Literature Desk :

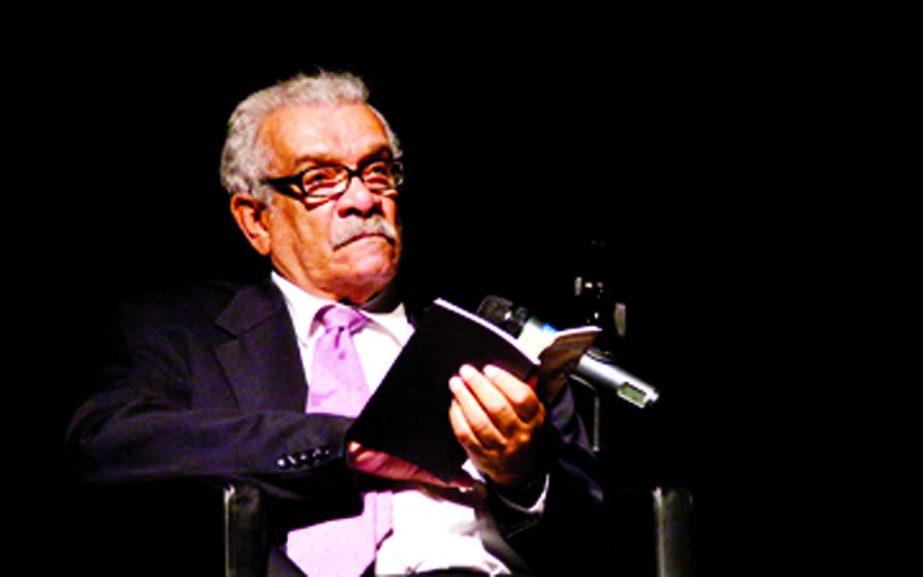

Derek Walcott, a Nobel laureate in literature who became one of the English-speaking world’s most renowned poets by portraying the lush, complex world of the Caribbean with a precise language that echoed the classics of literature, breathed his last on March 17 at his home on the island of St Lucia. He was 87.

Walcott, who was born on the island of St. Lucia and published his first poem at 14, won the Nobel Prize in 1992, becoming the first writer from the Caribbean to receive the honour.

In his poetry and plays, he appropriated Greek classics, local folklore, and the British literary canon in his explorations of the ambiguities of race, history, and cultural identity.

Although he taught for a quarter century at Boston University and later in England, Walcott created a distinctively Caribbean sensibility in his writing, rich with a sense of the weather, warmth, and the rhythms of island life. In one of his early poems, ‘Islands,’ he declared that his poetic ambition was “to write / Verse crisp as sand, clear as sunlight, / Cold as the curved wave, ordinary / As a tumbler of island water.”

His breakthrough came in 1962 with the collection ‘In a Green Night,’ which celebrated the landscape and history of the Caribbean and explored his conflicted identity as a multiracial descendant of a colonial culture. In his 1962 poem ‘A Far Cry From Africa,’ he wrote,

“I who am poisoned with the blood of both,

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the English tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?”

The vibrant quality of Walcott’s poetry was ‘like entering a Renoir,’ British critic P N Furbank wrote in the Listener newspaper in 1962, “full of summery melancholy, fresh and stinging colors, luscious melody, and intense awareness of place.”

In 1973, he published a book-length autobiographical poem, ‘Another Life,’ that touched on his childhood, his spiritual growth, and his struggles to forge an independent identity as an artist.

Walcott went on to publish more than 20 volumes of poetry and virtually as many plays, many of which were produced in the United States and throughout the Caribbean, often with the author as director.

His Nobel Prize citation noted, “In him, West Indian culture has found its great poet.”

As a pure composer of verse, Walcott had few equals in his time. He wrote in a smooth, carefully polished style, usually adhering to the traditional forms of English poetry, such as iambic pentameter, heroic couplets, and rhyme.

Caught between the ‘virginal unpainted world’ of St. Lucia and the historic majesty of the English language, he wrote in his poem ‘The Schooner Flight’ in the 1970s, “I had no nation now but the imagination.”

Walcott started teaching English and playwriting at BU in 1981. He was accused of sexually harassing female students. He was a leading candidate for the position of Professor of poetry at Britain’s University of Oxford in 2009, when the old charges of harassment resurfaced. Walcott condemned what he called a ‘low, degrading attempt at character assassination’ and withdrew his name from consideration. The professorship went to poet Ruth Padel, who soon resigned after admitting that she had forwarded the allegations to journalists.

Walcott published a new volume every year or two, drawing praise from such eminent literary critics as Helen Vendler of Harvard and Harold Bloom of Yale.

