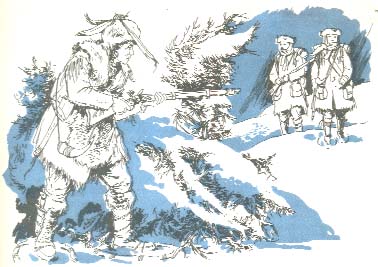

Gilbert Highet :The old gentleman was riding round his land. He had retired several years ago, after a busy career; but farming was what he liked, and he knew that the best way to keep farms prosperous was to supervise them in person. So, although he was approaching seventy, he rode round his property for four or five hours, several days each week. It was not easy for him, but it was not difficult either. He never thought whether a thing was easy or difficult. If it ought to be done, it would be done. Besides, he had always been strong. Although his hair was white and his eyes were dimming, he stood a good six feet and weighed 210 pounds. He rose at four every morning. It was December now, Christmas was approaching, snow was in the air, frost and snow on the ground. This month he had been away from home on a toilsome but necessary trip; and in the hard weather he had been able to ride over his farms very seldom. Still, he liked to see them whenever he could. The land was quiet; yet a deal of work remained to be done. There was much on the old gentleman’s mind. His son had come home from college in some kind of disturbance and uneasiness, unwilling to go back again. Perhaps he should be sent elsewhere-to Harvard, or William and Mary? Perhaps he should have a private tutor? . . . Meanwhile, in order to teach him habits of quiet and undistracted industry, “I can [the old gentleman wrote to a friend], and believe do, keep him in his room a certain portion of the twenty-four hours.” But even so, nothing would substitute for the boy’s own will power, which was apparently defective. The grandchildren, too, were sometimes sick, because they were spoiled. Not by their grandmother, but by their mother. The old gentleman’s wife never spoiled anyone: indeed, she wrote to Fanny to warn her, saying emphatically, “I am sure there is nothing so pernisious as over charging the stomack of a child.” He thought hard and long about the state of the nation. Although he had retired from politics, he was often consulted, and he kept closely in touch. One advantage of retirement was that it gave him time to think over general principles. Never an optimist, he could usually see important dangers some time before they appeared to others. This December, as he rode over the stiff clods under the pale sky, he was thinking over two constant threats to his country. One was the danger of disputes between the separate States and the central government. (Congress had just passed a law designed to combat sedition, and two of the States had immediately denounced it as unconstitutional. This could lead only to disaster.) The other problem was that respectable men were not entering public life. They seemed to prefer to pursue riches, to seek their private happiness, as though such a thing were possible if the nation itself declined. The old gentleman decided to write to Mr. Henry, whom he considered a sound man, and urge him to re-enter politics: he would surely be elected if he would consent to stand; and then, with his experience, he could do much to bridge the gap between the federal government and the States. The old gentleman stopped his, horse. With that large, cool, comprehensive gaze which every visitor always remembered, he looked round the land. It was doing better. Five years ago his farms had been almost ruined by neglect and greed. During his long absence the foremen had cropped them too hard and omitted to cultivate and fertilise, looking for quick and easy profits. Still, even before retiring, he had set about restoring the ground to health and vigour: first, by feeding the soil as much as possible, all year round; second by “a judicious succession of crops”; and third, most important of all, by careful regularity and constant application. As he put it in a letter, “To establish good rules, and a regular system, is the life and the soul of every kind of business.” Now the land was improving every year. It was always a mistake to expect rapid returns. To build up a nation and to make a farm out of the wilderness, both needed long, steady, thoughtful, determined application; both were the work of the will. Long ago, when he was only a boy, he had copied out a set of rules to help in forming his manners and his character-in the same careful way as he would layout a new estate or survey a recently purchased tract of land. The last of the rules he still remembered. Keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called Conscience. Some of the philosophers said that the spark from heaven was reason, the power of the intellect, which we share with God. The old gentleman did not quarrel with them, but he did not believe them. He knew that the divine fire in the spirit was the sense of duty, the lawfulness which orders the whole universe, the power of which a young poet then alive was soon to write :Thou