Weekend Plus Desk :

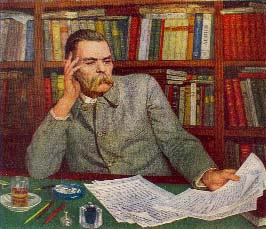

Aleksei Maksimovich Peshkov is better known as Maxim Gorky. He was a Russian author, a founder of the socialist realism literary method, and a political activist. Socialist realism, an approach that sought to be ‘realist in form’ and ‘socialist in content,’ became the basis for all Soviet art and made heroes of previously unheroic literary types, holding that the purpose of art was inherently political-to depict the ‘glorious struggle of the proletariat’ in its creation of Socialism.

Gorky was born in the city of Nizhny Novgorod, renamed Gorky in his honour during the Soviet era but restored to its original name following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1989. Gorky was something of an enigma, a revolutionary who was genuinely sympathetic to the underclass and who embraced the ethics and ideals of the revolution early on, but who had growing doubts about Lenin and the Bolsheviks following the 1917 Russian Revolution. Gorky’s legacy is inextricably linked with both the revolution and the literary movement, socialist realism that he helped to create.

From 1906 to 1913 and from 1921 to 1929, he lived abroad, mostly in Capri; after his return to the Soviet Union he reluctantly embraced the cultural policies of the time. Despite his belated support, he was not permitted to travel outside the country again.

Maxim Gorky was born on March 16, 1868, in the Volga River city of Nizhny Novgorod, Russian’s forth-largest city. Gorky lost his father when he was 4 years old and mother at age 11, and the boy was raised in harsh conditions by his maternal grandparents. His relations with his family members were strained. At one time Gorky even stabbed his abusive stepfather. Yet Gorky’s grandmother had a fondness for literature and compassion for the poor, which influenced the child. He left home at the age of 12 and began a series of occupations, as an errand boy, dishwasher on a steamer, and apprentice to an icon maker. During these youthful years Gorky witnessed the harsh, often cruel aspects of life for the underclass, impressions that would inform his later writings.Almost completely self-educated, Gorky tried unsuccessfully to enter the University of Kazan. For the next 6 years, he wandered widely about Russia, the Ukraine, and the Caucasus. After an attempt at suicide in December 1887, Gorky traveled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.

Gorky began writing under pseudonym (Jehudiel Khlamida), publishing stories and articles in newspapers of the Volga region. He began using the pseudonym Gorky (literally ‘bitter’) in 1892, while working for the Tiflis newspaper (The Caucasus). Gorky’s first book, a two-volume collection of his writings entitled (Essays and Stories) was published in 1898. It enjoyed great success, catapulting him to fame.

At the turn of the century, Gorky became associated with the Moscow Art Theater, which staged some of his plays. He also became affiliated with the Marxist journals Life and New Word and publicly opposed the Tsarist regime. Gorky befriended many revolutionary leaders, becoming Lenin’s personal friend after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press and was arrested numerous times. In 1902, Gorky was elected the honorary Academician of Literature, but Nicholas II ordered the annulment of this election. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy.

While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive Russian Revolution of 1905, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events. In 1905, he officially joined the ranks of the Bolshevik faction in the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. He left the country in 1906 to avoid arrest, traveling to America where he wrote his most famous novel, Mother.

He returned to Russia in 1913. During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, but his relations with the Communists turned sour. Two weeks after the October Revolution of 1917 he wrote: “Lenin and Trotsky don’t have any idea about freedom or human rights. They are already corrupted by dirty poison of the power, this is visible by their shameful disrespect of freedom of speech and all other civil liberties for which the democracy was fighting.” Lenin’s 1919 letters to Gorky contain threats: “My advice to you: Change your surroundings, your views, your actions, otherwise life may turn away from you.”

In August 1921, his friend, fellow writer, and poet Anna Akhmatova’s husband Nikolai Gumilyov was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka for his monarchist views. Gorky hurried to Moscow, attained the order to release Gumilyov from Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd found out that Gumilyov had already been shot. In October, Gorky emigrated to Italy on grounds of illness: He had contracted tuberculosis.

While Gorky had his struggles with the Soviet regime, he never entirely broke ranks. His exile had been self-imposed. But in Sorrento, Gorky found himself without money and without glory. He visited the USSR several times after 1929, and in 1932, Joseph Stalin personally invited him to return from emigration for good, an offer he accepted. In June 1929, Gorky visited Solovki (cleaned up for this occasion) and wrote a positive article about the Gulag camp that already had gained an ill reputation in the West. Gorky’s return from fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (currently the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in the suburbs. One of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, was renamed in his honor, in addition to the city of his birth.

In 1933, Gorky edited an infamous book about the Belomorkanal, presented as an example of the “successful rehabilitation of the former enemies of proletariat.”

