Walid Khan :

Everything was fine in Greece after restoration of democracy in 1974. People enjoyed high standard of living and very high human development index. Where Tourism, shipping, industrial products (food and tobacco processing), textiles, chemicals, metal product, mining and petroleum Industries moved forward and accelerated the GDP. The inflation rate, budget deficit, public debt, long-term interest rate, exchange rate was also satisfactory. As a result, Greece was accepted into the economic and monetary union of the European union by European council on June 19, 2000.

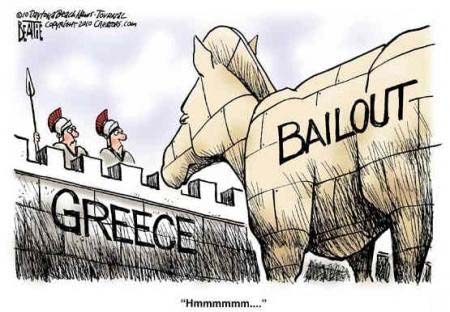

In March 2004, the centre-right government took power. What it discovered was appalling. The budget deficit was not 1.5 per cent, as reported, but 8.3 per cent, which was five and a half times higher than thought. The government faced a dilemma. This economical situation gone worse from late 2009, fear of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors concerning Greece’s ability to meet its debt obligations due to strong increase in government debt levels. On 2nd May 2010, the Eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund agreed on a €110 (at the usurious interest rate of 5 per cent) billion loan for Greece, conditional on the implementation of bailout program. This program came with strict conditions, among them that the government had to improve its tax collection and save money in an effort to bring its budget into balance. Saving government money meant laying off government workers. And that meant those workers had less to spend, so other businesses suffered and laid off workers, too. Unemployment rose, depressing government tax revenues. These have proved extremely unpopular with the Greek public, precipitating demonstrations and civil unrest.

After two years the situation was not improved, the bailout medicine didn’t do the trick. In February 2012, the government accepted another bailout loan, bringing the total borrowed amount to 246 billion Euros. A new austerity plan was agreed upon as well. The amount owed to the international lenders was 135 per cent of the country’s GDP and things were just getting worse. Unemployment rate rose to near 30 per cent. Youth unemployment soared over 50 per cent.

This crisis did not happen overnight, and there’s no single reason. The roots of the crisis run deep with many contributing factors including the highest pension spending, bizarre employment benefit, early retirement policy, tax evasion and high unemployment.

Greece spent 17.5 per cent of its economic output on pension payments, the highest in the EU, according to the most recent Eurostat data from 2012. But with existing cuts this figure has fallen to 16 percent. Italy, France and Austria each spent about 15 per cent of their GDP on pensions in 2012, according to Eurostat. For example a farmer receives 600 euros and a small businessmen receives 700 euro per month after reducing 40 percent compared to what they received five years ago.

Government employees have had some of the best worker benefits in Greece. Like, an unmarried daughter used to receive her dead father’s pension, though that specific practice stopped after the bailout agreement was made in 2010. Some workers received atypical bonuses for showing up to work on time, either way, it’s a practice that austerity measures eliminated.

In 2013, Greece’s retirement age was raised by two years to 67. According to government data, the average Greek man retires at 63 and the average woman at 59. And some police and military workers have retired as early as age 40 or 45. There were also unique benefits for some workers. Female employees of state-owned banks with children under 18 could retire as early at 43.

The country has struggled to collect taxes from citizens, especially the wealthy, which is a problem when Greece’s national debt is 177 per cent of its GDP. Italy’s debt is about 133 per cent of its GDP as of 2014, according to Eurostat.

The Greece episode took a new turn this June, just before default IMF, EU and ECB payment. Greece shut down its banks and limited cash withdrawals to just 60 euros a day, which created financial chaos among its citizens. Whereas Foreigners are reportedly able to withdraw their usual amounts of money as long as they use a foreign bank’s debit or credit card. Drivers are also waiting in long car lines at gas stations, fearing that the country won’t be able to secure its fuel supplies. Tourism is collapsing. Data released by the Travelplanet 24 and Airticket websites show airline bookings have fallen by half. Businesses are reporting that they are unable to process imports or exports, with days of inventory left to fuel production.

Consider all of these conditions; governing Syriza party had campaigned against international bailout program. And reasult was 61.3 per cent voted for ‘No,’ where 38.7 per cent who voted ‘Yes.’