dost preserve the stars from wrong; And the most ancient heavens, through Thee, are fresh and strong, His mind turned back over his long and busy life. He never dreamed or brooded, but he liked to note things down, to plan them and record them. Now, on this cold December day, he could recall nearly every Christmas he had ever spent: sixty at least. Some were peaceful, some were passed in deadly danger, many in war, some in strange lonely places, some in great assemblies, some in happiness and some in anguish of soul, none in despair. One of the worst was Christmas Day of twenty-one years before. That was early in the war, a bad time. It snowed four inches on Christmas. His men were out in the open, with no proper quarters. Although he started them on building shelters, an aggressive move by the enemy made them stand to arms and interrupt all other work for nearly a week. And they had no decent uniforms, no warm coats, no strong shoes, no regular supplies, two days without meat, three days without bread, almost a quarter of his entire force unfit for duty. He was receiving no supplies from the government, and he was actually meeting opposition from the locals. They had sent up a protest against keeping the troops in service during the winter. Apparently they thought you could raise an army whenever you needed one-not understanding that this little force was the only permanent barrier between them and foreign domination. He had replied with crushing energy to that protest. In a letter to the President of Congress, he wrote : I can assure those gentlemen that it is a much easier and less distressing thing to draw remonstrances in a comfortable room by a good fire side than to occupy a cold, bleak hill, and sleep under frost and snow without clothes or blankets. However, although they seem to have little feeling for the naked and distressed soldiers, I feel superabundantly for them, and from my soul I pity those miseries which it is neither in my power to relieve or prevent. He ended with his well-known, strongly and gracefully written signature, G. Washington The year before that, 1776, things had been nearly as bad-the same difficulty about uniforms and supplies. Late in December he wrote earnestly from his camp, “For god sake hurry with the clothing as nothing will contribute more to facilitate the recruiting service than warm and comfortable clothing to those who engage . . . The Commissary informs me that he cannot prevail on the millers to grind; and that the troops in consequence are like to suffer for want of flour . . . This must be remedied by fair or other means.” However, his chief concern then was not supplies, nor discipline, nor defense, but attack. On Christmas Day, long before dawn, he was crossing the Delaware River at McKonkey’s Ferry, with a striking force of over two thousand men. He spent Christmas morning marching to Trenton. Next day he attacked Colonel Rahl and his Hessians. Half of them were sleeping off their Christmas liquor, and nearly all were paralysed with drowsiness and astonishment. Hungry and hopeful, the Americans burst in on them like wolves among fat cattle. The surprise was complete. The victory, prepared on Christmas Day, was the first real success of the war. Two winters later at Christmas time, Washington was in Philadelphia to discuss the plans for next year’s campaign with a Congressional committee. People were very civil; they called him the Cincinnatus of America; and some of them made an effort to take the war seriously. But many did not. He would rather have been in winter quarters with his men. A few days before Christmas 1778 he wrote to Mr. Harrison that, as far as he could see, most people were sunk in “idleness, dissipation, and extravagance … Speculation, peculation, and an insatiable thirst for riches seem to have got the better of every other consideration and almost of every order of men.” Year after year he was in winter quarters at Christmas time, usually in a simple farmhouse, “neither vast nor commodious,” in command of a starving and bankrupt army. In 1781, after York- town, things were a trifle better, and he had dinner with his wife and family at Mr. Morris’s in Philadelphia amid general rejoicing. But the following Christmas was the blackest ever. He had thought of asking for leave, to look after his “long neglected private concerns”; but the army was very close to mutiny, which would have meant the final loss of the war and the probable collapse of the entire nation. It was not only the enlisted men now, it was the officers: they were preparing to make a formal protest to Congress with a list of their grievances; and only the personal influence of Washington himself, only his earnest pleading and his absolute honesty and selflessness, kept the little force in being through that winter. Yet by Christmas the next year, in 1783, it was all over. Washington said farewell