Weekend Plus Desk :

Sayyiyan nikal gaye, main na ladi thi/ Na jaane kaunsi khidki khuli thi (My beloved left and I didn’t put up a fight, I didn’t know which window was open)

This lament by Janki Bai Ilahabadi was penned by poet Kabir as a bhajan, which was a reference to death and one’s soul leaving the body. Janki Bai turned it into a thumri in the early 20th century and sang it in mehfils and soirees at the royal durbars that courted her and had those present throwing silver coins at her feet. Later, the piece found a place in popular consciousness. It was featured in Lata Mangeshkar’s voice in Raj Kapoor’s Satyam Shivam Sundaram, was sung often by thumri legend Shobha Gurtu and is still featured in concerts by Kaushiki Chakraborty, among others.

In this HMV recording, the recording company’s first one and now available on YouTube, Janki Bai sings the lyrics in her robust, slightly high-pitched voice, as if the words are a reference to her beloved, the one who left her at night and took away her soul with her. She also changes the word nikas into nikal, probably because the latter is easier to play around phonetically. A little less than three-minute-long, the piece reaches its sublime note and ends with the sentence: Mera naam Janki Bai Illahabad. “I took an instant liking to her,” says Neelum Saran Gour, a literature professor at University of Allahabad, who’s now written Requiem in Raga Janki (Penguin, Rs 599).

It was Gour’s visit to Kolkata’s ITC Sangeet Research Academy 30 years ago, which threw up the name Janki Bai Illahabadi. Gour didn’t know much of this Hindustani vocalist who lived a century ago in her city, and died in 1936.

The name came up again in 2008 while researching the heritage of Allahabad for a book. She came across a brief biography of Janki Bai and was struck by the person behind the icon. “I also wondered why not much had been written about her and why she wasn’t well-known even in Allahabad,” says Gour, who then came across some of her records with passionate record collectors and realised that most of her music was lost. “She, in her time, was as big a star as Amitabh Bachchan from Allahabad,” says Gour, who isn’t trained in music but grew up listening to a lot of it from her musician father and has always written stories based in and on Allahabad. Her other books include Grey Pigeon and Other Stories, Sikandar Chowk Park, Song Without and Other Stories.

Born in Varanasi in 1880, Janki Bai and her mother, Manki, were abandoned by her father, Shivbalakram, a wrestler, after he took on a mistress. Manki and Janki came to Allahabad, where the two were sold to the owner of a kotha. Manki began to run the place after the owner died and decided to train her daughter in Hindustani classical music and got Hassu Khan of Lucknow to train her.

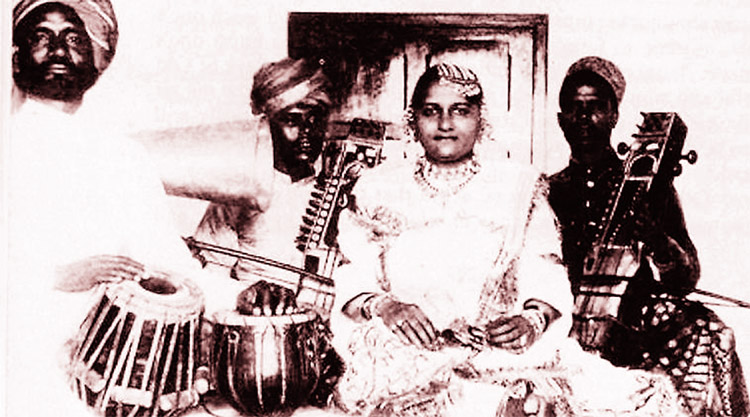

Janki grew up to be a popular courtesan and became close friends with Gauhar Jaan of Calcutta and the two sang together in 1911 at Attarsuiya thana, when King George V visited Allahabad. As the story goes, he was mesmerised with their performance and gave 100 guineas to the two. She recorded 22 shellac discs in her career. But the name didn’t trickle down into popular consciousness.

A search for Janki Bai also led Gour to a crumbling monument in Kaladanda Kabristaan in Allahabad’s Adarsh Nagar that is called Chhappan Chhuri ki Mazaar. Janki Bai was called Chhappan Chhuri – she of the 56 knife gashes.

Janki Bai acquired the name when, according to the legend, she was attacked by Raghunandan, a police constable when he was denied sexual favours from a 12-year-old. He came one day and scarred her face with 56 gashes. The book takes us through the life and times of a woman who has been scarred and is rebuked by men, but has to turn to them later for patronage.

“There wasn’t a choice here but she also wanted to be loved,” says Gour.

Janki Bai would often sing from behind a curtain, revealing her face, only when her patron was in love with her voice.

“In her life, like that of other artistes, I found a permanent situation- life in real time, life in art; the troubled vexed life and that fabulous artistic life. Art stepped in where life failed her,” says Gour.

The stories are mostly from her own writings or passed down to music lovers from an older generation. To fill in the gaps, Gour has used fiction. Real stories are there but, more often than not, the fiction tends to exceed the reality in the stories.

Gour says, “You assume that there is an authentic narrative, which is reduced to suit the demands of fiction. I feel that one fictionalises when there are gaps in the historical narrative. That’s where you intuit and infer. You don’t lose but add to the known fact. You step into the areas of silence and doubts and write,” says Gour, who has used two storytellers describing the story, writing a lot of conversations in extremely flowery archaic English, which can sometimes seem jarring. But Gour feels “it was the only way to project the right combination of Urdu and Hindi.”