He supported the First Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934 and Stalin’s policies in general. Yet, with the step-up of Stalinist repressions, especially after the death of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his Moscow house. The sudden death of his son Maxim Peshkov, in May 1935, was followed by his own in June 1936. Both died under mysterious circumstances, but speculation that they were poisoned has never been proven. Stalin and Molotov were among those who hand-carried Gorky’s coffin during his funeral.

During the Bukharin ‘show trial’ in 1938, one of the charges brought up was that Gorky was killed by Genrikh Yagoda’s NKVD agents.

Gorky’s city of birth was renamed back to Nizhny Novgorod in 1990.

Gorky was a major factor in the rapid rise of socialist realism and his pamphlet ‘On Socialist Realism’ essentially lays out the principles of Soviet art. Socialist realism held that successful art depicts and glorifies the proletariat’s struggle toward socialist progress. The Statute of the Union of Soviet Writers in 1934 stated that socialist realism is the basic method of Soviet literature and literary criticism. It demands of the artist the truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development. Moreover, the truthfulness and historical concreteness of the artistic representation of reality must be linked with the task of ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism.

Its purpose was to elevate the common factory or agricultural worker by presenting his life, work, and recreation as admirable. The ultimate aim was to create what Lenin called ‘an entirely new type of human being’: the New Soviet Man. Stalin described the practitioners of socialist realism as ‘engineers of souls.’

In some respects, the movement mirrors the course of American and Western art, where the common man and woman became the subject of the novel, the play, poetry, and art. The proletariat was at the center of communist ideals; hence, his life was a worthy subject for study. This was an important shift away from the aristocratic art produced under the Russian tsars of previous centuries, but had much in common with the late-19th century fashion for depicting the social life of the common people.

Compared to the psychological penetration and originality of 20th century Western art, socialist realism often resulted in a bland and predictable range of works, aesthetically often little more than political propaganda (indeed, Western critics wryly described the principles of Socialist realism as ‘girl meets tractor’). Painters would depict happy, muscular peasants and workers in factories and collective farms; during the Stalinist period, they also produced numerous heroic portraits of the dictator to serve his cult of personality. Industrial and agricultural landscapes were popular subjects, glorifying the achievements of the Soviet economy. Novelists were expected to produce uplifting stories infused with patriotic fervour for the state. Composers were to produce rousing, vivid music that reflected the life and struggles of the proletariat.

Socialist realism thus demanded close adherence to party doctrine, and has often been criticised as detrimental to the creation of true, unfettered art -or as being little more than a means to censor artistic expression. Czeslaw Milosz, writing in the introduction to Sinyavsky’s On Socialist Realism, describes the works of socialist realism as artistically inferior, a result necessarily proceeding from the limited view of reality permitted to creative artists.

Not all Marxists accepted the necessity of socialist realism. Its establishment as state doctrine in the 1930s had rather more to do with internal Communist Party politics than classic Marxist imperatives. The Hungarian Marxist essayist Georg Lukács criticized the rigidity of socialist realism, proposing his own ‘critical realism’ as an alternative. However, such voices were a rarity until the 1980s.

Gorky’s literary output is intimately bound up with the revolution and the artistic movement that he helped to found, yet is more subtle and descriptive than Soviet works during the Stalinist era. Gorky’s early stories sympathetically portrayed the derelicts and social outcasts of Russia in contrast to respectable, bourgeois society. His sympathy for the most marginalised made him known as a powerful spokesman for the Russian masses.

His novel, Mother, often considered the first work of socialist realism, would serve as example for later writers. It tells the story of the revolutionary transformation of Pavel Vlasov and his mother, Nilovna. Pavel’s story is fairly typical, a factory worker who becomes radicalised. But the story of his mother, Nilovna, is what gives the novel its centre. She represents the transition from simple, uneducated Christian to dedicated revolutionary. Timid and superstitious, she undergoes a process of enlightenment, with the valor born of conviction. The real hero of the novel is the revolution itself. The milieu is proletarian. Morality is determined by class. All representatives of the regime and upper class are corrupt and disgusting. The peasants are sympathetic but undisciplined. The proletarians are the moral force for positive change.

His best novels are the autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, In the World, and My University Years. (The title of the last novel ironically refers to the fact that Gorky was denied admission to Kazan University.) Gorky is at his best when recounting episodes from his own life. Once again the lower class milieu provides the backdrop for his reflections on pre-revolutionary life. Despite his uneasy relationship with the revolution, his work is inextricably linked to the real drama that unfolded in Russia after the turn of the century. Gorky’s fiction was notable for its realism and vitality, and was informed by a genuine passion for justice. His struggle to find a moral high ground within post-revolutionary society ultimately did not bear much fruit, and the ideals of justice he envisioned were silenced in a totalitarian political system that would exceed in injustice and inhumanity the reactionary monarchy it overthrew. n

Aleksei Maksimovich Peshkov is better known as Maxim Gorky. He was a Russian author, a founder of the socialist realism literary method, and a political activist. Socialist realism, an approach that sought to be ‘realist in form’ and ‘socialist in content,’ became the basis for all Soviet art and made heroes of previously unheroic literary types, holding that the purpose of art was inherently political-to depict the ‘glorious struggle of the proletariat’ in its creation of Socialism.