to his officers, and then, on December 23rd, he resigned his commission. His formal utterance still stands, grave as a monument : Happy in the confirmation of our Independence and Sovereignty, and pleased with the opportunity afforded the United States of becoming a respectable nation, I resign, with satisfaction, the appointment I accepted with diffidence: a diffidence in my abilities to accomplish so arduous a task, which, however, was superceded by a confidence in the rectitude of our cause the support of the supreme power of the Union, and the patronage of Heaven.So he said. And the President of Congress replied, in terms which, although still balanced and baroque, are more emotional and almost tender : We join you in commending the interests of our dearest country to the Almighty God, beseeching him to dispose the hearts and minds of its citizens, to improve the opportunity afforded them of becoming a happy and respectable nation. And for you, we address to him our earnest prayers, that a life so beloved may be fostered with all his care; that your days may be happy as they have been illustrious; and that he will finally give you that reward which this world cannot give. Next day Washington left for Mount Vernon, and spent Christmas 1783 at home in peace. Some years passed. December was always busy. Washington was on horseback nearly every day, riding round his place, directing the operations which kept the land alive and fed all those who lived on it, ditching, threshing, hog-killing, repairing walls, lifting potatoes, husking corn. And it was a poor December when he did not have at least half a dozen days’ hunting, though in that thickly wooded country he often lost his fox and sometimes hounds too. For Christmas after Christmas in the eighties, his diary shows him living the life of a peaceful squire, and on the day itself usually entertaining friends and relatives. On Christmas Eve 1788, Mr. Madison stayed with him, and was sent on to Colchester next day in Washington’s carriage. Again a change. Christmas 1789 saw him as the first President of the United States, living in New York, the capital of the Union, and receiving formal calls from diplomats and statesmen. In the forenoon he attended St. Paul’s Chapel; in the afternoon Mrs. Washington received visitors, “not numerous, but respectable”; and next day Washington rode out to take his exercise. (He and Theodore Roosevelt were probably the finest horsemen of all our Presidents; those who knew him best liked to think of him on horseback, the most graceful rider in the country.) But for years thereafter his exercise was cut short and his days were swallowed up in the constant crowding of business. (To be continued)He rarely saw his land and seldom visited his home. His Christmases were formal and public; brilliant, but not warm; not holidays. But now, after his final retirement, he had time to look back on earlier Christmases. Some of them were very strange. Christmas of 1751 he had spent at sea. His elder brother Lawrence, frail and overworked, sailed to Barbados for a winter cruise, and George accompanied him. On November 3rd, they landed at Bridgetown, and were invited to dine next day with Major Clarke, O.C. British forces. Washington observed gravely to his diary: ‘We went,-myself with some reluctance, as the smallpox was in his family.” Less than two weeks later Washington was down with smallpox, which kept him in bed for nearly a month; but he recovered with very few marks. By December 25th he and his brother were sailing back, past the Leeward Islands. As he liked to do all through his life, he noted the weather (“fine, clear and pleasant with moderate sea”) and the situation (‘1atitude 18°30”); and, with a youthful exuberance which he soon lost, he adds: “We dined on a fat Irish goose, Beef, &ca &ca, and drank a health to our absent friends.” Five years later, he was a colonel engaged in one of the wars that helped to make this continent Anglo-Saxon instead of Latin: the war to keep the French, pressing downward along the Ohio from Canada and upward along the Mississippi from New Orleans, from encircling the British colonies in an enclave along the coast and cutting them off forever from the wealth of the plains, the rivers, and the distant, fabulous Pacific. Those two Christmases Washington could recall as a time of profound depression, filled with the things he hated most: anarchic competition and anarchic indiscipline. He commanded a Virginia regiment; and Captain Dagworthy of the Maryland troops at Fort Cumberland would not supply him. He despised drunkenness and slack soldiering; and he would not tolerate the attempts by the liquor trade to batten on his troops and run local elections by handing out free liquor. His enemies beat him temporarily, not by bending his will, but by wrecking his health. Christmas 1757 saw him on leave after a physical