The book, which tells two simultaneous stories, one from an aging baiji and other the documented history of a colonial India, has significant blind spots. Gour does not delve into German recording technology that changed the face of Indian music industry or the times in which Janki Bai lived and how the concert culture was coming up and the baithak style and aristocracy were on a decline. “There are always dimensions that could have been. I am only accountable for what I have done. I was dealing with one character and her inward relation with her art,” says Gour. n

Sayyiyan nikal gaye, main na ladi thi/ Na jaane kaunsi khidki khuli thi (My beloved left and I didn’t put up a fight, I didn’t know which window was open)

This lament by Janki Bai Ilahabadi was penned by poet Kabir as a bhajan, which was a reference to death and one’s soul leaving the body. Janki Bai turned it into a thumri in the early 20th century and sang it in mehfils and soirees at the royal durbars that courted her and had those present throwing silver coins at her feet. Later, the piece found a place in popular consciousness. It was featured in Lata Mangeshkar’s voice in Raj Kapoor’s Satyam Shivam Sundaram, was sung often by thumri legend Shobha Gurtu and is still featured in concerts by Kaushiki Chakraborty, among others.

In this HMV recording, the recording company’s first one and now available on YouTube, Janki Bai sings the lyrics in her robust, slightly high-pitched voice, as if the words are a reference to her beloved, the one who left her at night and took away her soul with her. She also changes the word nikas into nikal, probably because the latter is easier to play around phonetically. A little less than three-minute-long, the piece reaches its sublime note and ends with the sentence: Mera naam Janki Bai Illahabad. “I took an instant liking to her,” says Neelum Saran Gour, a literature professor at University of Allahabad, who’s now written Requiem in Raga Janki (Penguin, Rs 599).

It was Gour’s visit to Kolkata’s ITC Sangeet Research Academy 30 years ago, which threw up the name Janki Bai Illahabadi. Gour didn’t know much of this Hindustani vocalist who lived a century ago in her city, and died in 1936.

The name came up again in 2008 while researching the heritage of Allahabad for a book. She came across a brief biography of Janki Bai and was struck by the person behind the icon. “I also wondered why not much had been written about her and why she wasn’t well-known even in Allahabad,” says Gour, who then came across some of her records with passionate record collectors and realised that most of her music was lost. “She, in her time, was as big a star as Amitabh Bachchan from Allahabad,” says Gour, who isn’t trained in music but grew up listening to a lot of it from her musician father and has always written stories based in and on Allahabad. Her other books include Grey Pigeon and Other Stories, Sikandar Chowk Park, Song Without and Other Stories.

Born in Varanasi in 1880, Janki Bai and her mother, Manki, were abandoned by her father, Shivbalakram, a wrestler, after he took on a mistress. Manki and Janki came to Allahabad, where the two were sold to the owner of a kotha. Manki began to run the place after the owner died and decided to train her daughter in Hindustani classical music and got Hassu Khan of Lucknow to train her.

Janki grew up to be a popular courtesan and became close friends with Gauhar Jaan of Calcutta and the two sang together in 1911 at Attarsuiya thana, when King George V visited Allahabad. As the story goes, he was mesmerised with their performance and gave 100 guineas to the two. She recorded 22 shellac discs in her career. But the name didn’t trickle down into popular consciousness.

A search for Janki Bai also led Gour to a crumbling monument in Kaladanda Kabristaan in Allahabad’s Adarsh Nagar that is called Chhappan Chhuri ki Mazaar. Janki Bai was called Chhappan Chhuri – she of the 56 knife gashes.

Janki Bai acquired the name when, according to the legend, she was attacked by Raghunandan, a police constable when he was denied sexual favours from a 12-year-old. He came one day and scarred her face with 56 gashes. The book takes us through the life and times of a woman who has been scarred and is rebuked by men, but has to turn to them later for patronage.

“There wasn’t a choice here but she also wanted to be loved,” says Gour.

Janki Bai would often sing from behind a curtain, revealing her face, only when her patron was in love with her voice.

“In her life, like that of other artistes, I found a permanent situation- life in real time, life in art; the troubled vexed life and that fabulous artistic life. Art stepped in where life failed her,” says Gour.

The stories are mostly from her own writings or passed down to music lovers from an older generation. To fill in the gaps, Gour has used fiction. Real stories are there but, more often than not, the fiction tends to exceed the reality in the stories.

Gour says, “You assume that there is an authentic narrative, which is reduced to suit the demands of fiction. I feel that one fictionalises when there are gaps in the historical narrative. That’s where you intuit and infer. You don’t lose but add to the known fact. You step into the areas of silence and doubts and write,” says Gour, who has used two storytellers describing the story, writing a lot of conversations in extremely flowery archaic English, which can sometimes seem jarring. But Gour feels “it was the only way to project the right combination of Urdu and Hindi.”

The book, which tells two simultaneous stories, one from an aging baiji and other the documented history of a colonial India, has significant blind spots. Gour does not delve into German recording technology that changed the face of Indian music industry or the times in which Janki Bai lived and how the concert culture was coming up and the baithak style and aristocracy were on a decline. “There are always dimensions that could have been. I am only accountable for what I have done. I was dealing with one character and her inward relation with her art,” says Gour. n