AP, Yangon :

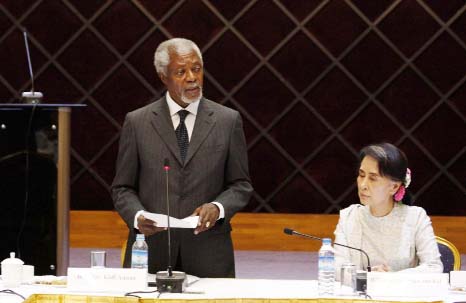

Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi expressed confidence Monday that former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan and a commission he is leading to resolve religious conflict in western Rakhine state will help heal the “wounds of our people,” even as the state’s most powerful political party refused to meet with the panel.

The Southeast Asian country set up the commission last month to help find solutions to “protracted issues” in Rakhine, where human rights groups have documented widespread abuses against minority Rohingya Muslims.

Majority Buddhists in Rakhine and across Myanmar consider Rohingya to be Bangladeshis living in the country illegally, though the ethnic group has been in Myanmar for generations. Hundreds of Rohingya were killed and tens of thousands forced to flee their homes in 2012 unrest, and many continue to be confined to squalid camps.

“You will see for yourself all the problems on the ground now,” Suu Kyi, officially Myanmar state counselor and foreign minister, told commission members at a news conference. “You will be able to assess for yourself of the roots of the problems itself, not in one day, not in one week. But I am confident that you will get there, that you will find the answers because you are truly intent on looking for them.”

The effort is separate from peace talks that began last week with the government and many ethnic groups that have been at war with it for decades.

“There is a wound that hurts all of us,” Suu Kyi said. “And it is because we wish to heal all the wounds of our nation, all the wounds of our people that we look toward Kofi Annan and all the members of the commission to help us to find a way forward.”

The commission is to address human rights, ensuring humanitarian assistance, rights and reconciliation, establishing basic infrastructure and promoting long-term development plans.

Annan said he is “confident that we can assist the people of Rakhine to chart the common path to the peaceful and prosperous future.”

Annan and the commission on Tuesday begin a six-day Rakhine trip during which they will see the camps and meet members of political and religious groups.

But Rakhine’s largest party, the Arakan National Party, which represents the interests of the Buddhist Rakhine majority, said it will not work with the commission.

“We don’t want this commission because we don’t want a foreigner’s human rights perspectives without actually understanding and evaluating the history of Rakhine people, and how can they know the root causes of the conflicts,” ANP secretary Tun Aung Kyaw told The Associated Press by telephone. “Whenever the United Nations’ representatives … came here, they never stood for Rakhine and didn’t do the true reports from Rakhine side.”

He said that if Annan “wants to meet us personally, not as a commission, then we can meet him to show respect.”

Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi expressed confidence Monday that former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan and a commission he is leading to resolve religious conflict in western Rakhine state will help heal the “wounds of our people,” even as the state’s most powerful political party refused to meet with the panel.

The Southeast Asian country set up the commission last month to help find solutions to “protracted issues” in Rakhine, where human rights groups have documented widespread abuses against minority Rohingya Muslims.

Majority Buddhists in Rakhine and across Myanmar consider Rohingya to be Bangladeshis living in the country illegally, though the ethnic group has been in Myanmar for generations. Hundreds of Rohingya were killed and tens of thousands forced to flee their homes in 2012 unrest, and many continue to be confined to squalid camps.

“You will see for yourself all the problems on the ground now,” Suu Kyi, officially Myanmar state counselor and foreign minister, told commission members at a news conference. “You will be able to assess for yourself of the roots of the problems itself, not in one day, not in one week. But I am confident that you will get there, that you will find the answers because you are truly intent on looking for them.”

The effort is separate from peace talks that began last week with the government and many ethnic groups that have been at war with it for decades.

“There is a wound that hurts all of us,” Suu Kyi said. “And it is because we wish to heal all the wounds of our nation, all the wounds of our people that we look toward Kofi Annan and all the members of the commission to help us to find a way forward.”

The commission is to address human rights, ensuring humanitarian assistance, rights and reconciliation, establishing basic infrastructure and promoting long-term development plans.

Annan said he is “confident that we can assist the people of Rakhine to chart the common path to the peaceful and prosperous future.”

Annan and the commission on Tuesday begin a six-day Rakhine trip during which they will see the camps and meet members of political and religious groups.

But Rakhine’s largest party, the Arakan National Party, which represents the interests of the Buddhist Rakhine majority, said it will not work with the commission.

“We don’t want this commission because we don’t want a foreigner’s human rights perspectives without actually understanding and evaluating the history of Rakhine people, and how can they know the root causes of the conflicts,” ANP secretary Tun Aung Kyaw told The Associated Press by telephone. “Whenever the United Nations’ representatives … came here, they never stood for Rakhine and didn’t do the true reports from Rakhine side.”

He said that if Annan “wants to meet us personally, not as a commission, then we can meet him to show respect.”