Gorky was born in the city of Nizhny Novgorod, renamed Gorky in his honour during the Soviet era but restored to its original name following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1989. Gorky was something of an enigma, a revolutionary who was genuinely sympathetic to the underclass and who embraced the ethics and ideals of the revolution early on, but who had growing doubts about Lenin and the Bolsheviks following the 1917 Russian Revolution. Gorky’s legacy is inextricably linked with both the revolution and the literary movement, socialist realism that he helped to create.

From 1906 to 1913 and from 1921 to 1929, he lived abroad, mostly in Capri; after his return to the Soviet Union he reluctantly embraced the cultural policies of the time. Despite his belated support, he was not permitted to travel outside the country again.

Maxim Gorky was born on March 16, 1868, in the Volga River city of Nizhny Novgorod, Russian’s forth-largest city. Gorky lost his father when he was 4 years old and mother at age 11, and the boy was raised in harsh conditions by his maternal grandparents. His relations with his family members were strained. At one time Gorky even stabbed his abusive stepfather. Yet Gorky’s grandmother had a fondness for literature and compassion for the poor, which influenced the child. He left home at the age of 12 and began a series of occupations, as an errand boy, dishwasher on a steamer, and apprentice to an icon maker. During these youthful years Gorky witnessed the harsh, often cruel aspects of life for the underclass, impressions that would inform his later writings.Almost completely self-educated, Gorky tried unsuccessfully to enter the University of Kazan. For the next 6 years, he wandered widely about Russia, the Ukraine, and the Caucasus. After an attempt at suicide in December 1887, Gorky traveled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.

Gorky began writing under pseudonym (Jehudiel Khlamida), publishing stories and articles in newspapers of the Volga region. He began using the pseudonym Gorky (literally ‘bitter’) in 1892, while working for the Tiflis newspaper (The Caucasus). Gorky’s first book, a two-volume collection of his writings entitled (Essays and Stories) was published in 1898. It enjoyed great success, catapulting him to fame.

At the turn of the century, Gorky became associated with the Moscow Art Theater, which staged some of his plays. He also became affiliated with the Marxist journals Life and New Word and publicly opposed the Tsarist regime. Gorky befriended many revolutionary leaders, becoming Lenin’s personal friend after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press and was arrested numerous times. In 1902, Gorky was elected the honorary Academician of Literature, but Nicholas II ordered the annulment of this election. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy.

While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive Russian Revolution of 1905, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events. In 1905, he officially joined the ranks of the Bolshevik faction in the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. He left the country in 1906 to avoid arrest, traveling to America where he wrote his most famous novel, Mother.

He returned to Russia in 1913. During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, but his relations with the Communists turned sour. Two weeks after the October Revolution of 1917 he wrote: “Lenin and Trotsky don’t have any idea about freedom or human rights. They are already corrupted by dirty poison of the power, this is visible by their shameful disrespect of freedom of speech and all other civil liberties for which the democracy was fighting.” Lenin’s 1919 letters to Gorky contain threats: “My advice to you: Change your surroundings, your views, your actions, otherwise life may turn away from you.”

In August 1921, his friend, fellow writer, and poet Anna Akhmatova’s husband Nikolai Gumilyov was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka for his monarchist views. Gorky hurried to Moscow, attained the order to release Gumilyov from Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd found out that Gumilyov had already been shot. In October, Gorky emigrated to Italy on grounds of illness: He had contracted tuberculosis.

While Gorky had his struggles with the Soviet regime, he never entirely broke ranks. His exile had been self-imposed. But in Sorrento, Gorky found himself without money and without glory. He visited the USSR several times after 1929, and in 1932, Joseph Stalin personally invited him to return from emigration for good, an offer he accepted. In June 1929, Gorky visited Solovki (cleaned up for this occasion) and wrote a positive article about the Gulag camp that already had gained an ill reputation in the West. Gorky’s return from fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (currently the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in the suburbs. One of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, was renamed in his honor, in addition to the city of his birth.

In 1933, Gorky edited an infamous book about the Belomorkanal, presented as an example of the “successful rehabilitation of the former enemies of proletariat.”

