Jamal Khashoggi had been in the United States for only a few months when the forces he had fled in Saudi Arabia made clear that he would never fully escape.

He was at a friend’s home in suburban Virginia in October 2017 when his phone lit up with an incoming call from Riyadh. On the line was Saud al-Qahtani, a feared lieutenant of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The royal heir and his henchman were at that point in the early stages of a brutal crackdown in the kingdom – arresting rivals, torturing enemies and silencing critics. Khashoggi had previously been banned from writing or even tweeting, but fear that worse could be in store had prompted him to seek refuge in the United States.

Qahtani was uncharacteristically amiable on the call. He told Khashoggi that public comments praising Saudi reforms, including a decision to allow women to drive, had pleased the crown prince. He urged Khashoggi to “keep writing and boasting” about Mohammed’s achievements. While the conversation was cordial, the subtext was clear: Khashoggi no longer lived under Saudi rule, but the country’s most powerful royal was monitoring his every word.

Khashoggi reacted with a combination of the nerve and trepidation that would define the remaining months of his life. He challenged Qahtani about the plight of activists he knew had been imprisoned in the kingdom, according to a friend who witnessed the exchange. But even as he did so, the friend said, “I saw how Jamal’s hand was shaking while holding the phone.”

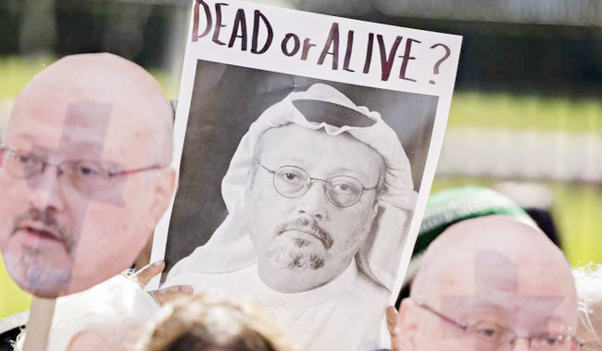

A year later, Khashoggi, 59, would be dead, and Mohammed and Qahtani would be implicated by U.S. intelligence agencies in his killing, which was carried out by a team of assassins dispatched from Riyadh.

The crime has roiled relations between the United States and Saudi Arabia, exposed the ruthless side of a crown prince who was supposed to represent the kingdom’s enlightened future, and revealed the extent to which the Trump administration prioritizes protecting an oil-rich ally over humanitarian concerns.

The case has also taken on the dimensions of a global cause. Khashoggi, a contributing columnist for The Washington Post, was a writer of modest influence beyond the Middle East when he was alive. In death, he has become a symbol of a broader struggle for human rights, as well as a chilling example of the savagery with which autocratic regimes silence voices of dissent.

Khashoggi’s life and work, particularly in his final year, were inevitably more complicated than can be captured in that idealized frame. The complete truth about his fate remains elusive in large measure because of a determined Saudi effort to obscure events – an effort that included relaying false information to executives at The Post in the days after Khashoggi’s death.

This account of his final 18 months, which reveals new details about Khashoggi’s interactions with Saudi officials, his activities over the last year of his life as an exile and his killing, is based on interviews with dozens of associates, friends and officials from countries including Saudi Arabia and the United States as well as Turkey, where Khashoggi was killed and dismembered inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on Oct. 2.

Khashoggi was an advocate for reform in his country, but neither saw himself as a dissident nor believed in bringing radical change to a nation that has operated for the past eight decades as an absolute monarchy.

He relished his newfound freedoms in the United States, and the attention his writing got from a Western audience, but often resisted appeals from associates to be more forceful in his criticism of the kingdom. He was by many accounts depressed by the separation from his country and the strain that his departure and work placed on his family.

Even in exile, Khashoggi remained loyal to Saudi Arabia and reluctant to sever ties to the royal court. In September 2017, at the same time he was embarking on a new role as opinion columnist for The Washington Post, he was pursuing up to $2 million in funding from the Saudi government for a think tank that he proposed to run in Washington, according to documents reviewed by the paper that appear to be part of a proposal he submitted to the Saudi ministry of information.

Khashoggi also sent messages to the Saudi ambassador to the United States, Khaled bin Salman – the brother of the crown prince – expressing his loyalty to the kingdom and reporting on some of his activities in the United States, according to copies reviewed by The Post.

In one case, Khashoggi told the ambassador that he had been contacted by a former FBI agent working on behalf of families of victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks – in which 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi. He said he would to go forward with the meeting and emphasize “the innocence of my country and its leadership.”

But in the conspiracy-driven climate of Middle East politics, Khashoggi came under mounting suspicion because of his writing as well as associations he cultivated over many years with perceived enemies of Riyadh.

Among Khashoggi’s friends in the United States were individuals with real or imagined affiliations with the Islamist group the Muslim Brotherhood, and an Islamic advocacy organization, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, regarded warily for its support of the public uprisings of the Arab Spring. Khashoggi cultivated ties with senior officials in the Turkish government, also viewed with deep distrust by the rulers in Saudi Arabia.