Bijoy Venugopal :

Islands top my bucket list. Remote ocean islands, cut away from the mainland for millennia, unique ecosystems with extraordinary plants and animals: Charles Darwin unwrapped the peculiar natural history of the Galapagos; Socotra, 340 km off the coast of Yemen, harbours otherworldly Dragon trees; Australia’s egg-laying mammals are as intriguing as New Zealand’s flightless parrots; and a far-flung Indonesian island produced a gigantic flesh-eating lizard – the Komodo Dragon.

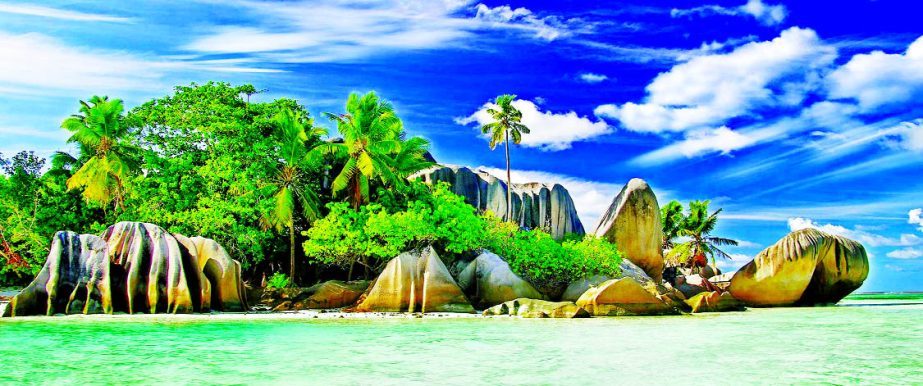

The Seychelles, whose 115 islands lie scattered in the Indian Ocean, 1,600 km east of mainland Africa, possessed my childhood imagination after I chanced upon a clothbound Life photobook in my school library. I read of coral atolls inhabited by elderly giant tortoises, of explorers who snorkelled with dolphins and turtles, gigantic coconuts and ‘The Widow,’ a mysterious black bird that sat mournfully on its nest. Fact and imagination made love and spawned fantasy after fantasy about the Seychelles.

But it would be three decades until I could finally separate fable from fact. My job as travel editor with an internet portal was under threat as the company was downsizing, but I threw caution to the winds. Drifting towards Africa aboard the Air Seychelles red-eye from Mumbai, I watched dawn break over the ocean. Soon, the jade-green hilltops of Mahe, the largest island in the Seychelles, poked their sleepy crowns out of the clouds.

Victoria, the capital city, was more upscale than I had imagined, with an international airport and tony residential neighbourhoods. Behind Victoria, the hills of Morne Seychellois National Park, cloaked in verdant cloud forests interspersed with plantation villas and tea gardens, rise to 900m. In less than 40 minutes, we drove from coast to coast through breathtaking scenery and descended from foggy heights to sunny, postcard-perfect beaches.

Vasco da Gama, en route to India in 1502, observed a cluster of coral islands he named (after himself) as the Amirantes – the Admiral’s Islands. However, the Seychelles were not permanently settled until 1770 when the French established a colony on Mahe. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1814, the Seychelles ceded to the British, who administered it until 1976, when the islands became independent.

In the 17th century, the islands were the playground of pirates. The most celebrated of them was a Frenchman, Olivier Levasseur, nicknamed La Buse (The Buzzard) for his stealth and swiftness. La Buse led a picturesque life until his luck ran out and he was captured and executed.

Moments before the noose tightened, he flung into the crowd a necklace bearing a seven-line cryptogram, claiming that it held clues to the location of his hidden treasure. The cipher has never been cracked entirely. Governments, navies and bounty hunters are still on the hunt for the cache, valued at over a billion dollars.

There are no terrestrial mammals native to the Seychelles, except for bats. One species – the Seychelles fruit bat – is numerous enough for locals to eat. At La Plaine St Andre, a restaurant housed in a distillery that produces the sought-after Takamaka Bay rum, I ordered delicious fruit bat ravioli. The meat was sparse, dark and bony, with a flavour somewhere between tuna and beef.

Despite such creature comforts, I longed to see the birds and trees that had enthralled my boyhood. In Mahe, I met the common Seychelles Blue Pigeon, Seychelles Sunbird and the Seychelles Bulbul. To find the rare Seychelles Black Parrot and uncover the mystery of The Widow, I had to island-hop. Travelling between islands isn’t cheap, but the high-speed catamaran ferries that link Mahe with nearby Praslin and La Digue, are comfortable and convenient.

On La Digue, I cracked the mystery of ‘The Widow’ – the male Seychelles black paradise flycatcher, resplendent in mourning black, had earned itself the unfortunate moniker of La Veuve, French for widow. Fewer than 200 such birds survive on the small island now. On Praslin, the second-largest island, I visited the Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve, a Unesco World Heritage Site. This benign forest shelters an endangered palm that produces the 20-kg Coco de Mer, the world’s largest fruit. Its shape, reminiscent of the female pelvis, is (pun intended) the butt of dirty jokes. The Seychellois, though, celebrate it as a symbol of fertility.

Geckos ran up the palm and a trio of sooty-grey birds alighted on the crown to feed on the flowers. ‘Black parrot,’ our guide exclaimed, “You’re in luck!” Standing there, my dreams began to come true. I was looking at the national bird of the Seychelles, on its national tree, cradling in my arms for a photo-op its national symbol – the fruit of the Coco de Mer.

Giddy with excitement, I returned to the hotel to find an urgent message from work: I had lost my job. Wading into the comforting waves of the Indian Ocean, I relaxed. I felt unyoked, unburdened. In this tranquil Eden, I had found something else, something more precious than La Buse’s treasure. n

Islands top my bucket list. Remote ocean islands, cut away from the mainland for millennia, unique ecosystems with extraordinary plants and animals: Charles Darwin unwrapped the peculiar natural history of the Galapagos; Socotra, 340 km off the coast of Yemen, harbours otherworldly Dragon trees; Australia’s egg-laying mammals are as intriguing as New Zealand’s flightless parrots; and a far-flung Indonesian island produced a gigantic flesh-eating lizard – the Komodo Dragon.

The Seychelles, whose 115 islands lie scattered in the Indian Ocean, 1,600 km east of mainland Africa, possessed my childhood imagination after I chanced upon a clothbound Life photobook in my school library. I read of coral atolls inhabited by elderly giant tortoises, of explorers who snorkelled with dolphins and turtles, gigantic coconuts and ‘The Widow,’ a mysterious black bird that sat mournfully on its nest. Fact and imagination made love and spawned fantasy after fantasy about the Seychelles.

But it would be three decades until I could finally separate fable from fact. My job as travel editor with an internet portal was under threat as the company was downsizing, but I threw caution to the winds. Drifting towards Africa aboard the Air Seychelles red-eye from Mumbai, I watched dawn break over the ocean. Soon, the jade-green hilltops of Mahe, the largest island in the Seychelles, poked their sleepy crowns out of the clouds.

Victoria, the capital city, was more upscale than I had imagined, with an international airport and tony residential neighbourhoods. Behind Victoria, the hills of Morne Seychellois National Park, cloaked in verdant cloud forests interspersed with plantation villas and tea gardens, rise to 900m. In less than 40 minutes, we drove from coast to coast through breathtaking scenery and descended from foggy heights to sunny, postcard-perfect beaches.

Vasco da Gama, en route to India in 1502, observed a cluster of coral islands he named (after himself) as the Amirantes – the Admiral’s Islands. However, the Seychelles were not permanently settled until 1770 when the French established a colony on Mahe. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1814, the Seychelles ceded to the British, who administered it until 1976, when the islands became independent.

In the 17th century, the islands were the playground of pirates. The most celebrated of them was a Frenchman, Olivier Levasseur, nicknamed La Buse (The Buzzard) for his stealth and swiftness. La Buse led a picturesque life until his luck ran out and he was captured and executed.

Moments before the noose tightened, he flung into the crowd a necklace bearing a seven-line cryptogram, claiming that it held clues to the location of his hidden treasure. The cipher has never been cracked entirely. Governments, navies and bounty hunters are still on the hunt for the cache, valued at over a billion dollars.

There are no terrestrial mammals native to the Seychelles, except for bats. One species – the Seychelles fruit bat – is numerous enough for locals to eat. At La Plaine St Andre, a restaurant housed in a distillery that produces the sought-after Takamaka Bay rum, I ordered delicious fruit bat ravioli. The meat was sparse, dark and bony, with a flavour somewhere between tuna and beef.

Despite such creature comforts, I longed to see the birds and trees that had enthralled my boyhood. In Mahe, I met the common Seychelles Blue Pigeon, Seychelles Sunbird and the Seychelles Bulbul. To find the rare Seychelles Black Parrot and uncover the mystery of The Widow, I had to island-hop. Travelling between islands isn’t cheap, but the high-speed catamaran ferries that link Mahe with nearby Praslin and La Digue, are comfortable and convenient.

On La Digue, I cracked the mystery of ‘The Widow’ – the male Seychelles black paradise flycatcher, resplendent in mourning black, had earned itself the unfortunate moniker of La Veuve, French for widow. Fewer than 200 such birds survive on the small island now. On Praslin, the second-largest island, I visited the Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve, a Unesco World Heritage Site. This benign forest shelters an endangered palm that produces the 20-kg Coco de Mer, the world’s largest fruit. Its shape, reminiscent of the female pelvis, is (pun intended) the butt of dirty jokes. The Seychellois, though, celebrate it as a symbol of fertility.

Geckos ran up the palm and a trio of sooty-grey birds alighted on the crown to feed on the flowers. ‘Black parrot,’ our guide exclaimed, “You’re in luck!” Standing there, my dreams began to come true. I was looking at the national bird of the Seychelles, on its national tree, cradling in my arms for a photo-op its national symbol – the fruit of the Coco de Mer.

Giddy with excitement, I returned to the hotel to find an urgent message from work: I had lost my job. Wading into the comforting waves of the Indian Ocean, I relaxed. I felt unyoked, unburdened. In this tranquil Eden, I had found something else, something more precious than La Buse’s treasure. n