Rayhan Ahmed Topader :

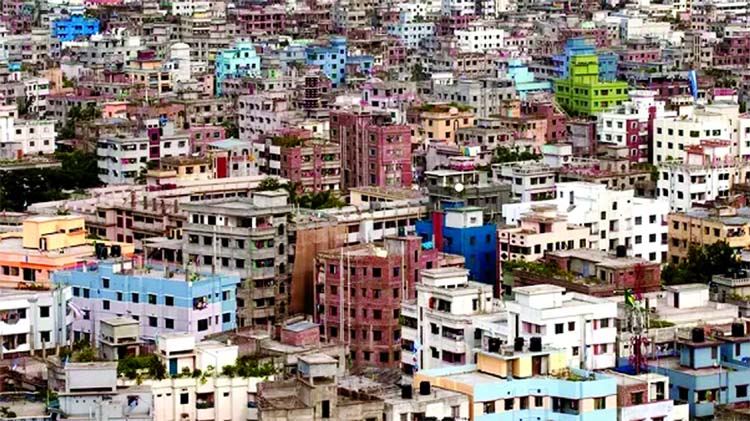

The world’s worst job, global media declared last year after pictures of the workers neck-deep in waste went viral. According to UN Habitat, Dhaka is the world’s most crowded city. With more than 44,500 people sharing each square kilometre of space, and more migrating in from rural areas every day, the capital is literally bursting at the seams and the sewers.

The cleaners, who make about £225 per month, risk their health and their lives to prop up infrastructure that is groaning under the weight of the population. Too many people, too few resources. Overpopulation is usually defined as the state of having more people in one place that can live there comfortably, or more than the resources available can cater for. By that measure, Dhaka is a textbook example.There is cities bigger in size than Dhaka in the world,” says Prof Nurun Nabi, project director at the Department of Population Sciences at the University of Dhaka. But if you talk in terms of the characteristics and nature of the city, Dhaka is the fastest growing megacity in the world, in terms of population size.

“Cities can be densely populated without being overpopulated. Singapore, a small island, has a high population density about 10,200 per sq km but few people would call it overpopulated. The city has grown upwards to accommodate its residents in high-rises, some with rooftop sky-gardens and running tracks. The government has been trying to manage Dhaka city well, but has not been as successful as expected,” says Sujon, the sewer cleaner, over a creamy cup of cha, Bangladeshi tea, in the modest flat he shares with his family in bustling central Dhaka.

Bangladesh’s crowded capital, but the tragedy of 2008 was the worst. After a day of heavy rainfall left the streets flooded as usual seven workers were assigned to clear a blocked manhole in Rampura, in the centre of the city. Normally, cleaners cling to ropes to stop them getting sucked in by surging water when they clear blockages. But these groups were new to the job. They didn’t know about the impending danger or how to work in that situation, says Sujon. So, sewer water swallowed them. Bystanders smashed the road open with hammers and shovels. Eventually, they dragged out three workers, dead. Another four were seriously injured; one later died in hospital. The accident instilled fear in us, and for months we were even afraid to look into the sewers. During Bangladesh’s relentless monsoon season, Dhaka is submerged several times a month.

The overburdened drains clog and the low-lying city fills with water like a bathtub. Newspapers such as the Dhaka Tribune bemoan the inundation with pictures of flooded buses and quotes from peeved commuters and despondent urban experts: Dhaka underwater again; It’s the same old story. On the sides of the roads, in the blinding rain, the ragtag army of sewer cleaners goes to work. Some poke bamboo sticks into the manholes. Others are plunged, half-naked, into the liquid filth and forced to scoop out the sludge with their bare hands.

Outside, painted rickshaws tinkle through narrow, waterlogged streets. While Bangladesh is majority Muslim, like many in his profession, Sujon is Hindu. Hindus were singled out for persecution during the country’s war for independence from Pakistan and remain subject to discrimination. He is also a dalit, belonging to the caste known throughout south Asia as untouchables and consigned to menial jobs. In Bangladesh, they are called by the derogatory term methor those who clean shit. I have inherited this from my forefathers and have no other work skills, says Sujon, who is tall and in his early 40s, with a long, thin face and neat moustache. I have a family to maintain, children to offer education and monthly bills to pay, including rent. I’m forced to do this job, although I know it brings me disrespect and disgrace. It is thankless, dangerous work. A friend of Sujon’s was killed when a septic tank he was cleaning exploded. Recently, Sujon’s brother, Sushil, had to hang on to a leaking gas pipeline while trying to clear a 10-foot-deep manhole. If we had a washer or pump machine, the risk could be reduced,” he says. We could use the pump to dry up the manhole before going down to clear it up. Also, we need to have a ladder to go down.