He enjoyed the friendship of some of the era’s greatest names in poetry, including Robert Lowell, Joseph Brodsky, and Seamus Heaney. He received many literary honors and in 1981 was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, also known as a genius gran

In 1990, two years before Walcott received the Nobel Prize, he published what many critics considered his masterpiece, the 325-page poem ‘Omeros.’ The ambitious work reimagined the ancient Greek epics of Homer in modern-day St Lucia.

“What drove me was duty: duty to the Caribbean light,” Walcott told the New York Times in 1990. ”The whole book is an act of gratitude. It is a fantastic privilege to be in a place in which limbs, features, smells, the lineaments and presence of the people are so powerful.”

The poem has the scope of a novel, ranging from the Caribbean back in time to ancient Greece, the British Empire, and the 19th-century United States. Walcott evokes Joseph Conrad, Herman Melville, James Joyce, and, of course, Homer – both the ancient Greek poet and Winslow Homer, the American painter of ‘The Gulf Stream.’

The characters in ‘Omeros’ are fishermen who battle the weather and the sea and who struggle with their all-too-human desires and shortcomings. Helen of Troy is recast a haughty St Lucian woman who works as a waitress and sells trinkets at the beach.

“What I wanted to do in the book was to write about very simple people who I think are heroic,” Walcott told NPR in 2007.

Derek Alton Walcott was born in Castries, the capital of St Lucia. The island became an independent country in 1979 after being a British colony for 165 years.

Walcott had a twin brother, Roderick, who became a playwright, and an older sister, Pamela. Their father, a civil servant and skilled watercolor painter, died when he was only 1. His mother taught in school.

While studying at English-language schools, Walcott became devoted to English poetry and received a scholarship to the University of the West Indies in Jamaica.

After teaching in St Lucia, Grenada, and Jamaica, he received a Rockefeller Foundation grant, which he used to study theater in New York.

For years, Walcott wrote as much drama as poetry, and his plays were produced in Caribbean theaters, then in London and Toronto and, by the late 1960s, in off-Broadway theaters in New York.

His plays drew on folk elements and typically were written in a more casual, colloquial style than his poetry.

His play ‘Dream on Monkey Mountain,’ produced off-Broadway, won an Obie Award in 1971. In 1998, he collaborated with singer-songwriter Paul Simon on the musical ‘The Capeman,’ which had a short-lived run on Broadway.

In 1981, with some of his proceeds from the Mac Arthur grant, Walcott founded Boston Playwrights’ Theatre as a showcase for new plays. He wrote several pieces for the stage near BU’s campus and affiliated with the university, including one, ‘Walker,’ that takes a look at Boston’s abolitionist roots through the eyes of the title character, a self-taught free black man.

“The thing I wanted to do was to have the playwright in close contact with the actor, which is something in a professional theatre that you just don’t get,” he told the theater in an interview in 2007.

“I thought the thing that would be best for any playwright . . . was to have a programme in which the actors and the playwrights could relate immediately, and the actors could help in terms of the shaping of the scripts.”

“For those of us who knew and loved him, Derek’s passing is a milestone in our lives – certainly it is in mine,” Kate Snodgrass, BU playwright Professor and Artistic Director at the theater, wrote on the theater’s website. “And for the world, we have lost a needed presence, a gifted poet and playwright, a true literary giant.”

Derek Walcott, a Nobel laureate in literature who became one of the English-speaking world’s most renowned poets by portraying the lush, complex world of the Caribbean with a precise language that echoed the classics of literature, breathed his last on March 17 at his home on the island of St Lucia. He was 87.

Walcott, who was born on the island of St. Lucia and published his first poem at 14, won the Nobel Prize in 1992, becoming the first writer from the Caribbean to receive the honour.

In his poetry and plays, he appropriated Greek classics, local folklore, and the British literary canon in his explorations of the ambiguities of race, history, and cultural identity.

Although he taught for a quarter century at Boston University and later in England, Walcott created a distinctively Caribbean sensibility in his writing, rich with a sense of the weather, warmth, and the rhythms of island life. In one of his early poems, ‘Islands,’ he declared that his poetic ambition was “to write / Verse crisp as sand, clear as sunlight, / Cold as the curved wave, ordinary / As a tumbler of island water.”

His breakthrough came in 1962 with the collection ‘In a Green Night,’ which celebrated the landscape and history of the Caribbean and explored his conflicted identity as a multiracial descendant of a colonial culture. In his 1962 poem ‘A Far Cry From Africa,’ he wrote,

“I who am poisoned with the blood of both,

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the English tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?”

The vibrant quality of Walcott’s poetry was ‘like entering a Renoir,’ British critic P N Furbank wrote in the Listener newspaper in 1962, “full of summery melancholy, fresh and stinging colors, luscious melody, and intense awareness of place.”

