Moniruddin Yusuf :

Bengal borrowed different systems of education and learning from Iran. We propose here to see the extensive influence of Iranian literatures and her poets in Bangladesh. Poetry and literary tradition that Iran left for us as a heritage, was more important than any other single factor in the field of culture. This tradition penetrated through the entire population of Bengal irrespective of high and low polished and boorish. Iranian literature sophisticated the Bengali people whether they are educated or uneducated to the extent that even a rural agriculturist or a small trader or a peddler could own the finest human sentiment and be aesthetically uplifted alike.

The reason for this extensive influence of Iranian literature was its correspondence with the advent of Islam. When Islam entered Bengal, this part of the sub-continent had no national language. The dialect spoken by the local people of Bangladesh was looked down upon by the ruling Brahmanical class. And so it was not sufficiently developed to contain any high thought or noble sentiment.

Equality of man and the Oneness of the Deity preached by Islam, presented an ideal that made the people of Bengal taste a culture befitting humanity. On that stage of development Iranian poetry and literature were ready for the consumption of Bengali people. In this way the start of our cultural commerce began with Iran. We were fortunate enough to have our language in such a formative stage that Iran could not but serve our purpose so amply and so nicely.

During the years of eleventh century, Iranian poetry entered the sphere of Anwari and Firdousi and by the next two centuries poets like Nizami, Omar Khaiyam and Sa’di lived and worked there. Muslims conquered Bengal in the thirteenth century A.D. and the influx of their coming remained unhindered for centuries hence.

From the very beginning, Muslim rulers and their followers patronized the education in Bengal. Imported centers of education were established in Lacknowti, Pandua, Darasbari, Rangpur, Chittagong, Sylhet and Sonargaon. It is told that in Bengal, a self supporting madrassa did not exist.

Education and learning are basements for erecting the edifice of aesthetic structures. The strong basements were the practical lives that held in enduring edifices. Muslims of Bangal, through education, fortified their cultural life and prepared themselves for absorbing the influence of Iranian literature.

The spirit of Islam preached by Sufis and Sufi poets of Iran formed the conventional society in Bengal. The great Hindu poet Chandidas wrote lines edifying the dignity of man in his verses, the like of which were not to be found in Hindu literature. This spirit of the dignity of man was contagious for the Baishnavas and Baishnava poets alike.

Stories concerning the worship and adoration of Gods and Goddesses were gradually supplanted by sorrows and happiness of practical man. Human interest grew in Bengali literature through the transitions and adaptations of Iranian literature. First of this kind was ‘Yusuf-Zuleikha’ by Shah Muhammad Saghir. ‘Yusuf-Zuleikha’ was written by Poet Firdousi. The story of Yusuf was taken from the Quran. The Quran terms it as the most beautiful story. Restraint of a practical man and Prophet Yusuf is the central theme of the story. Quran does not name the heroine of the story as Zuleikha. She was termed as ‘Imratul Aziz’.

One of the most powerful writers of the Bengali medieval period was Daulat Qazi. He wrote a romantic episodic poetry named ‘Lor Chondrani’. The story element of that book was taken from Hindi. This was nothing but the imitation of human interest in episode that was practiced by Iranian stalwarts like Nizami and others. Story of Lor Chondrani is this:

King of Gohari, Lor had a beautiful consort named Moinamoti. Husband and wife were happy. One day a traveling mendicant appeared. He showed the king Lor a portrait of princess Chondrani and informed the king that the princess was not unmarried but her husband was a hermaphrodite. The princess absolutely deserved the king. At the words of mendicant, Lor was so amorous that he left for Mohradesh to gain Chondrani. Lor fought with the hermaphrodite husband of Chondrali and defeated him. The desired union of Lor-Chondrani happened. Lor passed time in Mohradesh with princess Chondrani. In this side a son of the neighboring king heard the physical and mental beauty of Mainamati and sent panderers to enchant her. The panderers tried her best, but Mainamati did not agree to the proposal. So sent a parrot with the help of a Brahmin to Lor. With the dexterity of the Brahmin and the message delivered by the parrot, the bye gone memory of Lor reappeared. King Lor returned with Chondrani to Moinamati bearing the kingdom to his son. Reunion of Lor occurred with Moinamati.

This was the etnsodic beauty of Sufistic Iran. The real Sufism is not against the spirit of Islam. So, Lor returned to his previous lawful wife with Chondrani, the second lawful wife. He did not leave her there. Muslim, in the spiritual advancement, should not give up his lawful earthy possessions.