But we just get an order to get the work done, so we manage people and try to finish it as quickly as possible. Then there are the health effects. Sujon blames a mysterious skin rash on the hours spent submerged. The sewerage lines are acidic and poisonous due to rotten filth. So cleaners are hundred percent sure to have health problems, especially skin problems. Often they don’t realise it at all.

They’ll buy and drink some local liquor, feel dizzy and fall asleep. They’ll be out of this world by then. If they had their senses they would realise the damage being done slowly. To live in Dhaka is to suffer, to varying degrees. The poor are crammed into sprawling shantytowns, where communicable diseases fester and fires sporadically raze homes. Slum-dwellers make up around 40 per cent of the population. The middle and upper classes spend much of their time stuck in interminable traffic jams. The capital regularly tops least livable cities rankings. This year it sat behind Lagos, Nigeria, and the capitals of war-ravaged Libya and Syria. It wasn’t always like this.

In the 1960s, before Bangladesh won independence from Pakistan in 1971, Nabi recalls, it was possible to drive down empty roads in Dhaka. People bathed in Mughal-era canals in the old part of the city, which is still home to centuries-old architecture, although much has been razed in pursuit of development. The canals have been filled in, cutting off a vital source of drainage. Like much of the world; Bangladesh has undergone rapid, unplanned urbanisation.

The economic opportunities conferred by globalisation, as well as climate-induced disasters in rural and coastal areas, have driven millions to seek better fortune in the capital, putting a strain on resources. We can see a huge avalanche coming towards the city from the rural areas, says Nabi. People are pouring, pouring, pouring in. Do we have the housing infrastructure to accommodate them? Where are the facilities for poor people to live?

Bangladesh’s reluctance to decentralise and invest in cities beyond Dhaka has compounded the problem. You go to India, just the neighbouring country, you will find Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, so many cities where you can live, you can survive. Here, we only have Dhaka still. For most of modern history, cities grew out of wealth. Even in more recently developed countries, such as China and Korea, the flight towards cities has largely been in line with income growth. But recent decades have brought a global trend for ‘poor-country urbanisation, in the words of Harvard University economist Edward Glaeser, with the proliferation of low-income megacities. According to Glaeser’s research, in 1960 most countries with a per capita income of less than $1,000 had urbanisation rates of fewer than 10 per cent. By 2011, the urbanisation rate of less developed countries stood at 47 per cent. In other words, urbanisation has outpaced development, resulting in the creation of teeming but dysfunctional megacities such as Lagos, Karachi, Kinshasa and Dhaka. Dense urban populations, Glaeser writes, bring benefits such as social and creative movements as well as scourges like disease and congestion. Almost all of these problems can be solved by competent governments with enough money, he writes. In ancient Rome, Julius Caesar successfully fought traffic by introducing a daytime ban on the driving of carts in the city. Baghdad and Kaifeng, China, meanwhile, were renowned for their waterworks. These places didn’t have wealth, but they did have a competent public sector, writes Glaeser. In much of the developing world today, both are in short supply. In Dhaka, management of the city falls to a chaotic mix of competing bodies.

The lack of coordination between government agencies that provide services is one of the major obstacles. Seven different government departments including two separate mayors are working to combat water-logging, an arrangement that has led to a farcical game of buck-passing. In July, mayor of south Dhaka Sayeed Khokon stood knee-deep in water and said the Water Supply and Sewage Authority (WASA) was liable but could not be seen much at work. WASA subsequently blamed Khokon. Elsewhere, north Dhaka’s late mayor Annisul Huq, also visiting waterlogged areas, turned to a reporter in exasperation and asked: Someone tell me what the solution is? Since natural sources of drainage are scarce, the government has to pump water out of the city through several thousand kilometres of pipeline laid across the city. The reason why there is water congestion in Dhaka city is because it’s a megacity its population growth is too high, he says. WASA once worked for six million people, but today there are about 15 million people that are the reason why the natural water bodies and water drainage systems have been destroyed and housing has been built up. In 2013, the city signed a deal to dredge some of the canals following the example of Sylhet, another Bangladeshi city suffering from water logging but there has been little sign of progress. A Bangladeshi woman holds a glass of contaminated water in Dhaka. Many stories will be written by the people of this nation but dysfunctional administrations have not always been an obstacle to getting things done in Bangladesh.

