Pythia Peay :

In the summer of 1969 I had just graduated from high school. Distressed by my TWA pilot father’s worsening alcoholism, I’d been sent away to live with my Uncle Paul, Joe’s older-and more stable-brother. In this excerpt from my memoir, “American Icarus: A Memoir of Father and Country,” I recount my memory of that historic moment, how it affected me personally-and how it upended the once-secure belief systems of those around me.

By the time my high school graduation came around, I’d begun to come apart from the tensions at home. Even my newly awakened interest in mysticism couldn’t protect me from the stress eating away at my family. At school, I brimmed and nearly burst with creative energy and fiery political rhetoric, wearing down teachers and classmates alike. I talked friends into making regular visits to a juvenile detention home, and prodded my English teacher Miss Miller into putting on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, [my high school] Oak Grove’s first production of a Shakespeare play.

But at home I wore an expression of brooding anger-much like my mother. Looking back, I see that I followed in her emotional footsteps, mirroring her fury against my father. She, in turn, accused Joe of pushing me to the brink of a breakdown with his drinking. Due to my shaky state of mind, it was decided that I should be sent away to Tallahassee, Florida, for the summer. There I could be taken care of by my Uncle Paul, Aunt Ann, and my younger cousin Sharon.

Entering the normalcy of my Uncle Paul’s house was the emotional equivalent of wandering into a safe haven after living on the streets. The warmth of the Florida sun, my aunt’s soothing habit of watching soap operas during the day, and Sharon’s sweet adoration was a salve to my raw feelings. The notion that a family could live such an ordinary life, uninterrupted by hot scenes and chill silences, was a new experience for me. Uncle Paul had stopped drinking years ago. He was worried about my father, he told me, but there was nothing he could do about it. He encouraged me not to think so much about the problems at home and to focus on the future. I got a job as a waitress at a fast food restaurant, and on my off hours I read the latest counter-culture book, Stranger in a Strange Land, by Robert Heinlein.

On July 16th, 1969, Apollo 11 blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center, headed for humankind’s first moon landing. As the daughter of an airman and a child of the space age, I vibrated from head to foot with a champagne fizz of anticipation. Others, however, were less sure about the notion of humans leaving Earth to walk on the moon. Days before touchdown, some people’s long-held belief systems had begun to quake. Aunt Ann was a devout Catholic of firm but simple religious beliefs. To this point, she’d believed that heaven was high over her head and that hell was below, beneath her feet. Now Apollo 11 was, literally, turning her world upside down.

“But in outer space, where the astronauts are going, there is no up and there is no down,” Aunt Ann said, in great puzzlement. “So where are heaven and hell now? Where will I go when I die? Where will I go?” she asked anxiously, deeply perplexed. At the restaurant where I worked, a five-foot-tall, born-again spitfire of a waitress named Dolly held us all spellbound with her fierce denunciations of space travel. NASA was breaking biblical law, she loudly asserted, raising her fist in the air. The crew would never make it to the moon, said Dolly, preaching to her fellow waitresses with absolute conviction. For God would reach out his mighty arm and smite the evil spacecraft from the sky, turning it to cinders and ashes.

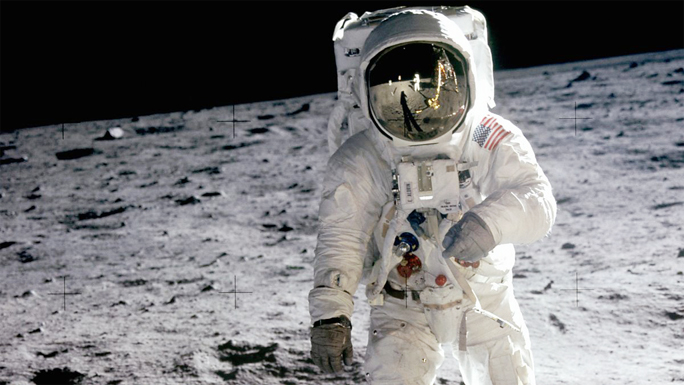

On the evening of the moon landing, I gathered before the television set with Sharon, my aunt, and my uncle. Untroubled by any of the fears shared by Aunt Ann and Dolly the waitress, I could hardly contain myself. When the first fuzzy black-and-white images began to emerge on the screen, the four of us went still. Staring intently, we strained to make out the dim shape of the bulky figure of Neil Armstrong as he descended the lunar module’s ladder. When his foot touched the soft powder of the moon, my spirit took off. We all let out a cheer.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, I felt a stab of homesickness. I knew my family would be watching, and I missed them. The sky and the space beyond it were, after all, my Icarus family’s myth. Something in my face must have given me away. When regular programming resumed, Uncle Paul asked me if I’d like to call my parents. “Hey, Pell,’ wasn’t that something?” said my father when he picked up on the other end. I felt tears sting my eyelids. It was time to go home.