It is to be remembered that on the rural poets of Bengal the direct influence of Iranian literature was not possible. The influence generated through the cultural sphere of the Muslim society. So, in rural episodic poetry Gods and Goddesses did not generate pathetic origination. Instead, man and woman played their parts humanly. Realistic tendency entered the story-element of Bengali poetry. We experienced in Bengali literature the current stream of events. The sixteenth century poet Mukundram Chakraborty wrote in his ‘Chondi Mongol’ the current lives of Hindu-Muslim societies. His realistic delimitation was an indirect influence of practical ways of life scattered by the Muslims all around.

Stories of ‘Mymensingh Geetika’ and ‘Purbo Bongo Geetika’ were written from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. The episodic poetries were written by Hindus and Muslims alike.

Dr Dinesh Chandra Sen in the introductory words of his valuable collection of ‘Mymensingh Geetika’ writes, the reign of eastern Mymensingh from the ancient Sena dynasty was out of the reach of Brahmanical order. So in the episodes of seventeenth and even the eighteenth centuries, we do not find any influence of Brahmanical or Sanskrit imitation. This region was not like other areas of Bengal. The rigidity of fanatic scriptures could not bind the women folk of this area and therefore we find in these ‘Geetikas’ the heroines are open minded and practically free and their romantic love so deep and humane.

Dr Sen is very true in his remarks. But the reason he mention is not so correct. It was not the absence of the rigidity of Brahmanical scripture that made the woman folk of that region so affectionate and romantically so deep and impregnated with imaginative faculties. The episodes of ‘Geetika’ were out and out human. They are of the same family of Iranian romances of ‘Shireen Khosru,’ ‘Laila Mojnoon’ and others.

One of the tragic episodes of ‘Geetika’ is known as ‘Mohua.’ The French novelist Romain Rolland has spoken very highly of it.

The story narrates a band of gypsy men and women roamed about and used to exhibit circus shows. Among them Mahua was a very beautiful girl, who could show exquisite physical exercises within the circus.

One day the band of gypsies arrived at a village where a rich Brahmin family lived. The leader of the gypsy group Homra asked the permission of the mother of the Brahmin to show the circus.

Being permitted, Homra asked his band to start the show. The physical exercise of Mohua enchanted the young Brahmin, Nadiarchand. He gave the gypsies various gifts and at the end helped them to own houses with plots of land. The gypsies were glad and they lived there happily.

One day in the evening Nadiarchand saw Mohua coming back after performing show business and asked her to see him next at the bathing ghat alone at dusk. Next day, Mahua kept her words and went to the particular place in an appointed time to see the Brahmin.

The dialogue between hero and heroine on the bathing ghat was so enchanting that this crude and indigenous background caused anyone to forget the whereabouts and aesthetically roused him to a high level of romantic love.

Here asks Mohua: ‘(Oh, the beautiful damsel, you are fetching water in your pitcher. Do you remember what I told you yesterday?

Mahua replies: Hear oh Youngman of foreign land, hear me, What did you say yesterday, I do not remember.

Nadiarchand retorts: Oh! damsel of coming age, your mind is prone to forgetfulness. So, you have forgotten in a night a weighty word conveyed to you.

Mohua answers with her head down: Oh! you are a foreign man and I am a different woman, I die in shamefulness to talk to you.

Nadiarchand consoles Mohua and ensure her of the situation: Filling your pitcher oh beautiful damsel and rippling water with it, Shy don’t you talk with smiling face; there is none here with me.

And Nadiarchand asks the acquaintance of the girl: Who is your mother, girl, and who is your father, where had you been since you came here?

Mohua expresses her helplessness and unfamiliarity and replies: I have no mother and father, no brother born of the same mother, I am a moss in the stream and go on over afloat. And then Mohua relates her own circumstances to Nadiarchand: It was predestined, so I roam about with the gypsies, and bum myself with the flame of mine.

There is no sympathetic soul in this country to whom should I express myself.

Say, who will realize the grief of my burning heart? Oh the young Brahmin, you are happily turning with your beautiful consort. In your own house, the condition congenial to you. The Brahmin says, oh the virgin. you are stone hearted, you utter a lie, I am not yet married.

Mohua retorts: Your parents are hard-hearted and you too are stone, so, much a youthful time of life passes in vain.

Yes, my parents are hard-hearted and myself too is so, If I get a bride like you, I do it instantly.

Oh, shameless Brahmin, you are devoid of any bashfulness, Let the person die with the pitcher entangled in your neck. Oh, the beautiful bride, where should I get pitcher and where to find rope, You yourself become deep river and I plunge to die into your water.

Before we proceed to tragic consequences of the story, let us see this romantic situation of an episode of ‘Shahnama’ by Firdausi and compare the similarity of effect produced there aesthetically.

Hero of the episode of Shahnama, Zal has come to see Rudaba in a moonlit night. From a lofty balcony Rudaba announced felicitation for Zal. The hero with the name of ‘Yazdan’ expresses his legitimate hope: I pray that God in His bounty show me your face in seclusion. Valiant Zal asks Rudaba how he will ascend the high rampart and reach her.

Skillful Rudaba causes to bring down her long tress as a ladder to be climbed by Zal, Rudaba asks: Now quickly come and gird up your loves one and try yourself with thy lions valour and claws of Kayani strength.

Contd on page 9

Bengal borrowed different systems of education and learning from Iran. We propose here to see the extensive influence of Iranian literatures and her poets in Bangladesh. Poetry and literary tradition that Iran left for us as a heritage, was more important than any other single factor in the field of culture. This tradition penetrated through the entire population of Bengal irrespective of high and low polished and boorish. Iranian literature sophisticated the Bengali people whether they are educated or uneducated to the extent that even a rural agriculturist or a small trader or a peddler could own the finest human sentiment and be aesthetically uplifted alike.

The reason for this extensive influence of Iranian literature was its correspondence with the advent of Islam. When Islam entered Bengal, this part of the sub-continent had no national language. The dialect spoken by the local people of Bangladesh was looked down upon by the ruling Brahmanical class. And so it was not sufficiently developed to contain any high thought or noble sentiment.

Equality of man and the Oneness of the Deity preached by Islam, presented an ideal that made the people of Bengal taste a culture befitting humanity. On that stage of development Iranian poetry and literature were ready for the consumption of Bengali people. In this way the start of our cultural commerce began with Iran. We were fortunate enough to have our language in such a formative stage that Iran could not but serve our purpose so amply and so nicely.

During the years of eleventh century, Iranian poetry entered the sphere of Anwari and Firdousi and by the next two centuries poets like Nizami, Omar Khaiyam and Sa’di lived and worked there. Muslims conquered Bengal in the thirteenth century A.D. and the influx of their coming remained unhindered for centuries hence.

From the very beginning, Muslim rulers and their followers patronized the education in Bengal. Imported centers of education were established in Lacknowti, Pandua, Darasbari, Rangpur, Chittagong, Sylhet and Sonargaon. It is told that in Bengal, a self supporting madrassa did not exist.

Education and learning are basements for erecting the edifice of aesthetic structures. The strong basements were the practical lives that held in enduring edifices. Muslims of Bangal, through education, fortified their cultural life and prepared themselves for absorbing the influence of Iranian literature.

The spirit of Islam preached by Sufis and Sufi poets of Iran formed the conventional society in Bengal. The great Hindu poet Chandidas wrote lines edifying the dignity of man in his verses, the like of which were not to be found in Hindu literature. This spirit of the dignity of man was contagious for the Baishnavas and Baishnava poets alike.

Stories concerning the worship and adoration of Gods and Goddesses were gradually supplanted by sorrows and happiness of practical man. Human interest grew in Bengali literature through the transitions and adaptations of Iranian literature. First of this kind was ‘Yusuf-Zuleikha’ by Shah Muhammad Saghir. ‘Yusuf-Zuleikha’ was written by Poet Firdousi. The story of Yusuf was taken from the Quran. The Quran terms it as the most beautiful story. Restraint of a practical man and Prophet Yusuf is the central theme of the story. Quran does not name the heroine of the story as Zuleikha. She was termed as ‘Imratul Aziz’.

One of the most powerful writers of the Bengali medieval period was Daulat Qazi. He wrote a romantic episodic poetry named ‘Lor Chondrani’. The story element of that book was taken from Hindi. This was nothing but the imitation of human interest in episode that was practiced by Iranian stalwarts like Nizami and others. Story of Lor Chondrani is this:

King of Gohari, Lor had a beautiful consort named Moinamoti. Husband and wife were happy. One day a traveling mendicant appeared. He showed the king Lor a portrait of princess Chondrani and informed the king that the princess was not unmarried but her husband was a hermaphrodite. The princess absolutely deserved the king. At the words of mendicant, Lor was so amorous that he left for Mohradesh to gain Chondrani. Lor fought with the hermaphrodite husband of Chondrali and defeated him. The desired union of Lor-Chondrani happened. Lor passed time in Mohradesh with princess Chondrani. In this side a son of the neighboring king heard the physical and mental beauty of Mainamati and sent panderers to enchant her. The panderers tried her best, but Mainamati did not agree to the proposal. So sent a parrot with the help of a Brahmin to Lor. With the dexterity of the Brahmin and the message delivered by the parrot, the bye gone memory of Lor reappeared. King Lor returned with Chondrani to Moinamati bearing the kingdom to his son. Reunion of Lor occurred with Moinamati.