The country has won praise for its adaptation-focused response to climate change. And some urban planners are rethinking the prevailing negative view of slums, while urbanisation which tends to bring declining birth rates can be a partial solution to overpopulation.

Glaeser points out that social movements formed in the confines of urban areas can have the power to change and discipline governments. In the meantime, however, the unchanged misery of the sewer cleaners serves as a reminder that, as cities grow, they tend to get more unequal. The whole system is against us, against our progress and our development. Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, but our community’s conditions remain the same.

(Rayhan Ahmed Topadar is a writer and columnist)

The world’s worst job, global media declared last year after pictures of the workers neck-deep in waste went viral. According to UN Habitat, Dhaka is the world’s most crowded city. With more than 44,500 people sharing each square kilometre of space, and more migrating in from rural areas every day, the capital is literally bursting at the seams and the sewers.

The cleaners, who make about £225 per month, risk their health and their lives to prop up infrastructure that is groaning under the weight of the population. Too many people, too few resources. Overpopulation is usually defined as the state of having more people in one place that can live there comfortably, or more than the resources available can cater for. By that measure, Dhaka is a textbook example.There is cities bigger in size than Dhaka in the world,” says Prof Nurun Nabi, project director at the Department of Population Sciences at the University of Dhaka. But if you talk in terms of the characteristics and nature of the city, Dhaka is the fastest growing megacity in the world, in terms of population size.

“Cities can be densely populated without being overpopulated. Singapore, a small island, has a high population density about 10,200 per sq km but few people would call it overpopulated. The city has grown upwards to accommodate its residents in high-rises, some with rooftop sky-gardens and running tracks. The government has been trying to manage Dhaka city well, but has not been as successful as expected,” says Sujon, the sewer cleaner, over a creamy cup of cha, Bangladeshi tea, in the modest flat he shares with his family in bustling central Dhaka.

Bangladesh’s crowded capital, but the tragedy of 2008 was the worst. After a day of heavy rainfall left the streets flooded as usual seven workers were assigned to clear a blocked manhole in Rampura, in the centre of the city. Normally, cleaners cling to ropes to stop them getting sucked in by surging water when they clear blockages. But these groups were new to the job. They didn’t know about the impending danger or how to work in that situation, says Sujon. So, sewer water swallowed them. Bystanders smashed the road open with hammers and shovels. Eventually, they dragged out three workers, dead. Another four were seriously injured; one later died in hospital. The accident instilled fear in us, and for months we were even afraid to look into the sewers. During Bangladesh’s relentless monsoon season, Dhaka is submerged several times a month.

The overburdened drains clog and the low-lying city fills with water like a bathtub. Newspapers such as the Dhaka Tribune bemoan the inundation with pictures of flooded buses and quotes from peeved commuters and despondent urban experts: Dhaka underwater again; It’s the same old story. On the sides of the roads, in the blinding rain, the ragtag army of sewer cleaners goes to work. Some poke bamboo sticks into the manholes. Others are plunged, half-naked, into the liquid filth and forced to scoop out the sludge with their bare hands.

Outside, painted rickshaws tinkle through narrow, waterlogged streets. While Bangladesh is majority Muslim, like many in his profession, Sujon is Hindu. Hindus were singled out for persecution during the country’s war for independence from Pakistan and remain subject to discrimination. He is also a dalit, belonging to the caste known throughout south Asia as untouchables and consigned to menial jobs. In Bangladesh, they are called by the derogatory term methor those who clean shit. I have inherited this from my forefathers and have no other work skills, says Sujon, who is tall and in his early 40s, with a long, thin face and neat moustache. I have a family to maintain, children to offer education and monthly bills to pay, including rent. I’m forced to do this job, although I know it brings me disrespect and disgrace. It is thankless, dangerous work. A friend of Sujon’s was killed when a septic tank he was cleaning exploded. Recently, Sujon’s brother, Sushil, had to hang on to a leaking gas pipeline while trying to clear a 10-foot-deep manhole. If we had a washer or pump machine, the risk could be reduced,” he says. We could use the pump to dry up the manhole before going down to clear it up. Also, we need to have a ladder to go down.

But we just get an order to get the work done, so we manage people and try to finish it as quickly as possible. Then there are the health effects. Sujon blames a mysterious skin rash on the hours spent submerged. The sewerage lines are acidic and poisonous due to rotten filth. So cleaners are hundred percent sure to have health problems, especially skin problems. Often they don’t realise it at all.

