BBC Online :

The 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to a trio of researchers for improving the resolution of optical microscopes.

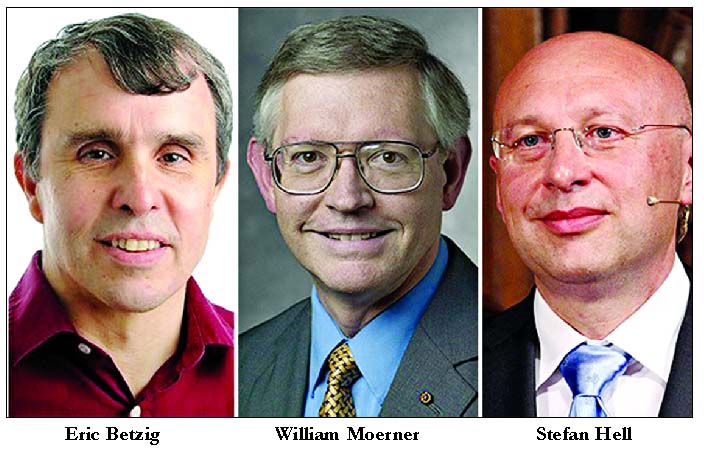

Eric Betzig, Stefan Hell and William Moerner used fluorescence to extend the limits of the light microscope.

The winners will share prize money of eight million kronor (£0.7m).

They were named at a press conference in Sweden, and join a prestigious list of 105 other Chemistry laureates recognised since 1901.

The Nobel Committee said the researchers had won the award for “the

development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy”. Profs Betzig and Moerner are US citizens, while Prof Hell is German.

Committee chair Prof Sven Lidin, a materials chemist from Lunds University, said “the work of the laureates has made it possible to study molecular processes in real time”.

Optical microscopes had previously been held back by a presumed limitation: that they would never obtain a better resolution than half the wavelength of light.

This assumption was based on a rule known as Abbe’s diffraction limit, named after an equation published in 1873 by the German microscopist Ernst Abbe.

This year’s chemistry laureates used fluorescent molecules to circumvent this limitation, allowing scientists to see things at much higher levels of resolution.

Chemistry laureates From left: Eric Betzig, Stefan Hell and William Moerner

Their advance enabled scientists to visualise the activity of individual molecules inside living cells.

Addressing the news conference in Stockholm, Prof Hell, from the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Germany, explained: “I got bored with the topic; I felt this was 19th century physics. I was wondering if there was still something profound that could be made with light microscopy. So I saw that the diffraction barrier was the only important problem that had been left over.

“Eventually I realised there must be a way by playing with the molecules, trying to turn the molecules on and off allows you to see adjacent things you couldn’t see before.”

Bypassing Abbe’s physical limit of 0.2 micrometres means that the optical microscope can now peer into the nanoscopic world.

Commenting on the announcement, Prof Thomas Barton, president of the American Chemical Society, told BBC News: “On my level, the most impressive thing is to look at small molecules, to look at viruses in an atomic-resolved fashion.

“Also… to be able to look at living things and not to have to sacrifice them and look at them in a vacuum after sacrificing them as we do with transmission electron spectroscopy.

“It’s incredible what you can do now. On my timescale, if you had suggested being able to look at something on a one nanometre scale – an atomic scale – 50 years ago, you’d have been laughed out of the room.”

The Royal Society of Chemistry’s president, Prof Dominic Tildesley, commented: “Super-resolution fluorescence spectroscopy is now enabling scientists to peer inside living nerve cells in order to explore brain synapses, study proteins involved in Huntington’s disease and track cell division in embryos – revealing whole new levels of understanding as to what is going on in the human body down to the nanoscale.

He added: “Both involving light and both having their foundations in chemistry and physics, the parallels between today’s Chemistry prize and yesterday’s Physics prize highlight the truly interdisciplinary nature of science.”

The 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to a trio of researchers for improving the resolution of optical microscopes.

Eric Betzig, Stefan Hell and William Moerner used fluorescence to extend the limits of the light microscope.

The winners will share prize money of eight million kronor (£0.7m).

They were named at a press conference in Sweden, and join a prestigious list of 105 other Chemistry laureates recognised since 1901.

The Nobel Committee said the researchers had won the award for “the

development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy”. Profs Betzig and Moerner are US citizens, while Prof Hell is German.

Committee chair Prof Sven Lidin, a materials chemist from Lunds University, said “the work of the laureates has made it possible to study molecular processes in real time”.

Optical microscopes had previously been held back by a presumed limitation: that they would never obtain a better resolution than half the wavelength of light.

This assumption was based on a rule known as Abbe’s diffraction limit, named after an equation published in 1873 by the German microscopist Ernst Abbe.

This year’s chemistry laureates used fluorescent molecules to circumvent this limitation, allowing scientists to see things at much higher levels of resolution.

Chemistry laureates From left: Eric Betzig, Stefan Hell and William Moerner

Their advance enabled scientists to visualise the activity of individual molecules inside living cells.

Addressing the news conference in Stockholm, Prof Hell, from the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Germany, explained: “I got bored with the topic; I felt this was 19th century physics. I was wondering if there was still something profound that could be made with light microscopy. So I saw that the diffraction barrier was the only important problem that had been left over.

“Eventually I realised there must be a way by playing with the molecules, trying to turn the molecules on and off allows you to see adjacent things you couldn’t see before.”

Bypassing Abbe’s physical limit of 0.2 micrometres means that the optical microscope can now peer into the nanoscopic world.

Commenting on the announcement, Prof Thomas Barton, president of the American Chemical Society, told BBC News: “On my level, the most impressive thing is to look at small molecules, to look at viruses in an atomic-resolved fashion.

“Also… to be able to look at living things and not to have to sacrifice them and look at them in a vacuum after sacrificing them as we do with transmission electron spectroscopy.

“It’s incredible what you can do now. On my timescale, if you had suggested being able to look at something on a one nanometre scale – an atomic scale – 50 years ago, you’d have been laughed out of the room.”

The Royal Society of Chemistry’s president, Prof Dominic Tildesley, commented: “Super-resolution fluorescence spectroscopy is now enabling scientists to peer inside living nerve cells in order to explore brain synapses, study proteins involved in Huntington’s disease and track cell division in embryos – revealing whole new levels of understanding as to what is going on in the human body down to the nanoscale.

He added: “Both involving light and both having their foundations in chemistry and physics, the parallels between today’s Chemistry prize and yesterday’s Physics prize highlight the truly interdisciplinary nature of science.”