This is a collection of English translation of selected poems by Muhammad Samad (of Bangladesh) who has earned considerable fame here over time for both his poetry and various sorts of activism. As we know well, these two have their markedly separate domains, but are generally found to originate from common source-points, of passions, and to proceed interactively. That means these tend to influence each other. As a result, there’s a risk of one’s performance in both or either of these areas suffering. Readers in Bangladesh keeping watchful eyes on Samad’s poetry now feel relieved that his poetry has rather emerged as a richer volume because of his activism. To take an example of similar appreciation, we find an American critic coming to write the following about Wole Soyinka, whose plays were the subject of my doctoral research, “… his social activism-in particular his fearless opposition to suppression of any kind-renders him a charismatic and inspiring figure.” And, this is true of so many other writers and artists of all times and of all places!

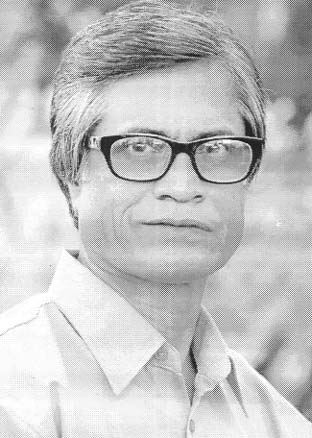

Muhammad Samad was born in 1956 in Jamalpur of Bangladesh. He joined student politics and was an activist of progressive students’ organisation that worked for the creation of People’s Republic of Bangladesh. And, in turn, he can be guessed to have been worked upon by ideologies of Bangladesh’s liberation war, like democracy, nationalism, secularism, socialism, etc. These surely have shaped or oriented his poetry, but in the mysterious ways of creativity. As I myself perceived the situation, Samad’s later activism, at least in the part of Jatio Kabita Parishad (an anti-autocracy movement and organisation of poetry in Bangladesh), etc., rather exposed him to quality poets and their poetry. And, he rather learnt for sure that poetry and activism cannot take each other’s place. Or, they haven’t got much to do with each other. Poetry has to be written in its own age-old ways of deep brooding, intense contemplation and technical perfection, etc., and activism cannot help one out in all these. It may rather create distraction and easy-sailing attitudes. Muhammad Samad pursued his two careers-of a poet and an activist-with equal attention, and thus gained in competence in both. His activism in liberal politics and culture, by honing and strengthening his passions, contributed to his poetry. Reversely, poetry contributed to his activism in some mysterious ways. Finally, ours is no loss in either area; we mark gains in both. Muhammad Samad constitutes one rare instance of success in striding two boats or horses at one time. Sufficient awareness of the difficulties involved, passionate commitment to the two callings, which may have a unique meeting point in a person, etc., have already led to remarkable achievement for Samad and signal much more.

All these I mention; for, they are unforgettable in Muhammad Samad’s case. And, because one may feel shy of mentioning them for the particular time we are passing through. Now is the time in Bangladesh of turning your eyes in poems away from people or popular causes, of attending only to technicalities of perfection, being more wordy and less meaningful, and being ‘post-modern’ in some such ways. These are issues of later-time theory/ies, and Muhammad Samad, who started writing poems in the nineteen-seventies, appears to have cared little for them. His poetry crosses subtleties of theory-debates, and proves an orientation to what might much afterwards and much more be called romantic revolutionism. And, Samad’s and many others’ kinds of poems prove theories, of any imposed kind for our situation, redundant. They prove that creative works can do well by responding firsthand to vistas and varieties in life and by disregarding ideology or theory as things compulsive or circumscribing guidelines. As Samad casually and frequently places so many myths from the Buddhist and Hindu puranas in his poems, to compare, evoke or explain, we get proofs of his close acquaintance with popular life here, history of Bengal and the particularities of civilisation here, much before we get his secularism or pluralism.

Then I, the son of Shuddhvudhan, will go to the forest,

to the bank of the river, Niranjana,

Shady places under the peapul,

Altar of black stone.

Cooking frumenty of your own hand

with milk, water, fruit,

treading on stormy forests

you will awaken me on the night of full moon of Baishakh

Then I shall become Bodhisattva, you, Budhagaya-Village Urubela;

Every one will come to know, the pretty daughter of the Milkman is another Sujata.

Samad however proves enough knowledge of post-modernism, etc., and in a remarkable poem, ‘Crow’, hints at how the ‘theories’ are rather imposed for Bangladesh’s poetry at present:

I find it difficult to make out the behavior of the crows of Ted Huges

They are anyhow post-modern

The crows of Bengal are eternal like my simple mother

All along they talk about our good and bad

Hold meetings for freeing the world from garbage,

………………………………………………

All morning-crows are my younger sisters

They awaken my daughters and seat them at reading-tables

They send my father to the eastern sky with plough

and call my mother to bow in prayer

And, shout out to the world and say…

Sister, get up and keep well – our throats are about to

burst crowing, right now those will bleed!

Proper sensitivity of a poet makes Samad not only modern or liberal; he proves the balance of an opposition to fundamentalist violence in Bangladesh and imperialist menace in Iraq also. In a moving poem about Ali Ismail Abbas, an Iraqi child who has lost both his hands, Samad carries all the wind from the sail of the American war in Iraq; let me quote a portion:.

Maa,

this picture of a boy with his two hands chopped off, his body burnt,

his face distorted by pain; this picture is Ali’s. What’s his fault

in the eyes of Bush and Blair? Why did they cut off his hands?

Maa, how will Ali now ride his bicycle?

How will he hold the stick on his ice-cream?

How will he enjoy the ride on the merry-go-round at the Children’s Park?

How will he embrace others on the day of the Eid?

Or cut the cake on his birthday?

During the Puja or Christmas or the summer fair of Baishakh, Ali will

no more be able to go about holding the hand

of his parents and look for toys…

Muhammad Samad is a genius and popular poet of Bengali language. He has been writing poems since his school days. The first book of his verses Ekjan Rajnaitik Netar Menifesto (Manifesto of a Political Leader) was published in 1983 and won the Trivuj Literary Award in the same year from among the young poets aged 25 years in Bangladesh. His other published books of verses are Selected Poems (bi-lingual),Aamar Duchokh Jale Bhare Jay (My Eyes Get Filled with Tears), Premer Kabita (Love Poems) Kabitasangraha (Selected Collection of Poems), Aaj Sharater Akashe Purnima (The Full Moon in the Autumn Sky) Cholo, Tumi Bristite Bhiji (Let Us Be Drenched in Torrential Rain), Podabe Chandan Kaath (Will Burn Sandal Wood) Ami Noi Indrajit Megher Adale (I am not Indrajit Behind the Clouds). But, again, number or quantity cannot place a full measure of Samad’s poetry. His poetry belongs and takes p-art in composing the poetry part of literature that goes along with popular life of Bangladesh. His poetry forms a part of the literary body that proceeds paralleling mainstream politics of Bangladesh.

In translation, Muhammad Samad’s original line-lengths and stanza-schemes have been kept intact as far as possible. As his are poems rooted in Bangladesh’s age-old culture, folklore, etc., references and allusions are not few, requiring notes which have been placed in a glossary. And, this has been placed at the starting pages, for readers’ convenience. As a fellow poet from Bangladesh, I feel honoured in writing this prose-item which is never an Introduction proper; this is a friend’s contribution that began with translation of some of the poems published here.

(Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka)