Literature Desk :

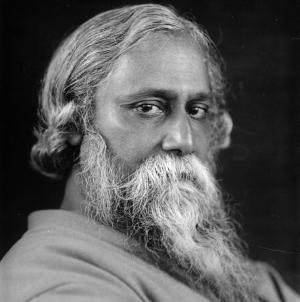

A remarkable aspect of Rabindranath Tagore’s life is the way his persona had changed radically from the restricted identity of an oriental romantic-mystic to the wide-ranging identity of a concerned citizen of the world. A poet, who had earlier attempted to blend spiritual and romantic notions in his quest of grasping the mystery surrounding individual human soul and the divine, increasingly began to give voice to the minds of the colonised and oppressed people and expressed his passionate desire to be identified as one of them. This absolutely stunning transformation is manifested in the non-conformist and modernist approach of his later works. Quite obviously, this aspect of his life was somewhat overlooked by his ostensible admirers who have imposed upon him the title ‘Gurudev’ and converted him into a sacred idol. W B Yeats, who was primarily responsible for forming the synthetic image of Tagore as a mystic poet in the West found problems with his later works. Amartya Sen in his brilliant essay Tagore and his India, has rightly pointed out that the “neglect and even shrill criticism” that Tagore’s later writings received from these early admirers arose from the “inability of Tagore’s many-sided writings to fit into the narrow box” in which they wanted to place and keep him. “To those who do not read Bengali, Tagore is exclusively a literary person or a mystic of sorts,” regrets historian Tapan Roychoudhury. He further clarifies, “The fact that some two-thirds of his writings are serious essays, mostly on political and socio-economic problems of India and the crisis of civilisation has been more or less ignored in Tagore scholarship.”

The crucial social and political transformations that were taking place all over the world including his own country was clearly the principal reason that had caused Tagore to take on such an inclusive approach. During his later years, his concerned voice was heard loud and clear on every moments of crisis that has taken place on every corner of the globe. Viewing through the “crumbling ruins of a proud civilization strewn like a vast heap of futility,” he became disillusioned by history but firmly remained a quintessential optimist to declare: “I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in Man”. Instead of getting dispirited, he became more and more responsive to the great rush of toiling people who works from age to age on the “ruins of hundreds and hundreds of empires.” He had lamented about the ‘missing notes’ of his flute, about his lack of strength to break fences and enter the lives of the peasants, weavers and fisherman. He had also recognised that art becomes fake merchandise if it can’t link life to life. With a candid admission about his own failure in this regard, he had eagerly awaited for the close to the earth poet to give voice to the voiceless hearts. He had intensely aspired for the day when “unvanquished Man will retrace his path of conquest, despite all barriers, to win back his lost human heritage.”

Tagore was profoundly influenced by the liberal humanistic thoughts of nineteenth-century Bengali intellectuals like Ram Mohan Roy, Iswarchandra Vidyasagar, Keshab Chandra Sen and Swami Vivekananda and inherited a rich legacy from them. The seeds of humanitarian concerns were sowed in the mind of a young Tagore when his father Debendranath sent him to live and manage the Tagore family’s rural estates in East Bengal and Orissa. He was then twenty-nine. His stint as a Zamindar (landlord) became a life-transforming experience for him since it was in these rural terrains where for the first time in his life he got the opportunity to observe the socio-economic conditions of his country.

While living in the estate buildings of Shilaidaha and Shahzadpur and in the houseboat Padma for a substantial period, he came into direct touch with the existing economic and social wretchedness of the peasants who lived under “the worse indifference of a rigid social orthodoxy and of an alien political rule”. From “a great tenderness for these peasant folk,” he felt a deep urge to extend his aesthetic, philosophic and socio-political ideas beyond its thin intellectual space and started thinking seriously about social reform and reconstruction as the principle means for liberating the people of his country. But he was still skeptical about the shortcomings of his “middle class background” which he thought might stand in his way of doing something for the rural people because, “…whenever the middle class Babus intend to do something for the rural people, they show their contempt for them.”

“There he had made two important discoveries,” wrote Tagore’s English colleague Leonard Elmhirst, “first, that the villagers seemed to have lost all ability to help themselves; secondly, that both research and technical assistance would be needed if they were ever to learn how to rescue themselves from their creeping decay.” While travelling all around the vast estate to collect annual rents from the ryots (peasants), Tagore visited villages, conversed with the poor villagers, listened to their problems and also witnessed the worse indifference that affected their lives. Depicting his experiences as the “hideous nightmare of our present time,” an inundated Tagore later wrote, “Our so-called responsible classes live in comfort because the common man has not yet understood his situation. That is why the landlord beats him. The money-lender holds him in his clutches; the foreman abuses him; the policeman fleeces him; the priest exploits him; and the magistrate picks his pocket.” Although at this stage, his attitude towards the impoverished masses was of a romantic onlooker as he was still not well-acquainted with the basic complexities of land relations and the socio-economic rationale behind the privation and helplessness of the subaltern class. But he was definitely trying to understand the prevailing social contradictions through his daily encounters with the rural people.

In the introduction of W. W. Pearson’s book Shantiniketan, Tagore had described how he “woke up to the call of the spirit of my country” and felt the urge to dedicate his life in “furthering the purpose that lies in the heart of her history”. Ideas that had originated in his mind while spending a great part of his youth in the riverside solitude of Shilaidaha become deep rooted in his consciousness. These ideas later developed as a highly original and distinctive vision. From a genuine attempt to understand the problems, he gradually came to realise the necessity of rural reconstruction as the real solution to India’s problems. Instead of idealising rural life, he started to sense that poverty can be dealt through the spread of basic education, by inducing self-reliance among the peasants, through the application of scientific methods to agriculture, setting up cottage industries and cooperative banks.

He came to realise that the greatest enemies of India are not the outsiders but the forces that reside within its borders. In ‘The Future of India’ he writes, “So long as we, out of personal and collective ignorance, cannot treat our countrymen properly like men, so long as our landlords regard their tenants as a mere part of their property, so long as the strong in our country will consider it the eternal law to trample on the weak, the higher castes despise the lower as worse than beasts, even so long we cannot claim gentlemanly treatment from the English as a matter of right, even so long we shall fail to truly waken the English character, even so long will India continue to be defrauded of her due and humiliated.” To bring his ideas of rural reconstruction into reality, he later went on to establish Sriniketan under the agricultural scientist Leonard Elmhirst.

In 1939, in an address on his last visit to Sriniketan, Tagore spoke about his early Shilaidaha days, “I was filled with eagerness to understand the villagers’ daily routine and the varied pageant of their lives…..Gradually the sorrow and poverty of the villages became clear to me, and I began to grow restless to do something about it. It seemed to me a very shameful thing that I should spend my days as a landlord, concerned only in money making and engrossed with my own profit and loss. From that time onward, I continually endeavoured to find out how the villagers’ mind could be aroused, so that they could themselves accept the responsibility for their own lives.”

A remarkable aspect of Rabindranath Tagore’s life is the way his persona had changed radically from the restricted identity of an oriental romantic-mystic to the wide-ranging identity of a concerned citizen of the world. A poet, who had earlier attempted to blend spiritual and romantic notions in his quest of grasping the mystery surrounding individual human soul and the divine, increasingly began to give voice to the minds of the colonised and oppressed people and expressed his passionate desire to be identified as one of them. This absolutely stunning transformation is manifested in the non-conformist and modernist approach of his later works. Quite obviously, this aspect of his life was somewhat overlooked by his ostensible admirers who have imposed upon him the title ‘Gurudev’ and converted him into a sacred idol. W B Yeats, who was primarily responsible for forming the synthetic image of Tagore as a mystic poet in the West found problems with his later works. Amartya Sen in his brilliant essay Tagore and his India, has rightly pointed out that the “neglect and even shrill criticism” that Tagore’s later writings received from these early admirers arose from the “inability of Tagore’s many-sided writings to fit into the narrow box” in which they wanted to place and keep him. “To those who do not read Bengali, Tagore is exclusively a literary person or a mystic of sorts,” regrets historian Tapan Roychoudhury. He further clarifies, “The fact that some two-thirds of his writings are serious essays, mostly on political and socio-economic problems of India and the crisis of civilisation has been more or less ignored in Tagore scholarship.”

The crucial social and political transformations that were taking place all over the world including his own country was clearly the principal reason that had caused Tagore to take on such an inclusive approach. During his later years, his concerned voice was heard loud and clear on every moments of crisis that has taken place on every corner of the globe. Viewing through the “crumbling ruins of a proud civilization strewn like a vast heap of futility,” he became disillusioned by history but firmly remained a quintessential optimist to declare: “I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in Man”. Instead of getting dispirited, he became more and more responsive to the great rush of toiling people who works from age to age on the “ruins of hundreds and hundreds of empires.” He had lamented about the ‘missing notes’ of his flute, about his lack of strength to break fences and enter the lives of the peasants, weavers and fisherman. He had also recognised that art becomes fake merchandise if it can’t link life to life. With a candid admission about his own failure in this regard, he had eagerly awaited for the close to the earth poet to give voice to the voiceless hearts. He had intensely aspired for the day when “unvanquished Man will retrace his path of conquest, despite all barriers, to win back his lost human heritage.”

Tagore was profoundly influenced by the liberal humanistic thoughts of nineteenth-century Bengali intellectuals like Ram Mohan Roy, Iswarchandra Vidyasagar, Keshab Chandra Sen and Swami Vivekananda and inherited a rich legacy from them. The seeds of humanitarian concerns were sowed in the mind of a young Tagore when his father Debendranath sent him to live and manage the Tagore family’s rural estates in East Bengal and Orissa. He was then twenty-nine. His stint as a Zamindar (landlord) became a life-transforming experience for him since it was in these rural terrains where for the first time in his life he got the opportunity to observe the socio-economic conditions of his country.

While living in the estate buildings of Shilaidaha and Shahzadpur and in the houseboat Padma for a substantial period, he came into direct touch with the existing economic and social wretchedness of the peasants who lived under “the worse indifference of a rigid social orthodoxy and of an alien political rule”. From “a great tenderness for these peasant folk,” he felt a deep urge to extend his aesthetic, philosophic and socio-political ideas beyond its thin intellectual space and started thinking seriously about social reform and reconstruction as the principle means for liberating the people of his country. But he was still skeptical about the shortcomings of his “middle class background” which he thought might stand in his way of doing something for the rural people because, “…whenever the middle class Babus intend to do something for the rural people, they show their contempt for them.”

“There he had made two important discoveries,” wrote Tagore’s English colleague Leonard Elmhirst, “first, that the villagers seemed to have lost all ability to help themselves; secondly, that both research and technical assistance would be needed if they were ever to learn how to rescue themselves from their creeping decay.” While travelling all around the vast estate to collect annual rents from the ryots (peasants), Tagore visited villages, conversed with the poor villagers, listened to their problems and also witnessed the worse indifference that affected their lives. Depicting his experiences as the “hideous nightmare of our present time,” an inundated Tagore later wrote, “Our so-called responsible classes live in comfort because the common man has not yet understood his situation. That is why the landlord beats him. The money-lender holds him in his clutches; the foreman abuses him; the policeman fleeces him; the priest exploits him; and the magistrate picks his pocket.” Although at this stage, his attitude towards the impoverished masses was of a romantic onlooker as he was still not well-acquainted with the basic complexities of land relations and the socio-economic rationale behind the privation and helplessness of the subaltern class. But he was definitely trying to understand the prevailing social contradictions through his daily encounters with the rural people.

In the introduction of W. W. Pearson’s book Shantiniketan, Tagore had described how he “woke up to the call of the spirit of my country” and felt the urge to dedicate his life in “furthering the purpose that lies in the heart of her history”. Ideas that had originated in his mind while spending a great part of his youth in the riverside solitude of Shilaidaha become deep rooted in his consciousness. These ideas later developed as a highly original and distinctive vision. From a genuine attempt to understand the problems, he gradually came to realise the necessity of rural reconstruction as the real solution to India’s problems. Instead of idealising rural life, he started to sense that poverty can be dealt through the spread of basic education, by inducing self-reliance among the peasants, through the application of scientific methods to agriculture, setting up cottage industries and cooperative banks.

He came to realise that the greatest enemies of India are not the outsiders but the forces that reside within its borders. In ‘The Future of India’ he writes, “So long as we, out of personal and collective ignorance, cannot treat our countrymen properly like men, so long as our landlords regard their tenants as a mere part of their property, so long as the strong in our country will consider it the eternal law to trample on the weak, the higher castes despise the lower as worse than beasts, even so long we cannot claim gentlemanly treatment from the English as a matter of right, even so long we shall fail to truly waken the English character, even so long will India continue to be defrauded of her due and humiliated.” To bring his ideas of rural reconstruction into reality, he later went on to establish Sriniketan under the agricultural scientist Leonard Elmhirst.

In 1939, in an address on his last visit to Sriniketan, Tagore spoke about his early Shilaidaha days, “I was filled with eagerness to understand the villagers’ daily routine and the varied pageant of their lives…..Gradually the sorrow and poverty of the villages became clear to me, and I began to grow restless to do something about it. It seemed to me a very shameful thing that I should spend my days as a landlord, concerned only in money making and engrossed with my own profit and loss. From that time onward, I continually endeavoured to find out how the villagers’ mind could be aroused, so that they could themselves accept the responsibility for their own lives.”