Yogendra Yadav :

You know what’s afsos mithai?” I did not. But soon it transpired that I did. As a child I called it boodhi amma ke baal. Much later, I would learn the English name for it: candy floss. “For us Kashmiris, Article 370 was like afsos mithai. Lovely appearance, but you regret (afsos) as soon as you find out how little it contains.” I was speaking to Karim (all names changed), this young man in mid-30s with piercing eyes that bore a hole in my skin.

I was in Kashmir for three days, mainly to listen to apple-growers and to assess the damage to their crops. But Kashmiris won’t limit themselves to discussing apples. Not after 5 August this year. Kashmiris have always been very knowledgeable about politics, full of opinions and rich in metaphors. This time, they were more than eager to share their experience of the last 100 days with anyone they could trust. I was all ears.

Using afsos mithai as a metaphor for Article 370 does not mean that ordinary Kashmiris don’t mind its de-facto nullification or that Kashmiris love the post-370 “integration”. Quite the contrary. I did not come across even one coherent voice that supported the central government’s move. Finally, I asked a group of friends if they knew of any Kashmiri living in the Valley who supported the new policy. Pat came the reply, “Koi gadha bhi support nahin karega (Not even a donkey supports this policy)”. They were too sweeping, I thought. I wish I could speak to the few Kashmiri Pandits left in the Valley, but I could not ascertain their views. Our local host was a Pandit but was far too secular and liberal to represent the voice of the community. For the rest, the metaphor of afsos mithai meant that Kashmiris have moved beyond afsos.

No growth, no integration

I did not find any taker for the official rationale that nullification of Article 370 was the harbinger of development in Jammu and Kashmir. We met office-bearers of The Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry to check this. Faheem, a suave, young businessman, summed up an hour-long conversation: “We don’t know whose development is being talked about. There has been a shutdown. We don’t have internet. There is no business. Yet, we are paying salaries to our employees and interest to banks, loan recoveries are going on. Where is the promised investment? We are not a part of any conversation about the economy. I can’t see our economy growing in the next 20 years.”

At least in the first 100 days in the Valley (this reading does not hold for Jammu or Ladakh), the big move on J&K has achieved the opposite of its stated objective.

Far from achieving a closer bond, it has resulted in a deeper, perhaps unbridgeable, emotional chasm. The entire spectrum of public opinion in the Kashmir Valley has been pushed away from India towards Pakistan, from politics of moderation to support for separatism, from Kashmiri identity to stronger Islamic identity. Far from furthering national integration, the new Kashmir doctrine may have caused irreparable damage to India’s national interests.

Middle ground has disappeared

Earlier the public opinion within the Valley ranged between moderates and separatists. Mainstream politicians from the Abdullah family occupied the moderate end that was pro-India. Mehbooba Mufti stood to their right, occasionally airing resentment against the Indian state, but well short of separatism. On the right extreme was the Hurriyat with its pro-Azadi and pro-Pakistan rhetoric.

The most visible effect of 5 August in the Valley is that the spectrum of opinion represented by Abdullahs and Muftis has been wiped out. The afsos articulated by Farooq Abdullah in his tearful appearance on national TV is now looked down upon. ‘Good riddance’ is the general sentiment about most of the mainstream politicians of the Kashmir Valley. Anyone who sets up a relationship with Delhi – someone who contested and won BDC elections, for example – earns the title of a ‘stooge’. Almost overnight, the middle ground – neither separatist nor assimilationist – has disappeared.

People try hard to hide their disenchantment. “Professor sahib, I used to read you and talk to my students about ‘the idea of India’. What should I teach them now?” This was a teacher in a small town. I had no answer.

My old friend Professor Dhar had a wry smile: “We Kashmiris used to joke that these Hindustanis are better than those Khans and Pathans. But now …”. And, after a pause, he looked away and muttered, “I must have been to Delhi dozens of times… This time when I landed there, it felt like a foreign country.”

Amit Shah vs Imran Khan

More than disenchantment, there is a raw anger at what Kashmiris see as an assault on their collective being.

