Chau Doan :

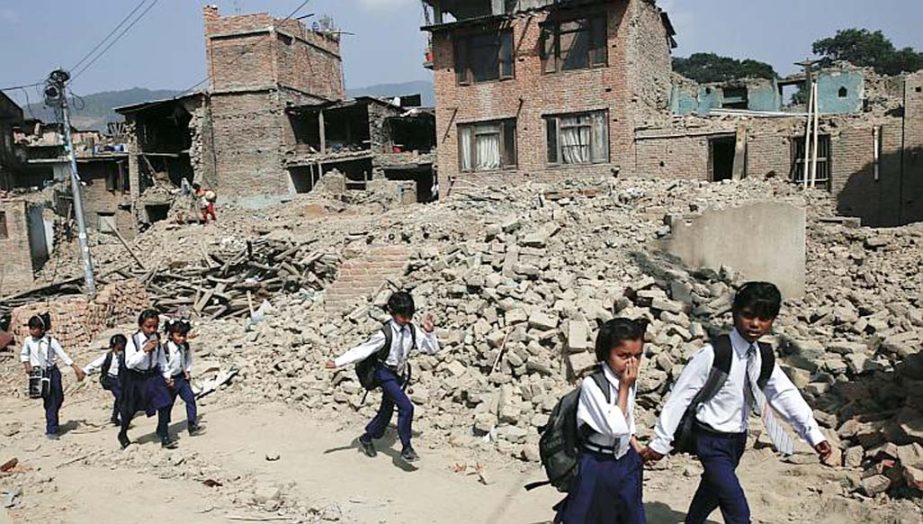

When the 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Nepal on April 25, it caused the total or partial collapse of more than 2,000 schools and damaged over 5,000 schools. The massive disruption caused by the earthquake and aftershocks on school infrastructure has reverberated into children’s development.

This tragedy is not an exception – each year natural disasters around the world have had devastating effects on children’s education. Typhoon Haiyan damaged more than 2,500 schools and affected 1.4 million children in the Philippines in 2013. The recent floods in Malawi affected hundreds of schools, disrupting the education of more than 350,000 children.

Over the last decade, multilateral and bilateral development finance institutions, United Nations agencies, and nongovernmental organizations have been engaged in efforts to make schools more resilient to disasters. Despite these efforts, the safety of schools in many disaster-prone countries is largely unknown, and governments and donors continue to finance new school construction without taking safety into account. In Nepal, for instance, poor enforcement of building standards and insufficient technical supervision had led to very poor construction practices in some areas and very vulnerable education buildings. This raises a number of questions:

Why are so many schools around the world vulnerable to the impact of natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes?

How have some countries managed to ensure the safety of students and teachers and to avoid disruption of educational services, while others have not?

What can be done to help countries adopt a systematic approach to ensuring school infrastructure safety?

The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) recently launched the Global Program for Safer Schools (GPSS) to help answer these questions, and better protect students in vulnerable countries.

This new initiative is working to ensure that school facilities and the communities they serve become more resilient to natural hazards by reducing the physical impact of disasters on school infrastructure. The initiative works with ministries of finance, public works, and education, to integrate risk considerations into new and existing education investments to increase resilience on a large scale.

The problem of unsafe schools requires concerted and sustained efforts by many partners. To address it, the GPSS collaborates with a wide range of international partners, including United Nations agencies such as UNICEF, UNESCO, and UNISDR; international NGOs such as Save the Children; and private sector companies such as Arup.

In this context, the program is developing an open source mapping platform to provide a global baseline of all school communities and facilities at risk, and a measure of progress towards global school safety.

The program recently hosted a technical workshop to share experiences from across the world and to explore how governments can address the challenges related to promoting the safety of school infrastructure. The event, held in partnership with the World Bank-GFDRR Tokyo Disaster Risk Management Hub, brought together technical experts and policy makers from Armenia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Mongolia, Peru, and Turkey. Participants concluded that improved risk information, and a greater understanding of the institutional and technical processes for school construction are the foundation for increasing the resilience of schools.

“Through a detailed disaster risk analysis, we discovered that by improving the physical safety of 600 schools, which amounts to 30 percent of our total school building stock, we can reduce about 70 percent of the seismic risk in the capital city of Lima,” said Adela Cáceres Del Carpio, Director of Planning, Ministry of Education, Peru.

Authorities from the City of Istanbul, Turkey, also shared how they have been able to strengthen 944 schools, thereby ensuring the safety of more than 1.5 million students. “The development of prioritization criteria was essential for the investment in school resilience in Istanbul, providing transparency and informing which schools we had to target,” said Fikret Azili, deputy director of the Istanbul Project Coordination Unit. “The result was significant improvements in the overall learning environment by increasing the number of classrooms from 4,310 to 7,579, which reduced the number of children per classroom significantly.”

Over the course of the two-day workshop, technical experts and policymakers agreed that city and national school safety programs must incorporate the following core elements to achieve success:

Developing a national school infrastructure inventory is essential for any long-term strategy for infrastructure safety. A school infrastructure census can provide insight into the potential magnitude of rehabilitation needs to reduce existing risk in the education sector.