In 1973, he published a book-length autobiographical poem, ‘Another Life,’ that touched on his childhood, his spiritual growth, and his struggles to forge an independent identity as an artist.

Walcott went on to publish more than 20 volumes of poetry and virtually as many plays, many of which were produced in the United States and throughout the Caribbean, often with the author as director.

His Nobel Prize citation noted, “In him, West Indian culture has found its great poet.”

As a pure composer of verse, Walcott had few equals in his time. He wrote in a smooth, carefully polished style, usually adhering to the traditional forms of English poetry, such as iambic pentameter, heroic couplets, and rhyme.

Caught between the ‘virginal unpainted world’ of St. Lucia and the historic majesty of the English language, he wrote in his poem ‘The Schooner Flight’ in the 1970s, “I had no nation now but the imagination.”

Walcott started teaching English and playwriting at BU in 1981. He was accused of sexually harassing female students. He was a leading candidate for the position of Professor of poetry at Britain’s University of Oxford in 2009, when the old charges of harassment resurfaced. Walcott condemned what he called a ‘low, degrading attempt at character assassination’ and withdrew his name from consideration. The professorship went to poet Ruth Padel, who soon resigned after admitting that she had forwarded the allegations to journalists.

Walcott published a new volume every year or two, drawing praise from such eminent literary critics as Helen Vendler of Harvard and Harold Bloom of Yale.

He enjoyed the friendship of some of the era’s greatest names in poetry, including Robert Lowell, Joseph Brodsky, and Seamus Heaney. He received many literary honors and in 1981 was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, also known as a genius gran

In 1990, two years before Walcott received the Nobel Prize, he published what many critics considered his masterpiece, the 325-page poem ‘Omeros.’ The ambitious work reimagined the ancient Greek epics of Homer in modern-day St Lucia.

“What drove me was duty: duty to the Caribbean light,” Walcott told the New York Times in 1990. ”The whole book is an act of gratitude. It is a fantastic privilege to be in a place in which limbs, features, smells, the lineaments and presence of the people are so powerful.”

The poem has the scope of a novel, ranging from the Caribbean back in time to ancient Greece, the British Empire, and the 19th-century United States. Walcott evokes Joseph Conrad, Herman Melville, James Joyce, and, of course, Homer – both the ancient Greek poet and Winslow Homer, the American painter of ‘The Gulf Stream.’

The characters in ‘Omeros’ are fishermen who battle the weather and the sea and who struggle with their all-too-human desires and shortcomings. Helen of Troy is recast a haughty St Lucian woman who works as a waitress and sells trinkets at the beach.

“What I wanted to do in the book was to write about very simple people who I think are heroic,” Walcott told NPR in 2007.

Derek Alton Walcott was born in Castries, the capital of St Lucia. The island became an independent country in 1979 after being a British colony for 165 years.

Walcott had a twin brother, Roderick, who became a playwright, and an older sister, Pamela. Their father, a civil servant and skilled watercolor painter, died when he was only 1. His mother taught in school.

While studying at English-language schools, Walcott became devoted to English poetry and received a scholarship to the University of the West Indies in Jamaica.

After teaching in St Lucia, Grenada, and Jamaica, he received a Rockefeller Foundation grant, which he used to study theater in New York.

For years, Walcott wrote as much drama as poetry, and his plays were produced in Caribbean theaters, then in London and Toronto and, by the late 1960s, in off-Broadway theaters in New York.

His plays drew on folk elements and typically were written in a more casual, colloquial style than his poetry.

His play ‘Dream on Monkey Mountain,’ produced off-Broadway, won an Obie Award in 1971. In 1998, he collaborated with singer-songwriter Paul Simon on the musical ‘The Capeman,’ which had a short-lived run on Broadway.

In 1981, with some of his proceeds from the Mac Arthur grant, Walcott founded Boston Playwrights’ Theatre as a showcase for new plays. He wrote several pieces for the stage near BU’s campus and affiliated with the university, including one, ‘Walker,’ that takes a look at Boston’s abolitionist roots through the eyes of the title character, a self-taught free black man.

“The thing I wanted to do was to have the playwright in close contact with the actor, which is something in a professional theatre that you just don’t get,” he told the theater in an interview in 2007.

“I thought the thing that would be best for any playwright . . . was to have a programme in which the actors and the playwrights could relate immediately, and the actors could help in terms of the shaping of the scripts.”

“For those of us who knew and loved him, Derek’s passing is a milestone in our lives – certainly it is in mine,” Kate Snodgrass, BU playwright Professor and Artistic Director at the theater, wrote on the theater’s website. “And for the world, we have lost a needed presence, a gifted poet and playwright, a true literary giant.”