Jameel, a young farmer, stood up in the middle of an involved discussion on the damages to apple-growers: “What has India given us, except dhokha every time?” I thought he was being rhetorical. But Irfan was not. A munshi with an apple trader, he first checked if I would mind him speaking. Once assured, he just folded his hands and said, “Aap hamein chhod kyon nahin dete (Why don’t you leave us alone)?” On being pressed for reasons, he said: “Main apna seena cheer kar kaise dikhaoon ki kitna dard hai (how do I tear my chest apart and show you my pain)?”

This pain has brought the Kashmiri Muslims close to Muslims in the rest of India for the first time. Earlier, their relationship was marked by mutual ignorance, indifference and even contempt. But now the Kashmiri Muslims believe that they are being persecuted not just because they are Kashmiris, but also because they are Muslims.

Kashmiris don’t talk much about Narendra Modi now. Amit Shah is the new face of the Indian state. For many young Kashmiris, the equation is Amit Shah versus Imran Khan. In this face-off, the Pakistani PM has gained in popularity. The video of his UN General Assembly speech with extensive references to Hindutva and Kashmir has gone viral among young Kashmiris. Since there is no internet, it is spreading through pen-drives and Bluetooth.

Kashmiris notice and talk about a contrast between the virtual absence of Kashmiri Muslims from the J&K Raj Bhavan and a generous presence of people with Kashmiri connect in the upper echelons of Pakistani establishment. A college student talked about choosing between India and Pakistan as if he was choosing a holiday destination.

‘The silence spells doom’

Is this pushing the public towards the militants? Hard to say, as I did not enjoy the kind of access needed to answer this question. Over the last three decades, Kashmiris have seen far too much violence to romanticise it. Everyone I spoke to condemn the recent killings of labourers and truck drivers from the rest of India. There were many who advised quiet acceptance of the inevitable. Our driver Akhtar was candid: “What can we Kashmiris do? There are more people in a single district of India than there are in the entire Valley.” But any talk of money fueling militancy or stone-pelting evokes a sharp response: “That’s nonsense. Who would willingly face bullets for any amount of money?” I detected a faint sympathy for the militants but couldn’t be sure.

Karim, who introduced me to afsos mithai, showed me the other end of the spectrum of public opinion in the Valley, his tongue as sharp as his intellect: “5 August has shattered the myth of India’s liberal democracy. People like you may continue to believe that we are opposed to only the BJP regime. The fact is that we are opposed to India. No one cares about 370 or 35A anymore. Now the narrative has shifted from Azadi to Pakistan.”

Then he turned to me: “How do I trust liberals like you? When liberals in the US opposed Vietnam, they refused conscription and paid the price. Pakistani jihadis, who you call terrorists, come here and give up their life for us. How many of you Indian liberals have suffered anything for our sake?” I had no answer.

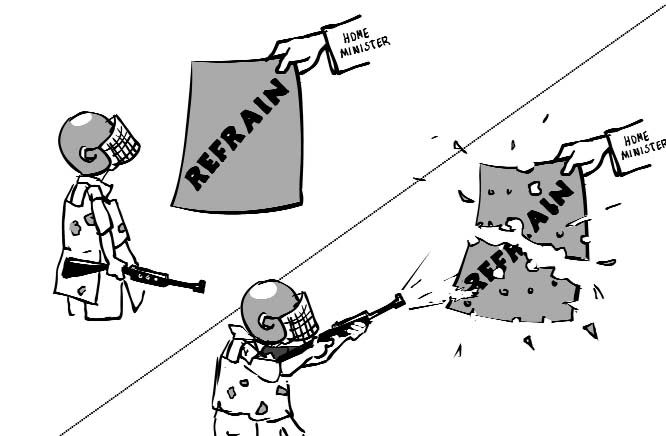

There is a disturbing calm in the Kashmir Valley. Security deployment at every nook and corner has ensured that there is no open protest. There are no leaders on the ground.

Mind is a different field. Kashmiri mind is ticking away furiously. What could be the outcome, I asked another Kashmiri friend. “When there is a death in the family and someone close does not cry, that is a sign of deeper trouble. That is Kashmir after 5 August. If we could cry aloud, protest, things may have come back to some kind of normalcy. But this silence spells doom. Wait till the end of the winter,” he said.

Afsos mithai was long finished. I was holding the stick.

(Yogendra Yadav is the national President of Swaraj India. These are his personal views. He visited Kashmir during 13-15 November with a delegation of All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee. All the names in this article have been changed to protect the identity of the persons concerned.)

You know what’s afsos mithai?” I did not. But soon it transpired that I did. As a child I called it boodhi amma ke baal. Much later, I would learn the English name for it: candy floss. “For us Kashmiris, Article 370 was like afsos mithai. Lovely appearance, but you regret (afsos) as soon as you find out how little it contains.” I was speaking to Karim (all names changed), this young man in mid-30s with piercing eyes that bore a hole in my skin.

I was in Kashmir for three days, mainly to listen to apple-growers and to assess the damage to their crops. But Kashmiris won’t limit themselves to discussing apples. Not after 5 August this year. Kashmiris have always been very knowledgeable about politics, full of opinions and rich in metaphors. This time, they were more than eager to share their experience of the last 100 days with anyone they could trust. I was all ears.

Using afsos mithai as a metaphor for Article 370 does not mean that ordinary Kashmiris don’t mind its de-facto nullification or that Kashmiris love the post-370 “integration”. Quite the contrary. I did not come across even one coherent voice that supported the central government’s move. Finally, I asked a group of friends if they knew of any Kashmiri living in the Valley who supported the new policy. Pat came the reply, “Koi gadha bhi support nahin karega (Not even a donkey supports this policy)”. They were too sweeping, I thought. I wish I could speak to the few Kashmiri Pandits left in the Valley, but I could not ascertain their views. Our local host was a Pandit but was far too secular and liberal to represent the voice of the community. For the rest, the metaphor of afsos mithai meant that Kashmiris have moved beyond afsos.

No growth, no integration

I did not find any taker for the official rationale that nullification of Article 370 was the harbinger of development in Jammu and Kashmir. We met office-bearers of The Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry to check this. Faheem, a suave, young businessman, summed up an hour-long conversation: “We don’t know whose development is being talked about. There has been a shutdown. We don’t have internet. There is no business. Yet, we are paying salaries to our employees and interest to banks, loan recoveries are going on. Where is the promised investment? We are not a part of any conversation about the economy. I can’t see our economy growing in the next 20 years.”

At least in the first 100 days in the Valley (this reading does not hold for Jammu or Ladakh), the big move on J&K has achieved the opposite of its stated objective.

Far from achieving a closer bond, it has resulted in a deeper, perhaps unbridgeable, emotional chasm. The entire spectrum of public opinion in the Kashmir Valley has been pushed away from India towards Pakistan, from politics of moderation to support for separatism, from Kashmiri identity to stronger Islamic identity. Far from furthering national integration, the new Kashmir doctrine may have caused irreparable damage to India’s national interests.

Middle ground has disappeared

Earlier the public opinion within the Valley ranged between moderates and separatists. Mainstream politicians from the Abdullah family occupied the moderate end that was pro-India. Mehbooba Mufti stood to their right, occasionally airing resentment against the Indian state, but well short of separatism. On the right extreme was the Hurriyat with its pro-Azadi and pro-Pakistan rhetoric.

The most visible effect of 5 August in the Valley is that the spectrum of opinion represented by Abdullahs and Muftis has been wiped out. The afsos articulated by Farooq Abdullah in his tearful appearance on national TV is now looked down upon. ‘Good riddance’ is the general sentiment about most of the mainstream politicians of the Kashmir Valley. Anyone who sets up a relationship with Delhi – someone who contested and won BDC elections, for example – earns the title of a ‘stooge’. Almost overnight, the middle ground – neither separatist nor assimilationist – has disappeared.

People try hard to hide their disenchantment. “Professor sahib, I used to read you and talk to my students about ‘the idea of India’. What should I teach them now?” This was a teacher in a small town. I had no answer.

