Julia Gillard :

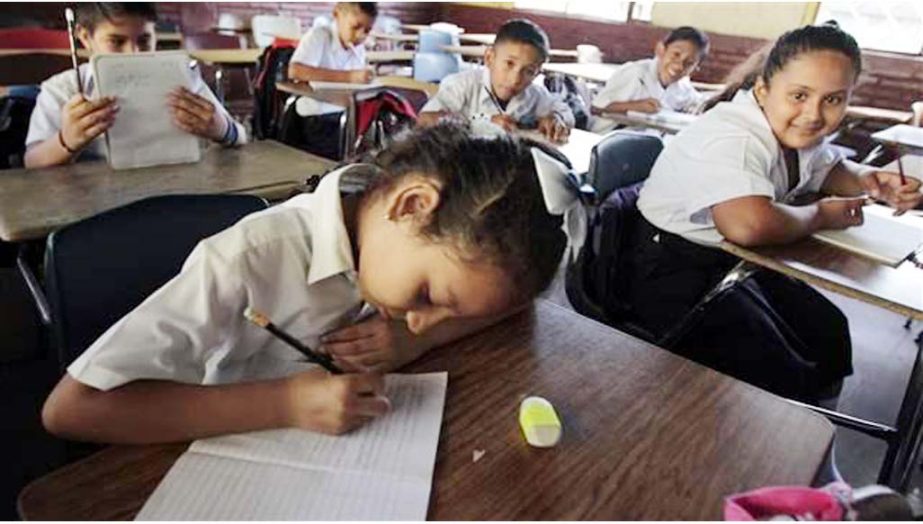

2015 is a year of decision for global education – specifically, access to quality education by children in the world’s poorest and most conflict-ravaged countries. Fifteen years ago, at the United Nations, the world came together to establish the Millennium Development Goal of all children having access to primary school – by this year, 2015.

Enormous strides have been made. Since 1999, 48 million more children have been able to go to primary school. And more children are getting to go to secondary school. The number of children not enrolled in primary or lower secondary dropped from 204 million to 121 million.

However, despite progress in getting more children into school and learning we have not closed the gap. 58 million children of primary school age remain out of school. And 250 million more children are in school but don’t receive any meaningful education. The education glass is half full.

This September, the nations of the world will gather again at the United Nations. One of the sustainable development goals to be adopted will call for access to quality education for all young people through to lower secondary school.

The words are noble, the ambition is audacious indeed. But these words will ring hollow if there are not the resources committed to acquit the goals that are being set. And according to UNESCO, we are at least $22 billion short – annually – in providing what is needed to educate the world’s children.

It is a privilege to write for DFID on these matters. The British government and the British people – acting through DFID and its overseas development assistance programs – are among the most vigorous champions in the world for the global education agenda.

The UK is a leading member of the unique partnership I chair – the Global Partnership for Education. DFID is an active member on the GPE Board of Directors, and we also work closely with DFID in many of the GPE partner countries.

For example, in Tanzania, where DFID and the Global Partnership are involved in teacher training to improve literacy acquisition of primary school students. Or in Zimbabwe where along with other partners we work with the government to strengthen the education system through a set of complementary programs. Also, DFID and the Global Partnership both emphasize the importance of data driven, long-term education plans as a pre-requisite to attain an expansion of and quality in the basic education sector

Since 2002, the Global Partnership has allocated $US 4.3 billion to developing country partners and programs. We are now the largest international funder of basic education in GPE partner countries; in 2014, half of our funding supported fragile and conflict-affected partner countries.

But the Global Partnership for Education is so much more than a global fund. It is a unique partnership model that has been praised by the United Nations as the development model of the future. Both around our board table and within our sixty partner developing countries, the Global Partnership brings together donors, governments, teacher organizations, civil society, the private sector and multilateral organizations in a practical expression of partnership.

That partnership makes this a genuine joint endeavour to finance education for all. At the pledging conference of the Global Partnership last June, while donor governments pledged $2.1 billion for these programs, developing countries pledged to increase their education budgets by a collective US$26 billion.

In a world of economic challenge and geostrategic disorder, we cannot have a more potent weapon in our arsenal than education. Education is the key to a society’s economic development, growth, innovation, dynamism and prosperity. In May, the World Education Forum was held in the Republic of Korea – a magnificent example of the power of education transform a country ravaged by war and poverty and turn it into an economic powerhouse.

But education must be for all of us. If you educate a girl, you change her country. If you change her country, you can change the world. Terrorism – such as Boko Haram, and the men who shot Malala – engages in such atrocities precisely because they know what the power of educating a girl means for truly transforming the world. With equal urgency, we need to implement more effective programs to ensure that children who are deprived of their education by war, famine, natural disasters and epidemics can be given access to education should they be displaced or made refugees.

We can no longer let a child of 5 become an adolescent at 15 – with their education on hold since childhood in a void of a life disrupted by cruel events beyond their control. Gordon Brown, former prime minister of the UK and now the UN Special Envoy for Education, has been leading this effort with urgency and passion – and we at GPE are working closely with him to step up and address this chronic problem.

