(After last week write-up)

It was in the National Library at Dhaka (1979-84) that ‘distortion’ of the idealised form itself becomes the generator of architecture; the ultimate artifact acknowledges more explicitly the conditions of the ‘place,’ the context and the contradictions. The building, by its geometry, solidity and spatial order, makes a convincing dialogue with the neighboring ensemble by Kahn, which has by now formed an important context or fabric in the north of Dhaka. While geometric abstraction and a consummate skill for physiognomic articulation provide continuity in all his work, the urbanity of National Library is a world removed from the Public Library of 1955.

Muzharul Islam singly formed the first generation of contemporary architects and laid the basis of a profession and an intellectual discipline. His work ultimately seemed too reserved however in proposing an iconography which would be evocative of a Bengali sensibility. This is the concern that seems to engage a group of small but conscientious architects today and this is where the significant thrust of thoughtful production will lie in the future.

Unfortunately, the important promoters of building activity — the state and the upper-middle class clientele groups — still adhere to an image of progress set in some vague idea of industrialisation. The largest group of architects, in quick and easy responses, has continued a fallacious interpretation of the rationality and aesthetics of functionalism and technology-evident in the monolithic expressions, uncritical use of materials and technology, and nonchalance towards the figurative aspect of architecture. Architectural strategies in Bangladesh are locked, to a great degree, within the global politico-economic conditions of today, and within these transitional times when the country is again at a loss for a collective vision. Under such conditions, it is probable that design propositions will still be shaped by an Euro-centric language, but what is really disconcerting is the still uncritical and overt allegiance to it by the majority of the practitioners.

There is a far more undesirable tendency that has found its modus operandi in the worst form of hybridization. By remorselessly implanting neo-Classical devices on Bengali cityscapes, or grafting pseudo-Islamic motifs on European planimetric organisation, this attitude forms the most self-interested group of commercial practitioners, and the more likely agent of trumped-up state ideology. In short, absolved more from the rigors and responsibilities than from stylistic constraints, this group is apt to do the least service, and most damage, to evolving architectural principles.

Finally, within, the overbearing presence of the two tendencies just cited, there is a maturing, committed trend that encompasses an investigative architecture. The central thrust of this group is to evoke the myth and poeisis of the land within the tension of archaicness and comtemporaneity, and global and local pressures. With the paralysis of Bengali architectural sensibility in the last 100 years or so, it has become morally imperative and culturally urgent that a significant portion of contemporary architecture in Bangladesh become ‘archaeological’: to excavate from the historical layers of contradictory and imposed ideologies a more ‘place-responsive’ architecture. The archaeological inquiry is not in the sense of uncovering fossils, nor is it in the sense of a trip to exotica, but rather with the objective of restituting cultural archetypes that still have deep existential significance, and that will be a beginning point for fresh trajectories.

Some of the works of Rabiul Husain (of Shaheedullah Associates) and Bashirul Haq, while employing culturally syncretistic devices, mark the tentative beginning of this research. Bashirul Haq has particularly endeared himself for his notable rendition of private houses-quite, unobtrusive masonry volumes in close affiliation with the setting. His special sensitivity for the domestic realm is meticulously articulated in his own house and studio-light, plantation and construction materials as tactile sensation, and the crafting of space, hierarchical, exterior-interior, private-public, diversely volumed-all create a memorable experience of living.

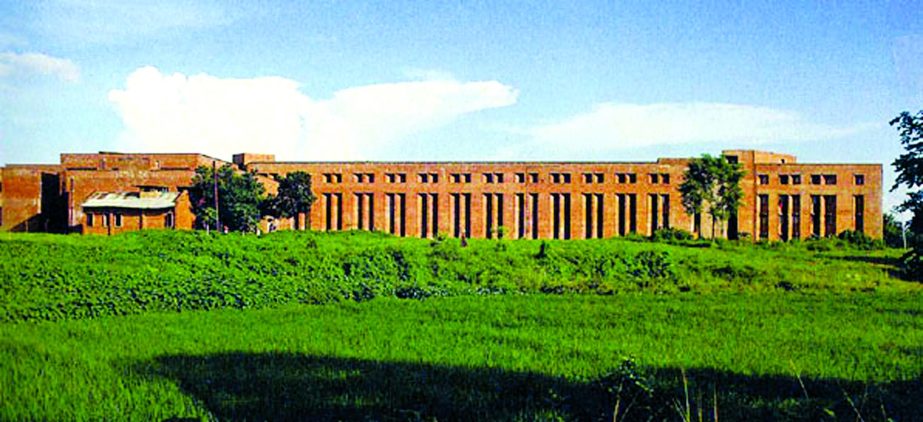

Interestingly, it is some of the work of much younger architects, which takes the ‘archaeological’ exploration of evocative types and complex formation to a new level of discourse. This is apparent in some of the work of Uttam Kumar Saha, and the offices of C.A.P.E. and Diagram. The S.O.S. Youth Village at Dhaka designed by C.A.P.E. (architects: Raziul Ahsan and Nahas Khalil), completed in 1984, and the more recent Hermann Gmeiner Social Centre at Khulna by Uttam Kumar Saha (of Consociates Ltd.), completed in 1987, both indicate a tentative beginning in this new direction. While the former is located on an urban site and the latter on a rural one, both the projects engage in similar strategies: fragmentation of volumes instead of a single, cubic monolith, and the resulting creation of contained exterior spaces. The permeability of the space, as in the uthan (courtyard) of traditional spatial organisation, forms a link with the public realm and allows pavilion-like settings for the individual volumes. Both projects are convincing responses to their geophysical location: the Dhaka project is consciously articulated, in its relationship to the street and in its formal ‘impurity,’ to play its (sub) urban role, and the Khulna project makes a most sensitive interjection in the idyllic Bengali landscape. Again, both the projects employ contemporary constructional means to form their specific roofscapes of remembered shapes.

While these small emerging architectural events promise a new water-shed in evolving a ‘place-evocative’ architectural strategy within contemporary conditions, more formidable issues remain to be confronted: how can architecture, as a profession and discipline, attain a more responsible role in this vulnerable land-water mass inhabited by an incredible number of people? While phenomenal rural exodus requires a closer scrutiny of unprecedented changes in the urban domain, how can the urban-based architects of Bangladesh focus their energies and services when nearly 80 per cent of the people still live in villages? How can architecture be socially responsive at all in the present political and economic instability engendered more than anything by a lack of collective vision? What immediate roles can, and should, architects play, given the range of resources available and political societal constraints, in order to confront the daunting dilemma of housing and organization of the human environment?

Muzharul Islam, as early as 1968, talked of the special task of architecture and architects in this critical situation: “When the activities of man eventuate in the creation of either natural or man-made objects on the surface of the earth, they become the concern of the architect. The architect’s traditional activities have been in the realm of small-scale structures, but he now feels that without rational and large-scale designing of physical space and objects, it is not possible for him to function fully even within his own discipline; He feels that it is through regional planning alone it is possible to change nature and create the most favorable conditions for his small scale activities.” It seems that the situation in Bangladesh, instead of relegating architecture to an elitist and peripheral role, demands precisely the total involvement of architects and in the broadest scope of visionary and architectural thinking. n

End…