This was the etnsodic beauty of Sufistic Iran. The real Sufism is not against the spirit of Islam. So, Lor returned to his previous lawful wife with Chondrani, the second lawful wife. He did not leave her there. Muslim, in the spiritual advancement, should not give up his lawful earthy possessions.

It is to be remembered that on the rural poets of Bengal the direct influence of Iranian literature was not possible. The influence generated through the cultural sphere of the Muslim society. So, in rural episodic poetry Gods and Goddesses did not generate pathetic origination. Instead, man and woman played their parts humanly. Realistic tendency entered the story-element of Bengali poetry. We experienced in Bengali literature the current stream of events. The sixteenth century poet Mukundram Chakraborty wrote in his ‘Chondi Mongol’ the current lives of Hindu-Muslim societies. His realistic delimitation was an indirect influence of practical ways of life scattered by the Muslims all around.

Stories of ‘Mymensingh Geetika’ and ‘Purbo Bongo Geetika’ were written from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. The episodic poetries were written by Hindus and Muslims alike.

Dr Dinesh Chandra Sen in the introductory words of his valuable collection of ‘Mymensingh Geetika’ writes, the reign of eastern Mymensingh from the ancient Sena dynasty was out of the reach of Brahmanical order. So in the episodes of seventeenth and even the eighteenth centuries, we do not find any influence of Brahmanical or Sanskrit imitation. This region was not like other areas of Bengal. The rigidity of fanatic scriptures could not bind the women folk of this area and therefore we find in these ‘Geetikas’ the heroines are open minded and practically free and their romantic love so deep and humane.

Dr Sen is very true in his remarks. But the reason he mention is not so correct. It was not the absence of the rigidity of Brahmanical scripture that made the woman folk of that region so affectionate and romantically so deep and impregnated with imaginative faculties. The episodes of ‘Geetika’ were out and out human. They are of the same family of Iranian romances of ‘Shireen Khosru,’ ‘Laila Mojnoon’ and others.

One of the tragic episodes of ‘Geetika’ is known as ‘Mohua.’ The French novelist Romain Rolland has spoken very highly of it.

The story narrates a band of gypsy men and women roamed about and used to exhibit circus shows. Among them Mahua was a very beautiful girl, who could show exquisite physical exercises within the circus.

One day the band of gypsies arrived at a village where a rich Brahmin family lived. The leader of the gypsy group Homra asked the permission of the mother of the Brahmin to show the circus.

Being permitted, Homra asked his band to start the show. The physical exercise of Mohua enchanted the young Brahmin, Nadiarchand. He gave the gypsies various gifts and at the end helped them to own houses with plots of land. The gypsies were glad and they lived there happily.

One day in the evening Nadiarchand saw Mohua coming back after performing show business and asked her to see him next at the bathing ghat alone at dusk. Next day, Mahua kept her words and went to the particular place in an appointed time to see the Brahmin.

The dialogue between hero and heroine on the bathing ghat was so enchanting that this crude and indigenous background caused anyone to forget the whereabouts and aesthetically roused him to a high level of romantic love.

Here asks Mohua: ‘(Oh, the beautiful damsel, you are fetching water in your pitcher. Do you remember what I told you yesterday?

Mahua replies: Hear oh Youngman of foreign land, hear me, What did you say yesterday, I do not remember.

Nadiarchand retorts: Oh! damsel of coming age, your mind is prone to forgetfulness. So, you have forgotten in a night a weighty word conveyed to you.

Mohua answers with her head down: Oh! you are a foreign man and I am a different woman, I die in shamefulness to talk to you.

Nadiarchand consoles Mohua and ensure her of the situation: Filling your pitcher oh beautiful damsel and rippling water with it, Shy don’t you talk with smiling face; there is none here with me.

And Nadiarchand asks the acquaintance of the girl: Who is your mother, girl, and who is your father, where had you been since you came here?