As a result Greece and its European creditors meet in Brussels to decide Greece’s fate. After a long time negotiation they announced an agreement that aims to resolve the country’s debt crisis by keeping Greece in the Eurozone, but that will require further budgetary belt-tightening.

The agreement does not guarantee that Greece will receive its third bailout in five years. But it does allow the start of detailed negotiations on a new assistance package for Greece.

Everything was fine in Greece after restoration of democracy in 1974. People enjoyed high standard of living and very high human development index. Where Tourism, shipping, industrial products (food and tobacco processing), textiles, chemicals, metal product, mining and petroleum Industries moved forward and accelerated the GDP. The inflation rate, budget deficit, public debt, long-term interest rate, exchange rate was also satisfactory. As a result, Greece was accepted into the economic and monetary union of the European union by European council on June 19, 2000.

In March 2004, the centre-right government took power. What it discovered was appalling. The budget deficit was not 1.5 per cent, as reported, but 8.3 per cent, which was five and a half times higher than thought. The government faced a dilemma. This economical situation gone worse from late 2009, fear of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors concerning Greece’s ability to meet its debt obligations due to strong increase in government debt levels. On 2nd May 2010, the Eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund agreed on a €110 (at the usurious interest rate of 5 per cent) billion loan for Greece, conditional on the implementation of bailout program. This program came with strict conditions, among them that the government had to improve its tax collection and save money in an effort to bring its budget into balance. Saving government money meant laying off government workers. And that meant those workers had less to spend, so other businesses suffered and laid off workers, too. Unemployment rose, depressing government tax revenues. These have proved extremely unpopular with the Greek public, precipitating demonstrations and civil unrest.

After two years the situation was not improved, the bailout medicine didn’t do the trick. In February 2012, the government accepted another bailout loan, bringing the total borrowed amount to 246 billion Euros. A new austerity plan was agreed upon as well. The amount owed to the international lenders was 135 per cent of the country’s GDP and things were just getting worse. Unemployment rate rose to near 30 per cent. Youth unemployment soared over 50 per cent.

This crisis did not happen overnight, and there’s no single reason. The roots of the crisis run deep with many contributing factors including the highest pension spending, bizarre employment benefit, early retirement policy, tax evasion and high unemployment.

Greece spent 17.5 per cent of its economic output on pension payments, the highest in the EU, according to the most recent Eurostat data from 2012. But with existing cuts this figure has fallen to 16 percent. Italy, France and Austria each spent about 15 per cent of their GDP on pensions in 2012, according to Eurostat. For example a farmer receives 600 euros and a small businessmen receives 700 euro per month after reducing 40 percent compared to what they received five years ago.

Government employees have had some of the best worker benefits in Greece. Like, an unmarried daughter used to receive her dead father’s pension, though that specific practice stopped after the bailout agreement was made in 2010. Some workers received atypical bonuses for showing up to work on time, either way, it’s a practice that austerity measures eliminated.

In 2013, Greece’s retirement age was raised by two years to 67. According to government data, the average Greek man retires at 63 and the average woman at 59. And some police and military workers have retired as early as age 40 or 45. There were also unique benefits for some workers. Female employees of state-owned banks with children under 18 could retire as early at 43.

The country has struggled to collect taxes from citizens, especially the wealthy, which is a problem when Greece’s national debt is 177 per cent of its GDP. Italy’s debt is about 133 per cent of its GDP as of 2014, according to Eurostat.

The Greece episode took a new turn this June, just before default IMF, EU and ECB payment. Greece shut down its banks and limited cash withdrawals to just 60 euros a day, which created financial chaos among its citizens. Whereas Foreigners are reportedly able to withdraw their usual amounts of money as long as they use a foreign bank’s debit or credit card. Drivers are also waiting in long car lines at gas stations, fearing that the country won’t be able to secure its fuel supplies. Tourism is collapsing. Data released by the Travelplanet 24 and Airticket websites show airline bookings have fallen by half. Businesses are reporting that they are unable to process imports or exports, with days of inventory left to fuel production.

Consider all of these conditions; governing Syriza party had campaigned against international bailout program. And reasult was 61.3 per cent voted for ‘No,’ where 38.7 per cent who voted ‘Yes.’

As a result Greece and its European creditors meet in Brussels to decide Greece’s fate. After a long time negotiation they announced an agreement that aims to resolve the country’s debt crisis by keeping Greece in the Eurozone, but that will require further budgetary belt-tightening.

The agreement does not guarantee that Greece will receive its third bailout in five years. But it does allow the start of detailed negotiations on a new assistance package for Greece.