Aakash Mehrotra :

You may have heard of Patan because of its Patola sarees, but Aakash Mehrotra says you should also visit it for Rani Ki Vav, the 11th century water conservation marvel

As a kid, I was fascinated by the ingenious architecture of the Shahi Baoli in Imambara, Lucknow. It was the beginning of my love for stepwells. When Rani ki Vav, an 11th century stepwell, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site I couldn’t help but visit. It was a two-hour drive from Ahmedabad to Patan, the ancient capital of the Solanki rulers.

A few steps ahead of the Vav’s unimposing entrance, is the stepped corridor leading to the well’s bottom. What I saw, was nothing short of a subterranean palace. The attention that designers had paid to its aesthetics spoke of the Solanki rulers’ eye for art and architecture. A rectangular passage cuts into earth, plunging downward, leading to the well, bolstered with stoned walls, chiselled with a dizzying range of sculptures, friezes, niches and carvings. A glimpse of the architecture and sculpturing of this mammoth structure could very well be the ‘OMG’ moment of your life. No stone is left un-carved, even the smallest of spaces are geometrically designed.

A magnificent platform rests on beautifully carved pillars. The corridor walls have tiered sets of sculptures arrayed in sunken niches and projecting panels. As I descend the stairs, spectacular beams and columns catch my attention. At the third and largest section of the corridor you feel like surrendering yourself to the munificence of the monument’s art. The colonnades supporting elaborately carved lintels, the sharp contours of the column and beams, embellishments with geometrical motifs and bands of floral designs with repeated geometric patterns gracefully preserved over

the years, give you an impression that you’re entering a millennium-old, well-preserved museum.

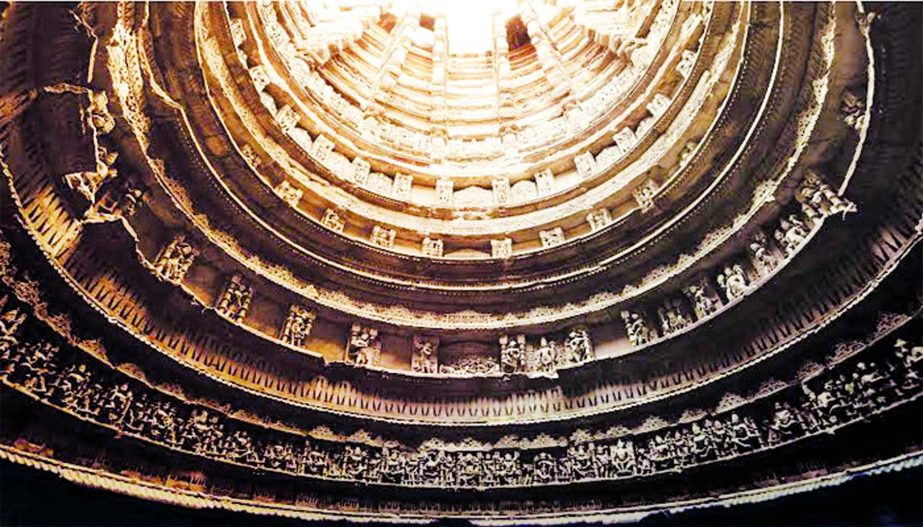

As you go down to the third and last storey, you’ll find seven galleries dedicated to Lord Vishnu. Here hundreds of sculptures depicting his das (ten) avatars are carved so intricately that they seem life-like; they are accompanied by sculttures of other Hindu gods and celestial beings. These enigmatic sculptures harmoniously blend with geometric patterns, sinuous bands of flowers and cusped leaves in a celebration of creativity. The well’s shaft is also carved and divided into seven horizontal sculpture-adorned rows. Its top portion has large brackets, the central part has niches of Seshasayi (Vishnu on the serpent deity) and the rest has divine couples. Looking at the open sky through rings of friezes from down here one discovers the unique relation between light and shadows in the monument.

The well’s lowermost level, covered with silt, was the royal family’s escape route and is said to connect to the Sun Temple, Modhera, 30km away.

The onslaught of time is evident-the upper storey’s roof and torana (pillared gateway) are missing and many sculptures are dismembered, but the grandeur of this three-storeyed subterranean marvel is intact. Archeological Survey of India dug out and restored the structure in 1987. As Marcel Proust said, “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

To capture Rani ki Vav’s elegance and élan one needs many eyes-it was a product of dexterity not just in architecture, but also in thought. After all, the structure was built for water conservation.n

You may have heard of Patan because of its Patola sarees, but Aakash Mehrotra says you should also visit it for Rani Ki Vav, the 11th century water conservation marvel

As a kid, I was fascinated by the ingenious architecture of the Shahi Baoli in Imambara, Lucknow. It was the beginning of my love for stepwells. When Rani ki Vav, an 11th century stepwell, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site I couldn’t help but visit. It was a two-hour drive from Ahmedabad to Patan, the ancient capital of the Solanki rulers.

A few steps ahead of the Vav’s unimposing entrance, is the stepped corridor leading to the well’s bottom. What I saw, was nothing short of a subterranean palace. The attention that designers had paid to its aesthetics spoke of the Solanki rulers’ eye for art and architecture. A rectangular passage cuts into earth, plunging downward, leading to the well, bolstered with stoned walls, chiselled with a dizzying range of sculptures, friezes, niches and carvings. A glimpse of the architecture and sculpturing of this mammoth structure could very well be the ‘OMG’ moment of your life. No stone is left un-carved, even the smallest of spaces are geometrically designed.

A magnificent platform rests on beautifully carved pillars. The corridor walls have tiered sets of sculptures arrayed in sunken niches and projecting panels. As I descend the stairs, spectacular beams and columns catch my attention. At the third and largest section of the corridor you feel like surrendering yourself to the munificence of the monument’s art. The colonnades supporting elaborately carved lintels, the sharp contours of the column and beams, embellishments with geometrical motifs and bands of floral designs with repeated geometric patterns gracefully preserved over

the years, give you an impression that you’re entering a millennium-old, well-preserved museum.

As you go down to the third and last storey, you’ll find seven galleries dedicated to Lord Vishnu. Here hundreds of sculptures depicting his das (ten) avatars are carved so intricately that they seem life-like; they are accompanied by sculttures of other Hindu gods and celestial beings. These enigmatic sculptures harmoniously blend with geometric patterns, sinuous bands of flowers and cusped leaves in a celebration of creativity. The well’s shaft is also carved and divided into seven horizontal sculpture-adorned rows. Its top portion has large brackets, the central part has niches of Seshasayi (Vishnu on the serpent deity) and the rest has divine couples. Looking at the open sky through rings of friezes from down here one discovers the unique relation between light and shadows in the monument.

The well’s lowermost level, covered with silt, was the royal family’s escape route and is said to connect to the Sun Temple, Modhera, 30km away.

The onslaught of time is evident-the upper storey’s roof and torana (pillared gateway) are missing and many sculptures are dismembered, but the grandeur of this three-storeyed subterranean marvel is intact. Archeological Survey of India dug out and restored the structure in 1987. As Marcel Proust said, “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

To capture Rani ki Vav’s elegance and élan one needs many eyes-it was a product of dexterity not just in architecture, but also in thought. After all, the structure was built for water conservation.n