Mohua expresses her helplessness and unfamiliarity and replies: I have no mother and father, no brother born of the same mother, I am a moss in the stream and go on over afloat. And then Mohua relates her own circumstances to Nadiarchand: It was predestined, so I roam about with the gypsies, and bum myself with the flame of mine.

There is no sympathetic soul in this country to whom should I express myself.

Say, who will realize the grief of my burning heart? Oh the young Brahmin, you are happily turning with your beautiful consort. In your own house, the condition congenial to you. The Brahmin says, oh the virgin. you are stone hearted, you utter a lie, I am not yet married.

Mohua retorts: Your parents are hard-hearted and you too are stone, so, much a youthful time of life passes in vain.

Yes, my parents are hard-hearted and myself too is so, If I get a bride like you, I do it instantly.

Oh, shameless Brahmin, you are devoid of any bashfulness, Let the person die with the pitcher entangled in your neck. Oh, the beautiful bride, where should I get pitcher and where to find rope, You yourself become deep river and I plunge to die into your water.

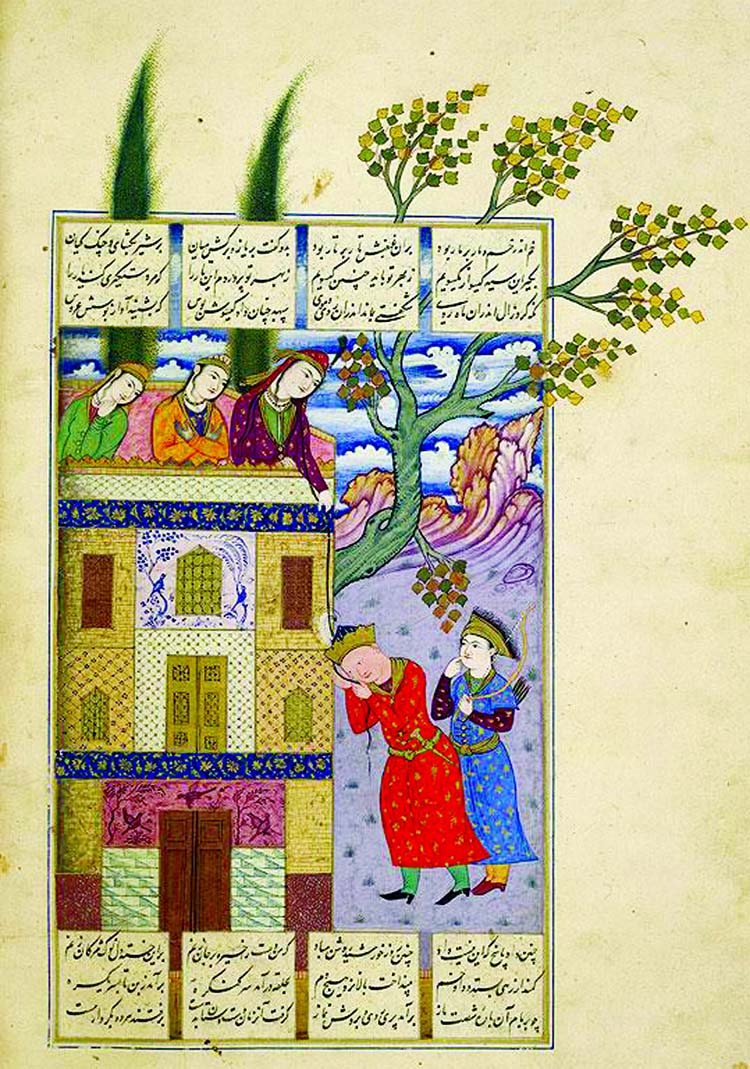

Before we proceed to tragic consequences of the story, let us see this romantic situation of an episode of ‘Shahnama’ by Firdausi and compare the similarity of effect produced there aesthetically.

Hero of the episode of Shahnama, Zal has come to see Rudaba in a moonlit night. From a lofty balcony Rudaba announced felicitation for Zal. The hero with the name of ‘Yazdan’ expresses his legitimate hope: I pray that God in His bounty show me your face in seclusion. Valiant Zal asks Rudaba how he will ascend the high rampart and reach her.

Skillful Rudaba causes to bring down her long tress as a ladder to be climbed by Zal, Rudaba asks: Now quickly come and gird up your loves one and try yourself with thy lions valour and claws of Kayani strength.

Contd on page 9