A physical risk assessment of school infrastructure should help prioritize investments to strengthen school infrastructure. A physical risk assessment of schools provides an estimation of the magnitude and frequency of potential damages and losses. It also enables the identification of the most vulnerable schools.

Strategies for new construction should build on an institutional and technical assessment of the current school construction environment. Understanding what factors are driving unsafe construction practices will enable decision-makers to make targeted adjustments to planned investments to ensure the quality of new construction and avoid the creation of new risk.

With early successes on programs like Peru, GPSS and its partners are well-positioned to help make global education more resilient to climate and disaster risk. Moving forward, safer school activities will start in Armenia, El Salvador, Jamaica, Mozambique, the Pacific, and the Philippines with contributions from Australia, Japan, and other donors.

– World Bank story

When the 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Nepal on April 25, it caused the total or partial collapse of more than 2,000 schools and damaged over 5,000 schools. The massive disruption caused by the earthquake and aftershocks on school infrastructure has reverberated into children’s development.

This tragedy is not an exception – each year natural disasters around the world have had devastating effects on children’s education. Typhoon Haiyan damaged more than 2,500 schools and affected 1.4 million children in the Philippines in 2013. The recent floods in Malawi affected hundreds of schools, disrupting the education of more than 350,000 children.

Over the last decade, multilateral and bilateral development finance institutions, United Nations agencies, and nongovernmental organizations have been engaged in efforts to make schools more resilient to disasters. Despite these efforts, the safety of schools in many disaster-prone countries is largely unknown, and governments and donors continue to finance new school construction without taking safety into account. In Nepal, for instance, poor enforcement of building standards and insufficient technical supervision had led to very poor construction practices in some areas and very vulnerable education buildings. This raises a number of questions:

Why are so many schools around the world vulnerable to the impact of natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes?

How have some countries managed to ensure the safety of students and teachers and to avoid disruption of educational services, while others have not?

What can be done to help countries adopt a systematic approach to ensuring school infrastructure safety?

The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) recently launched the Global Program for Safer Schools (GPSS) to help answer these questions, and better protect students in vulnerable countries.

This new initiative is working to ensure that school facilities and the communities they serve become more resilient to natural hazards by reducing the physical impact of disasters on school infrastructure. The initiative works with ministries of finance, public works, and education, to integrate risk considerations into new and existing education investments to increase resilience on a large scale.

The problem of unsafe schools requires concerted and sustained efforts by many partners. To address it, the GPSS collaborates with a wide range of international partners, including United Nations agencies such as UNICEF, UNESCO, and UNISDR; international NGOs such as Save the Children; and private sector companies such as Arup.

In this context, the program is developing an open source mapping platform to provide a global baseline of all school communities and facilities at risk, and a measure of progress towards global school safety.

The program recently hosted a technical workshop to share experiences from across the world and to explore how governments can address the challenges related to promoting the safety of school infrastructure. The event, held in partnership with the World Bank-GFDRR Tokyo Disaster Risk Management Hub, brought together technical experts and policy makers from Armenia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Mongolia, Peru, and Turkey. Participants concluded that improved risk information, and a greater understanding of the institutional and technical processes for school construction are the foundation for increasing the resilience of schools.

“Through a detailed disaster risk analysis, we discovered that by improving the physical safety of 600 schools, which amounts to 30 percent of our total school building stock, we can reduce about 70 percent of the seismic risk in the capital city of Lima,” said Adela Cáceres Del Carpio, Director of Planning, Ministry of Education, Peru.

Authorities from the City of Istanbul, Turkey, also shared how they have been able to strengthen 944 schools, thereby ensuring the safety of more than 1.5 million students. “The development of prioritization criteria was essential for the investment in school resilience in Istanbul, providing transparency and informing which schools we had to target,” said Fikret Azili, deputy director of the Istanbul Project Coordination Unit. “The result was significant improvements in the overall learning environment by increasing the number of classrooms from 4,310 to 7,579, which reduced the number of children per classroom significantly.”

Over the course of the two-day workshop, technical experts and policymakers agreed that city and national school safety programs must incorporate the following core elements to achieve success:

Developing a national school infrastructure inventory is essential for any long-term strategy for infrastructure safety. A school infrastructure census can provide insight into the potential magnitude of rehabilitation needs to reduce existing risk in the education sector.

A physical risk assessment of school infrastructure should help prioritize investments to strengthen school infrastructure. A physical risk assessment of schools provides an estimation of the magnitude and frequency of potential damages and losses. It also enables the identification of the most vulnerable schools.

Strategies for new construction should build on an institutional and technical assessment of the current school construction environment. Understanding what factors are driving unsafe construction practices will enable decision-makers to make targeted adjustments to planned investments to ensure the quality of new construction and avoid the creation of new risk.

With early successes on programs like Peru, GPSS and its partners are well-positioned to help make global education more resilient to climate and disaster risk. Moving forward, safer school activities will start in Armenia, El Salvador, Jamaica, Mozambique, the Pacific, and the Philippines with contributions from Australia, Japan, and other donors.

– World Bank story