Life Desk :

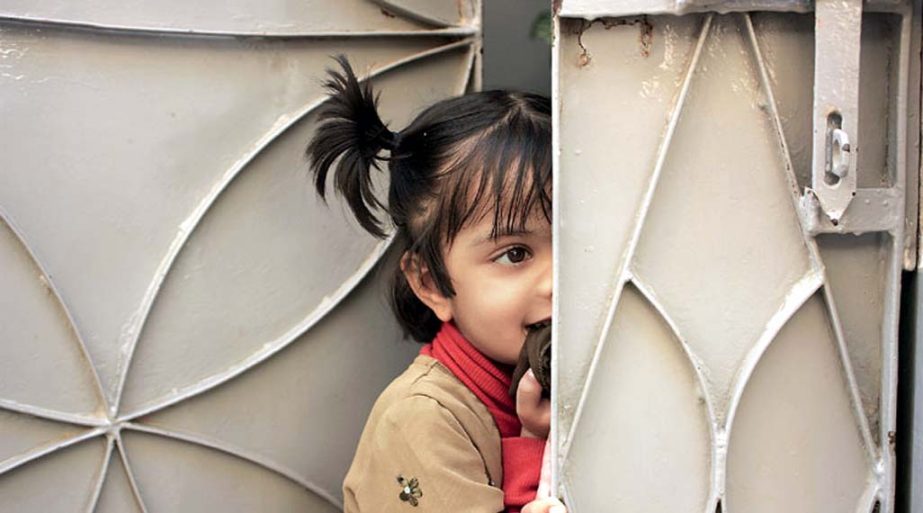

We are sauntering along just fine, talking about what dogs do when they go to school and if they also like chocolate ice cream, when That Question waylays us. It sends my three-year-old daughter scurrying behind my back, from where she warily eyes the neighbour and refuses all conversation, including a hello. Usually, I mumble an explanation, today, I smile and walk away, much to the little one’s relief.

I am a mother to a shy child. Sometimes, it can be a lonely space to be. When other children run in high spirits at the playground, she chooses to hang back, watching them in fascination. While they confidently walk up to adults and demand their indulgence, she shrinks back in fear. The world seems often to overwhelm our child even as she delights in it.

The world has little empathy for those who hold themselves back. If you are a child slow to open up, it wants to hurry you up. If you clam shut, it insists on prising you out of your shell. Neighbours cluck-cluck in disapproval and bemoan old days when large families cured such deviant behaviour. At a play school we once went to, the teacher watched my daughter refuse a toffee for the third time and said, “Send her here and I will make your child an extrovert.”

We never went back. But it was clear: our child did not fit in.

Nevertheless, we blamed ourselves. We had grown up amid brothers and sisters and cousins, in houses where the door was always open to the neighbour who dropped by, in mohallas and paras where one made friends for life. We looked at her life in a cold city – a child growing up in a solitary flat, with the nanny for company, and sometimes her grandparents – and found it wanting. It’s not her, we thought. It’s the life we have made for ourselves. We had forgotten that despite a safety net of people, neither of us had turned out gregarious.

Why do we find it uncomfortable to deal with shy people? Perhaps, it snaps our cosy belief in the inevitability and effortlessness of human connection. A shy child, especially, reminds you of the time, patience and hard work involved in that fussy business of making friends – and keeping them.

But not a little of our fears have to do with rearing our children to aim for – and find – success. When it comes down to it, all attitudes of parenting, from helicopter-mom love to healthy neglect, are about shaping our children to face the world (if you have been to enough PTMs, you of course know, that ain’t enough: you’ve got to conquer it.) Introverted children – with their reluctance to draw attention to themselves, their need for alone time to recharge themselves – never seem to be the stuff of conquerors.

America is a prime example of a society that worships success and pathologises introversion. In her fascinating book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, Susan Cain traces the roots of this aversion to the early years of the 20th century, when America transformed from a largely agricultural economy to an industrial one, and when people began to live in cities where the codes of social life were rather mystifying. “The new economy called for a new kind of man – a salesman, a social operator, someone with a ready smile, a masterful handshake, and the ability to get along with colleagues while simultaneously outshining them.”

Does that sounded eerily familiar? That is because it is all around us. The respect Indians have had for geeks, nerds and the socially awkward is giving way to a fascination for the guy who can outshine a room full of talent by smooth talk, who can power his way to scholarships and promotion by the force of his personality. It reflects the great anxiety in professions about visibility: do we know the rules of networking? Were we seen and heard while we were working? It is a concern that filters down to schools and playgrounds, and our fears that a less outgoing child may fall behind – her role in the school skit may be shorter than others, her teachers might never discover her strengths because she does not speak up.

Cain’s book is a manifesto for the introverted life. It argues that by embracing the extrovert ideal – of sociability, public speaking – we ought not to neglect the strengths that come from a more interior life: reflection, deep and complex thought, creativity and the ability to break free of the herd. It urges teachers and schools not to treat introversion as something that needs to be cured, not just ask a quiet child to come out of her shell but think of her as having a “different learning style”, and to allow children to respond through written as well as vocal interventions.