Pythia Peay is also the author of America on the Couch: Psychological Perspectives on American Politics and Beliefs, a collection of interviews with 40 of the world’s leading psychologists and psychoanalysts.

In the summer of 1969 I had just graduated from high school. Distressed by my TWA pilot father’s worsening alcoholism, I’d been sent away to live with my Uncle Paul, Joe’s older-and more stable-brother. In this excerpt from my memoir, “American Icarus: A Memoir of Father and Country,” I recount my memory of that historic moment, how it affected me personally-and how it upended the once-secure belief systems of those around me.

By the time my high school graduation came around, I’d begun to come apart from the tensions at home. Even my newly awakened interest in mysticism couldn’t protect me from the stress eating away at my family. At school, I brimmed and nearly burst with creative energy and fiery political rhetoric, wearing down teachers and classmates alike. I talked friends into making regular visits to a juvenile detention home, and prodded my English teacher Miss Miller into putting on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, [my high school] Oak Grove’s first production of a Shakespeare play.

But at home I wore an expression of brooding anger-much like my mother. Looking back, I see that I followed in her emotional footsteps, mirroring her fury against my father. She, in turn, accused Joe of pushing me to the brink of a breakdown with his drinking. Due to my shaky state of mind, it was decided that I should be sent away to Tallahassee, Florida, for the summer. There I could be taken care of by my Uncle Paul, Aunt Ann, and my younger cousin Sharon.

Entering the normalcy of my Uncle Paul’s house was the emotional equivalent of wandering into a safe haven after living on the streets. The warmth of the Florida sun, my aunt’s soothing habit of watching soap operas during the day, and Sharon’s sweet adoration was a salve to my raw feelings. The notion that a family could live such an ordinary life, uninterrupted by hot scenes and chill silences, was a new experience for me. Uncle Paul had stopped drinking years ago. He was worried about my father, he told me, but there was nothing he could do about it. He encouraged me not to think so much about the problems at home and to focus on the future. I got a job as a waitress at a fast food restaurant, and on my off hours I read the latest counter-culture book, Stranger in a Strange Land, by Robert Heinlein.

On July 16th, 1969, Apollo 11 blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center, headed for humankind’s first moon landing. As the daughter of an airman and a child of the space age, I vibrated from head to foot with a champagne fizz of anticipation. Others, however, were less sure about the notion of humans leaving Earth to walk on the moon. Days before touchdown, some people’s long-held belief systems had begun to quake. Aunt Ann was a devout Catholic of firm but simple religious beliefs. To this point, she’d believed that heaven was high over her head and that hell was below, beneath her feet. Now Apollo 11 was, literally, turning her world upside down.

“But in outer space, where the astronauts are going, there is no up and there is no down,” Aunt Ann said, in great puzzlement. “So where are heaven and hell now? Where will I go when I die? Where will I go?” she asked anxiously, deeply perplexed. At the restaurant where I worked, a five-foot-tall, born-again spitfire of a waitress named Dolly held us all spellbound with her fierce denunciations of space travel. NASA was breaking biblical law, she loudly asserted, raising her fist in the air. The crew would never make it to the moon, said Dolly, preaching to her fellow waitresses with absolute conviction. For God would reach out his mighty arm and smite the evil spacecraft from the sky, turning it to cinders and ashes.

On the evening of the moon landing, I gathered before the television set with Sharon, my aunt, and my uncle. Untroubled by any of the fears shared by Aunt Ann and Dolly the waitress, I could hardly contain myself. When the first fuzzy black-and-white images began to emerge on the screen, the four of us went still. Staring intently, we strained to make out the dim shape of the bulky figure of Neil Armstrong as he descended the lunar module’s ladder. When his foot touched the soft powder of the moon, my spirit took off. We all let out a cheer.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, I felt a stab of homesickness. I knew my family would be watching, and I missed them. The sky and the space beyond it were, after all, my Icarus family’s myth. Something in my face must have given me away. When regular programming resumed, Uncle Paul asked me if I’d like to call my parents. “Hey, Pell,’ wasn’t that something?” said my father when he picked up on the other end. I felt tears sting my eyelids. It was time to go home.

Pythia Peay is also the author of America on the Couch: Psychological Perspectives on American Politics and Beliefs, a collection of interviews with 40 of the world’s leading psychologists and psychoanalysts.

(Pythia Peay is a journalist, who writes about psychology, spirituality and the American psyche. She is the author of American Icarus: A Memoir of Father and Country).