Education is about learning, and learning is about choices. And we have a choice, as a world community, this year, in 2015:

Will we simply say the good words, and pledge fidelity to their fulfilment when the world’s leaders gather in New York in September?

Or will we, as leaders in global education meeting in Oslo next month, begin to unlock the financing solutions to what is needed?

And will we make the real and meaningful commitments – just as the UK government has through DFID – to guarantee the resources required to make transforming improvements in the future of our children – the poorest, the most marginalised, those fleeing catastrophe, those who instinctively want to grasp a better future.

Throughout this year, I have felt a strong and growing sense of convergence and consensus among those most committed to these goals – that this is the time, this is our fight, this is our commitment. There is a rising tide of optimism on this fundamental quest for quality education for all in order to forge a better world.

And we will succeed.

(Julia Rigard is the former Prime Minister of Australia.)

2015 is a year of decision for global education – specifically, access to quality education by children in the world’s poorest and most conflict-ravaged countries. Fifteen years ago, at the United Nations, the world came together to establish the Millennium Development Goal of all children having access to primary school – by this year, 2015.

Enormous strides have been made. Since 1999, 48 million more children have been able to go to primary school. And more children are getting to go to secondary school. The number of children not enrolled in primary or lower secondary dropped from 204 million to 121 million.

However, despite progress in getting more children into school and learning we have not closed the gap. 58 million children of primary school age remain out of school. And 250 million more children are in school but don’t receive any meaningful education. The education glass is half full.

This September, the nations of the world will gather again at the United Nations. One of the sustainable development goals to be adopted will call for access to quality education for all young people through to lower secondary school.

The words are noble, the ambition is audacious indeed. But these words will ring hollow if there are not the resources committed to acquit the goals that are being set. And according to UNESCO, we are at least $22 billion short – annually – in providing what is needed to educate the world’s children.

It is a privilege to write for DFID on these matters. The British government and the British people – acting through DFID and its overseas development assistance programs – are among the most vigorous champions in the world for the global education agenda.

The UK is a leading member of the unique partnership I chair – the Global Partnership for Education. DFID is an active member on the GPE Board of Directors, and we also work closely with DFID in many of the GPE partner countries.

For example, in Tanzania, where DFID and the Global Partnership are involved in teacher training to improve literacy acquisition of primary school students. Or in Zimbabwe where along with other partners we work with the government to strengthen the education system through a set of complementary programs. Also, DFID and the Global Partnership both emphasize the importance of data driven, long-term education plans as a pre-requisite to attain an expansion of and quality in the basic education sector

Since 2002, the Global Partnership has allocated $US 4.3 billion to developing country partners and programs. We are now the largest international funder of basic education in GPE partner countries; in 2014, half of our funding supported fragile and conflict-affected partner countries.

But the Global Partnership for Education is so much more than a global fund. It is a unique partnership model that has been praised by the United Nations as the development model of the future. Both around our board table and within our sixty partner developing countries, the Global Partnership brings together donors, governments, teacher organizations, civil society, the private sector and multilateral organizations in a practical expression of partnership.

That partnership makes this a genuine joint endeavour to finance education for all. At the pledging conference of the Global Partnership last June, while donor governments pledged $2.1 billion for these programs, developing countries pledged to increase their education budgets by a collective US$26 billion.

In a world of economic challenge and geostrategic disorder, we cannot have a more potent weapon in our arsenal than education. Education is the key to a society’s economic development, growth, innovation, dynamism and prosperity. In May, the World Education Forum was held in the Republic of Korea – a magnificent example of the power of education transform a country ravaged by war and poverty and turn it into an economic powerhouse.

But education must be for all of us. If you educate a girl, you change her country. If you change her country, you can change the world. Terrorism – such as Boko Haram, and the men who shot Malala – engages in such atrocities precisely because they know what the power of educating a girl means for truly transforming the world. With equal urgency, we need to implement more effective programs to ensure that children who are deprived of their education by war, famine, natural disasters and epidemics can be given access to education should they be displaced or made refugees.

We can no longer let a child of 5 become an adolescent at 15 – with their education on hold since childhood in a void of a life disrupted by cruel events beyond their control. Gordon Brown, former prime minister of the UK and now the UN Special Envoy for Education, has been leading this effort with urgency and passion – and we at GPE are working closely with him to step up and address this chronic problem.

Education is about learning, and learning is about choices. And we have a choice, as a world community, this year, in 2015:

Will we simply say the good words, and pledge fidelity to their fulfilment when the world’s leaders gather in New York in September?

Or will we, as leaders in global education meeting in Oslo next month, begin to unlock the financing solutions to what is needed?

And will we make the real and meaningful commitments – just as the UK government has through DFID – to guarantee the resources required to make transforming improvements in the future of our children – the poorest, the most marginalised, those fleeing catastrophe, those who instinctively want to grasp a better future.

Throughout this year, I have felt a strong and growing sense of convergence and consensus among those most committed to these goals – that this is the time, this is our fight, this is our commitment. There is a rising tide of optimism on this fundamental quest for quality education for all in order to forge a better world.

And we will succeed.

(Julia Rigard is the former Prime Minister of Australia.)