Life Desk :

The dramatic impact of cell phone technology on a remote Himalayan kingdom known as the “last Shangri-La” is reflected upon by newspaper editor Tenzing Lamsang.

“Bhutan is jumping from the feudal age to the modern age,” said Lamsang, editor of The Bhutanese biweekly and online journal. “It’s bypassing the industrial age.”

As the last country in the world to get television and one which measures its performance with a “Gross National Happiness” yardstick, Bhutan might have been expected to be a hold-out against mobile technology.

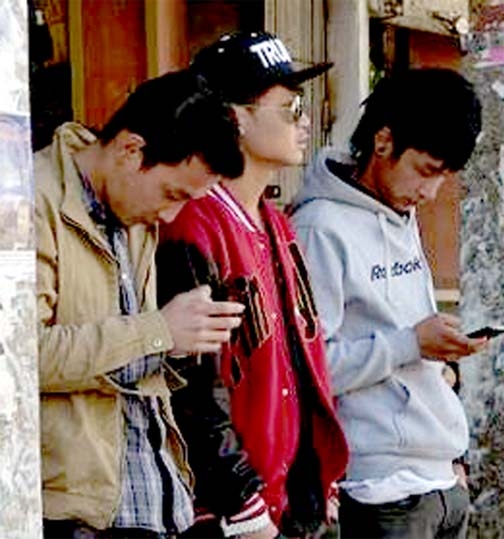

While monks clad in traditional saffron robes remain a common sight on the streets of the capital Thimpu, they now have to dodge cell phone users whose eyes are glued to their screens.

It has a largely rural population of just 750,000, but Bhutan’s two cellular networks have 550,000 subscribers. And the last official figures in 2012 showed more than 120,000 Bhutanese had some kind of mobile Internet connectivity.

Wedged between China and India, the sparsely-populated “Land of the Thunder Dragon” only got its first television sets in 1999, at a time when less than a quarter of households had electricity.

Thanks to a massive investment in hydropower in the following decade-and-a-half, nearly every household is now hooked up to the electricity grid.

The radical change in lifestyle has coincided with an equally dramatic transformation of the political system, with the monarchy ceding absolute power and allowing democratic elections in 2008.

The second nationwide elections took place last year, bringing Tshering Tobgay, a charismatic former civil servant, into office.

In a recent interview with AFP, Tobgay underlined how he regarded technology as a force for good and not something to be resisted.

“Technology is not destructive. It’s good and can contribute to prosperity for Bhutan,” the prime minister said.

“Cellular phones became a reality 10 years ago. We adopted it very well, almost everybody has a cellular phone, that’s the reality.”

The prime minister’s own Facebook page has more than 25,000 followers who can get updates on everything from his talks with Myanmar opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi to photos of police recruits in training.

Influencing government –

Lamsang says social media had “a largely positive role” to play in the fledgling democracy as a way of raising awareness in government circles about a range of issues.

He said there were now 80,000 Facebook users and the number was rising by the day.

“That gives you an idea of how popular the Internet has become in such a short time, he explained.

As the number of households with Internet connections remain limited, Bhutan has seen a proliferation of cybercafes.

Jigme Tamang, an employee at Norling Cyber World in Thimpu, says the best time of year for business comes when students need to check their exam results and then register online for courses.

“We are a little bit worried about the rise of smartphones, because if people can connect through them they will not come here to use our system,” he said.

Eighteen-year-old Suraj Biswa said his smartphone was a fundamental part of his life.

“With my smartphone linked to the Internet, I can use Facebook and various software for editing photos,” said Biswa, a high school student from Samtse in southern Bhutan.

“I use Facebook to exchange with friends or relatives abroad. For example I have cousins in Nepal-without Internet and Facebook I cannot communicate with them.”