They’ll buy and drink some local liquor, feel dizzy and fall asleep. They’ll be out of this world by then. If they had their senses they would realise the damage being done slowly. To live in Dhaka is to suffer, to varying degrees. The poor are crammed into sprawling shantytowns, where communicable diseases fester and fires sporadically raze homes. Slum-dwellers make up around 40 per cent of the population. The middle and upper classes spend much of their time stuck in interminable traffic jams. The capital regularly tops least livable cities rankings. This year it sat behind Lagos, Nigeria, and the capitals of war-ravaged Libya and Syria. It wasn’t always like this.

In the 1960s, before Bangladesh won independence from Pakistan in 1971, Nabi recalls, it was possible to drive down empty roads in Dhaka. People bathed in Mughal-era canals in the old part of the city, which is still home to centuries-old architecture, although much has been razed in pursuit of development. The canals have been filled in, cutting off a vital source of drainage. Like much of the world; Bangladesh has undergone rapid, unplanned urbanisation.

The economic opportunities conferred by globalisation, as well as climate-induced disasters in rural and coastal areas, have driven millions to seek better fortune in the capital, putting a strain on resources. We can see a huge avalanche coming towards the city from the rural areas, says Nabi. People are pouring, pouring, pouring in. Do we have the housing infrastructure to accommodate them? Where are the facilities for poor people to live?

Bangladesh’s reluctance to decentralise and invest in cities beyond Dhaka has compounded the problem. You go to India, just the neighbouring country, you will find Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, so many cities where you can live, you can survive. Here, we only have Dhaka still. For most of modern history, cities grew out of wealth. Even in more recently developed countries, such as China and Korea, the flight towards cities has largely been in line with income growth. But recent decades have brought a global trend for ‘poor-country urbanisation, in the words of Harvard University economist Edward Glaeser, with the proliferation of low-income megacities. According to Glaeser’s research, in 1960 most countries with a per capita income of less than $1,000 had urbanisation rates of fewer than 10 per cent. By 2011, the urbanisation rate of less developed countries stood at 47 per cent. In other words, urbanisation has outpaced development, resulting in the creation of teeming but dysfunctional megacities such as Lagos, Karachi, Kinshasa and Dhaka. Dense urban populations, Glaeser writes, bring benefits such as social and creative movements as well as scourges like disease and congestion. Almost all of these problems can be solved by competent governments with enough money, he writes. In ancient Rome, Julius Caesar successfully fought traffic by introducing a daytime ban on the driving of carts in the city. Baghdad and Kaifeng, China, meanwhile, were renowned for their waterworks. These places didn’t have wealth, but they did have a competent public sector, writes Glaeser. In much of the developing world today, both are in short supply. In Dhaka, management of the city falls to a chaotic mix of competing bodies.

The lack of coordination between government agencies that provide services is one of the major obstacles. Seven different government departments including two separate mayors are working to combat water-logging, an arrangement that has led to a farcical game of buck-passing. In July, mayor of south Dhaka Sayeed Khokon stood knee-deep in water and said the Water Supply and Sewage Authority (WASA) was liable but could not be seen much at work. WASA subsequently blamed Khokon. Elsewhere, north Dhaka’s late mayor Annisul Huq, also visiting waterlogged areas, turned to a reporter in exasperation and asked: Someone tell me what the solution is? Since natural sources of drainage are scarce, the government has to pump water out of the city through several thousand kilometres of pipeline laid across the city. The reason why there is water congestion in Dhaka city is because it’s a megacity its population growth is too high, he says. WASA once worked for six million people, but today there are about 15 million people that are the reason why the natural water bodies and water drainage systems have been destroyed and housing has been built up. In 2013, the city signed a deal to dredge some of the canals following the example of Sylhet, another Bangladeshi city suffering from water logging but there has been little sign of progress. A Bangladeshi woman holds a glass of contaminated water in Dhaka. Many stories will be written by the people of this nation but dysfunctional administrations have not always been an obstacle to getting things done in Bangladesh.

The country has won praise for its adaptation-focused response to climate change. And some urban planners are rethinking the prevailing negative view of slums, while urbanisation which tends to bring declining birth rates can be a partial solution to overpopulation.

Glaeser points out that social movements formed in the confines of urban areas can have the power to change and discipline governments. In the meantime, however, the unchanged misery of the sewer cleaners serves as a reminder that, as cities grow, they tend to get more unequal. The whole system is against us, against our progress and our development. Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, but our community’s conditions remain the same.

(Rayhan Ahmed Topadar is a writer and columnist)