a new kind of classicism” that would heal the “collapsed romantic confusion and chaos of the 20th century.” The translated Tagore was “almost nonsensical”, and subpar English offerings reduced his trans-national appeal:

“anyone who knows Tagore’s poems in their original Bengali cannot feel satisfied with any of the translations (made with or without Yeats’s help). Even the translations of his prose works suffer, to some extent, from distortion. E.M. Forster noted [of] The Home and the World [that] “the theme is so beautiful,” but the charms have “vanished in translation,” or perhaps “in an experiment that has not quite come off.” -Amartya Sen, “Tagore and His India”.

The SNLTR hosts the 1415 BE edition of Tagore’s complete Bengali works. Tagore Web also hosts an edition of Tagore’s works, including annotated songs. Translations are found at Project Gutenberg and Wikisource. More sources are below:

Original

Bengali Poetry

* Bhanusiha Thakurer Paavali (Songs of Bhanusitha Thakur) 1884

* Manasi (The Ideal One) 1890

* Sonar Tari (The Golden Boat) 1894

* Gitanjali (Song Offerings) 1910

* Gitimalya (Wreath of Songs) 1914

* Balaka (The Flight of Cranes) 1916 Dramas

* Valmiki-Pratibha (The Genius of Valmiki) 1881

* Visarjan (The Sacrifice) 1890

* Raja (The King of the Dark Cham