Eventually, we found a nursery school that let our child be, without trying to turn her into what she is not. While she loves going to school, she remains a quiet child in class, one who delights in the antics of her classmates even if she does not join them, who observes life with a furious, if hidden, curiosity.

The hardest part once was the realisation that no one got to know the girl she is: funny and curious, in love with music and dance, creator of her own ulta-pulta language, a wild monkey through the day, intent puzzle-solver by evening. Over time, I have learnt to treasure her secret self, hoard it from the eyes of the world. I know that she will never be good at first impressions but I am sure she will find her own way through life, and on her own quiet terms.

There will be a next time when someone asks me, “why doesn’t she talk?” The answer to that question will be what my friend, who hid behind her mother all through her childhood, and is now a confident, voluble woman, said: because she listens.

Courtesy – Indian Express

We are sauntering along just fine, talking about what dogs do when they go to school and if they also like chocolate ice cream, when That Question waylays us. It sends my three-year-old daughter scurrying behind my back, from where she warily eyes the neighbour and refuses all conversation, including a hello. Usually, I mumble an explanation, today, I smile and walk away, much to the little one’s relief.

I am a mother to a shy child. Sometimes, it can be a lonely space to be. When other children run in high spirits at the playground, she chooses to hang back, watching them in fascination. While they confidently walk up to adults and demand their indulgence, she shrinks back in fear. The world seems often to overwhelm our child even as she delights in it.

The world has little empathy for those who hold themselves back. If you are a child slow to open up, it wants to hurry you up. If you clam shut, it insists on prising you out of your shell. Neighbours cluck-cluck in disapproval and bemoan old days when large families cured such deviant behaviour. At a play school we once went to, the teacher watched my daughter refuse a toffee for the third time and said, “Send her here and I will make your child an extrovert.”

We never went back. But it was clear: our child did not fit in.

Nevertheless, we blamed ourselves. We had grown up amid brothers and sisters and cousins, in houses where the door was always open to the neighbour who dropped by, in mohallas and paras where one made friends for life. We looked at her life in a cold city – a child growing up in a solitary flat, with the nanny for company, and sometimes her grandparents – and found it wanting. It’s not her, we thought. It’s the life we have made for ourselves. We had forgotten that despite a safety net of people, neither of us had turned out gregarious.

Why do we find it uncomfortable to deal with shy people? Perhaps, it snaps our cosy belief in the inevitability and effortlessness of human connection. A shy child, especially, reminds you of the time, patience and hard work involved in that fussy business of making friends – and keeping them.

But not a little of our fears have to do with rearing our children to aim for – and find – success. When it comes down to it, all attitudes of parenting, from helicopter-mom love to healthy neglect, are about shaping our children to face the world (if you have been to enough PTMs, you of course know, that ain’t enough: you’ve got to conquer it.) Introverted children – with their reluctance to draw attention to themselves, their need for alone time to recharge themselves – never seem to be the stuff of conquerors.

America is a prime example of a society that worships success and pathologises introversion. In her fascinating book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, Susan Cain traces the roots of this aversion to the early years of the 20th century, when America transformed from a largely agricultural economy to an industrial one, and when people began to live in cities where the codes of social life were rather mystifying. “The new economy called for a new kind of man – a salesman, a social operator, someone with a ready smile, a masterful handshake, and the ability to get along with colleagues while simultaneously outshining them.”

Does that sounded eerily familiar? That is because it is all around us. The respect Indians have had for geeks, nerds and the socially awkward is giving way to a fascination for the guy who can outshine a room full of talent by smooth talk, who can power his way to scholarships and promotion by the force of his personality. It reflects the great anxiety in professions about visibility: do we know the rules of networking? Were we seen and heard while we were working? It is a concern that filters down to schools and playgrounds, and our fears that a less outgoing child may fall behind – her role in the school skit may be shorter than others, her teachers might never discover her strengths because she does not speak up.

Cain’s book is a manifesto for the introverted life. It argues that by embracing the extrovert ideal – of sociability, public speaking – we ought not to neglect the strengths that come from a more interior life: reflection, deep and complex thought, creativity and the ability to break free of the herd. It urges teachers and schools not to treat introversion as something that needs to be cured, not just ask a quiet child to come out of her shell but think of her as having a “different learning style”, and to allow children to respond through written as well as vocal interventions.

Eventually, we found a nursery school that let our child be, without trying to turn her into what she is not. While she loves going to school, she remains a quiet child in class, one who delights in the antics of her classmates even if she does not join them, who observes life with a furious, if hidden, curiosity.

The hardest part once was the realisation that no one got to know the girl she is: funny and curious, in love with music and dance, creator of her own ulta-pulta language, a wild monkey through the day, intent puzzle-solver by evening. Over time, I have learnt to treasure her secret self, hoard it from the eyes of the world. I know that she will never be good at first impressions but I am sure she will find her own way through life, and on her own quiet terms.

There will be a next time when someone asks me, “why doesn’t she talk?” The answer to that question will be what my friend, who hid behind her mother all through her childhood, and is now a confident, voluble woman, said: because she listens.

Courtesy – Indian Express