He supported the First Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934 and Stalin’s policies in general. Yet, with the step-up of Stalinist repressions, especially after the death of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his Moscow house. The sudden death of his son Maxim Peshkov, in May 1935, was followed by his own in June 1936. Both died under mysterious circumstances, but speculation that they were poisoned has never been proven. Stalin and Molotov were among those who hand-carried Gorky’s coffin during his funeral.

During the Bukharin ‘show trial’ in 1938, one of the charges brought up was that Gorky was killed by Genrikh Yagoda’s NKVD agents.

Gorky’s city of birth was renamed back to Nizhny Novgorod in 1990.

Gorky was a major factor in the rapid rise of socialist realism and his pamphlet ‘On Socialist Realism’ essentially lays out the principles of Soviet art. Socialist realism held that successful art depicts and glorifies the proletariat’s struggle toward socialist progress. The Statute of the Union of Soviet Writers in 1934 stated that socialist realism is the basic method of Soviet literature and literary criticism. It demands of the artist the truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development. Moreover, the truthfulness and historical concreteness of the artistic representation of reality must be linked with the task of ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism.

Its purpose was to elevate the common factory or agricultural worker by presenting his life, work, and recreation as admirable. The ultimate aim was to create what Lenin called ‘an entirely new type of human being’: the New Soviet Man. Stalin described the practitioners of socialist realism as ‘engineers of souls.’

In some respects, the movement mirrors the course of American and Western art, where the common man and woman became the subject of the novel, the play, poetry, and art. The proletariat was at the center of communist ideals; hence, his life was a worthy subject for study. This was an important shift away from the aristocratic art produced under the Russian tsars of previous centuries, but had much in common with the late-19th century fashion for depicting the social life of the common people.

Compared to the psychological penetration and originality of 20th century Western art, socialist realism often resulted in a bland and predictable range of works, aesthetically often little more than political propaganda (indeed, Western critics wryly described the principles of Socialist realism as ‘girl meets tractor’). Painters would depict happy, muscular peasants and workers in factories and collective farms; during the Stalinist period, they also produced numerous heroic portraits of the dictator to serve his cult of personality. Industrial and agricultural landscapes were popular subjects, glorifying the achievements of the Soviet economy. Novelists were expected to produce uplifting stories infused with patriotic fervour for the state. Composers were to produce rousing, vivid music that reflected the life and struggles of the proletariat.

Socialist realism thus demanded close adherence to party doctrine, and has often been criticised as detrimental to the creation of true, unfettered art -or as being little more than a means to censor artistic expression. Czeslaw Milosz, writing in the introduction to Sinyavsky’s On Socialist Realism, describes the works of socialist realism as artistically inferior, a result necessarily proceeding from the limited view of reality permitted to creative artists.

Not all Marxists accepted the necessity of socialist realism. Its establishment as state doctrine in the 1930s had rather more to do with internal Communist Party politics than classic Marxist imperatives. The Hungarian Marxist essayist Georg Lukács criticized the rigidity of socialist realism, proposing his own ‘critical realism’ as an alternative. However, such voices were a rarity until the 1980s.

Gorky’s literary output is intimately bound up with the revolution and the artistic movement that he helped to found, yet is more subtle and descriptive than Soviet works during the Stalinist era. Gorky’s early stories sympathetically portrayed the derelicts and social outcasts of Russia in contrast to respectable, bourgeois society. His sympathy for the most marginalised made him known as a powerful spokesman for the Russian masses.

His novel, Mother, often considered the first work of socialist realism, would serve as example for later writers. It tells the story of the revolutionary transformation of Pavel Vlasov and his mother, Nilovna. Pavel’s story is fairly typical, a factory worker who becomes radicalised. But the story of his mother, Nilovna, is what gives the novel its centre. She represents the transition from simple, uneducated Christian to dedicated revolutionary. Timid and superstitious, she undergoes a process of enlightenment, with the valor born of conviction. The real hero of the novel is the revolution itself. The milieu is proletarian. Morality is determined by class. All representatives of the regime and upper class are corrupt and disgusting. The peasants are sympathetic but undisciplined. The proletarians are the moral force for positive change.

His best novels are the autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, In the World, and My University Years. (The title of the last novel ironically refers to the fact that Gorky was denied admission to Kazan University.) Gorky is at his best when recounting episodes from his own life. Once again the lower class milieu provides the backdrop for his reflections on pre-revolutionary life. Despite his uneasy relationship with the revolution, his work is inextricably linked to the real drama that unfolded in Russia after the turn of the century. Gorky’s fiction was notable for its realism and vitality, and was informed by a genuine passion for justice. His struggle to find a moral high ground within post-revolutionary society ultimately did not bear much fruit, and the ideals of justice he envisioned were silenced in a totalitarian political system that would exceed in injustice and inhumanity the reactionary monarchy it overthrew. n