My old friend Professor Dhar had a wry smile: “We Kashmiris used to joke that these Hindustanis are better than those Khans and Pathans. But now …”. And, after a pause, he looked away and muttered, “I must have been to Delhi dozens of times… This time when I landed there, it felt like a foreign country.”

Amit Shah vs Imran Khan

More than disenchantment, there is a raw anger at what Kashmiris see as an assault on their collective being.

Jameel, a young farmer, stood up in the middle of an involved discussion on the damages to apple-growers: “What has India given us, except dhokha every time?” I thought he was being rhetorical. But Irfan was not. A munshi with an apple trader, he first checked if I would mind him speaking. Once assured, he just folded his hands and said, “Aap hamein chhod kyon nahin dete (Why don’t you leave us alone)?” On being pressed for reasons, he said: “Main apna seena cheer kar kaise dikhaoon ki kitna dard hai (how do I tear my chest apart and show you my pain)?”

This pain has brought the Kashmiri Muslims close to Muslims in the rest of India for the first time. Earlier, their relationship was marked by mutual ignorance, indifference and even contempt. But now the Kashmiri Muslims believe that they are being persecuted not just because they are Kashmiris, but also because they are Muslims.

Kashmiris don’t talk much about Narendra Modi now. Amit Shah is the new face of the Indian state. For many young Kashmiris, the equation is Amit Shah versus Imran Khan. In this face-off, the Pakistani PM has gained in popularity. The video of his UN General Assembly speech with extensive references to Hindutva and Kashmir has gone viral among young Kashmiris. Since there is no internet, it is spreading through pen-drives and Bluetooth.

Kashmiris notice and talk about a contrast between the virtual absence of Kashmiri Muslims from the J&K Raj Bhavan and a generous presence of people with Kashmiri connect in the upper echelons of Pakistani establishment. A college student talked about choosing between India and Pakistan as if he was choosing a holiday destination.

‘The silence spells doom’

Is this pushing the public towards the militants? Hard to say, as I did not enjoy the kind of access needed to answer this question. Over the last three decades, Kashmiris have seen far too much violence to romanticise it. Everyone I spoke to condemn the recent killings of labourers and truck drivers from the rest of India. There were many who advised quiet acceptance of the inevitable. Our driver Akhtar was candid: “What can we Kashmiris do? There are more people in a single district of India than there are in the entire Valley.” But any talk of money fueling militancy or stone-pelting evokes a sharp response: “That’s nonsense. Who would willingly face bullets for any amount of money?” I detected a faint sympathy for the militants but couldn’t be sure.

Karim, who introduced me to afsos mithai, showed me the other end of the spectrum of public opinion in the Valley, his tongue as sharp as his intellect: “5 August has shattered the myth of India’s liberal democracy. People like you may continue to believe that we are opposed to only the BJP regime. The fact is that we are opposed to India. No one cares about 370 or 35A anymore. Now the narrative has shifted from Azadi to Pakistan.”

Then he turned to me: “How do I trust liberals like you? When liberals in the US opposed Vietnam, they refused conscription and paid the price. Pakistani jihadis, who you call terrorists, come here and give up their life for us. How many of you Indian liberals have suffered anything for our sake?” I had no answer.

There is a disturbing calm in the Kashmir Valley. Security deployment at every nook and corner has ensured that there is no open protest. There are no leaders on the ground.

Mind is a different field. Kashmiri mind is ticking away furiously. What could be the outcome, I asked another Kashmiri friend. “When there is a death in the family and someone close does not cry, that is a sign of deeper trouble. That is Kashmir after 5 August. If we could cry aloud, protest, things may have come back to some kind of normalcy. But this silence spells doom. Wait till the end of the winter,” he said.

Afsos mithai was long finished. I was holding the stick.

(Yogendra Yadav is the national President of Swaraj India. These are his personal views. He visited Kashmir during 13-15 November with a delegation of All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee. All the names in this article have been changed to protect the identity of the persons concerned.)