collapse which looked very like an attack of consumption, involving hemorrhage, fever, and a certain hollowness of the chest which never quite left him. He bore up as well as he could under the barrage of slander which his enemies poured in upon him, including the foulest of all, that he was accepting graft; but he had been ill for months when he finally broke down. (Years later, when he was appointed Commander-in-Chief, he was offered a regular salary, but refused to accept it. Instead, he asked Congress to pay his expenses; he kept the accounts scrupulously; and he presented them without extras at the end of the war. Slanders are always raised about great men; but this one slander was never leveled at Washington again.) He looked back beyond that to one of the hardest Christmases in his memory. That was the Christmas of 1753, when he was only twenty-one. Governor Din- widdie had determined to stop the encirclement of Virginia. The French were building forts on the Ohio, and arresting traders from the British colonies who penetrated that territory. Soon there would be nothing westward except a ring of hostile Indians supported by arrogant French officers. Isolated by land, the colonies could later have been cut off by sea, too, and the seed would have withered almost before it struck firm root. The governor commissioned young Major Washington to make his way to the French fort, to deliver a letter from him to the French commandant, and to bring back both a reply and an estimate of the situation. He did; but he was very nearly killed. Not by the French. Or not directly. They merely told him that they were absolutely determined to take possession of the Ohio territory, and returned a diplomatic but unsatisfactory reply to the governor’s letter.Still, Major Washington had at least the substance of a good intelligence report, for he had inspected the fort and his men had observed how many canoes the French were building. He had only to return. The French, however, endeavoured to persuade him to go up and interview the governor of French Canada; and, that failing, set about bribing the Indians in his party with liquor and guns either to leave him altogether or to delay until the worst of the winter, when travel would be impossible for months. ‘But Washington had a good guide; he was friendly with the Indian chief; and he had a tireless will. He set off on the return journey about the third week in December, when snow was already falling heavily mixed with rain. Six days were spent on a river full of ice. The canoes began to give out. The horses ‘foundered. The rest of the party went more and more slowly. Major Washington “put himself in Indian walking dress” and pushed on, on foot. On Christmas Day he was making his way toward the Great Beaver Creek. Next day he left the entire party to follow with horses, money, and baggage, and set out alone with the guide, Christopher Gist. Next day a lone Indian who pretended to know the territory, but who was evidently a French agent, spent some hours leading the two men off their route, and finally shot at the young officer from close range. Gist would have killed him; but Washington would not allow it: they kept him for several hours, and then let him go. Then they pressed on eastward. They had to cross the swollen, ice-jammed Allegheny River. They built a raft; but they could force it only halfway through the roaring current and the hammering ice blocks. That night they spent freezing on an island in midstream. In the morning, they struggled across on the ice, and pressed on again. In his journal the guide recorded that the major was “much fatigued.” But still he kept going: eighteen miles a day with a gun and a full pack, over rough territory, threatened by hostile Indians, in mid-December, with snow and rain falling from the sky and lying thick on the ground. Now, over a period of forty-five years, he looked back on that Christmas. It had been, he remembered, “as fatiguing a journey as it is possible to conceive”and still a necessary one. It was the first of his many services to his country, to keep it from being surrounded and strangled from without or poisoned from within. And he reflected that it is not necessary to try to be brave, or clever, or generous, or beloved, or even happy. It is necessary simply to do one’s duty. All else Hows from that. Without that, all else is useless. Darkness closed in early in these winter days. It was getting toward Christmas of the year 1798. General Charles Pinckney and his lady were expected for Christmas dinner. The old gentleman finished looking over the land, and turned homeward. He paid no heed to the cold….This tribute to a famous American by a 20th-century, Scottish-born American brings ‘The Old Gentleman’ warmly and vividly to life. The selection is taken from Gilbert Highet’s volume of essays People, Places, and Books. -Types of Literature