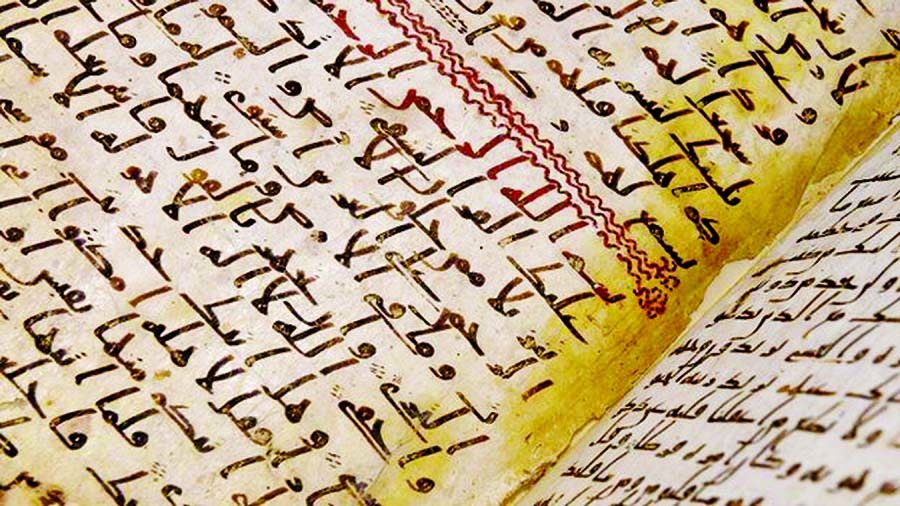

When the University of Birmingham revealed that it had fragments from one of the world’s oldest Qurans, it made headlines around the world. In terms of discoveries, it seemed as unlikely as it was remarkable.

But it raised even bigger questions about the origins of this ancient manuscript.

And there are now suggestions from the Middle East that the discovery could be even more spectacularly significant than had been initially realised. There are claims that these could be fragments from the very first complete version of the Quran, commissioned by Abu Bakr, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad – and that it is “the most important discovery ever for the Muslim world”.This is a global jigsaw puzzle. But some of the pieces have fallen into place. It seems likely the fragments in Birmingham, at least 1,370 years old, were once held in Egypt’s oldest mosque, the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat.

This is because academics are increasingly confident the Birmingham manuscript has an exact match in the National Library of France, the Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

The library points to the expertise of Francois Deroche, historian of the Quran and academic at the College de France, and he confirms the pages in Paris are part of the same Quran as Birmingham’s.

Alba Fedeli, the researcher who first identified the manuscript in Birmingham, is also sure it is the same as the fragments in Paris.

The significance is that the origin of the manuscript in Paris is known to have been the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat.

The French part of this manuscript was brought to Europe by Asselin de Cherville, who served as a vice consul in Egypt when the country was under the control of Napoleon’s armies in the early 19th Century.

Prof Deroche says Asselin de Cherville’s widow seemed to have tried to sell this and other ancient Islamic manuscripts to the British Library in the 1820s, but they ended up in the national library in Paris, where they have remained ever since.

Prof Deroche says later in the 19th Century manuscripts were transferred from the mosque in Fustat to the national library in Cairo.

Along the way, “some folios must have been spirited away” and entered the antiquities market.

These were presumably sold and re-sold, until in the 1920s they were acquired by Alphonse Mingana and brought to Birmingham.

Mingana was an Assyrian, from what is now modern-day Iraq, whose collecting trips to the Middle East were funded by the Cadbury family.

“Of course, no official traces of this episode were left, but it should explain how Mingana got some leaves from the Fustat trove,” says Prof Deroche, who holds the legion of honour for his academic work.

And tantalisingly, he says other similar material, sold to western collectors could, still come to light.

But what remains much more contentious is the dating of the manuscript in Birmingham.

What was really startling about the Birmingham discovery was its early date, with radiocarbon testing putting it between 568 and 645. The latest date in the range is 13 years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632. David Thomas, Birmingham University’s professor of Christianity and Islam, explained how much this puts the manuscript into the earliest years of Islam: “The person who actually wrote it could well have known the Prophet Muhammad.”

But the early date contradicts the findings of academics who have based their analysis on the style of the text.

Mustafa Shah, from the Islamic studies department at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, says the “graphical evidence”, such as how the verses are separated and the grammatical marks, show this is from a later date.

In this early form of Arabic, writing styles developed and grammatical rules changed, and Dr Shah says the Birmingham manuscript is simply inconsistent with such an early date.

Prof Deroche also says he has “reservations” about radiocarbon dating and there have been cases where manuscripts with known dates have been tested and the results have been incorrect.

But staff at Oxford University’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, which dated the parchment, are convinced their findings are correct, no matter how inconvenient.

Researcher David Chivall says the accuracy of dating has improved in recent years, with a much more reliable approach to removing contamination from samples. In the case of the Birmingham Quran, Mr Chivall says the latter half of the age range is more likely, but the overall range is accurate to a probability of 95%.

It is the same level of confidence given to the dating of the bones of Richard III, also tested at the Oxford laboratory. “We’re as confident as we can be that the dates are accurate.”

And academic opinions can change. Dr Shah says until the 1990s the dominant academic view in the West was that there was no complete written version of the Quran until the 8th Century.

But researchers have since overturned this consensus, proving it “completely wrong” and providing more support for the traditional Muslim account of the history of the Quran.

The corresponding manuscript in Paris, which could help to settle the argument about dates, has not been radiocarbon tested.

There are only two leaves in Birmingham, but Prof Thomas says the complete collection would have been about 200 separate leaves. “It would have been a monumental piece of work,” he said.

And it raises questions about who would have commissioned the Quran and been able to mobilise the resources to produce it. Jamal bin Huwareib, managing director of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation, an education foundation set up by the ruler of the UAE, says the evidence points to an even more remarkable conclusion.

He believes the manuscript in Birmingham is part of the first comprehensive written version of the Quran assembled by Abu Bakr, the Muslim caliph who ruled between 632 and 634.

“It’s the most important discovery ever for the Muslim world,” says Mr bin Huwareib, who has visited Birmingham to examine the manuscript. “I believe this is the Quran of Abu Bakr.”

He says the high quality of the hand writing and the parchment show this was a prestigious work created for someone important – and the radiocarbon dating shows it is from the earliest days of Islam.

“This version, this collection, this manuscript is the root of Islam, it’s the root of the Quran,” says Mr bin Huwareib. “This will be a revolution in studying Islam.”

This would be an unprecedented find. Prof Thomas says the dating fits this theory but “it’s a very big leap indeed”. There are other possibilities. The radiocarbon dating is based on the death of the animal whose skin was used for the parchment, not when the writing was completed, which means the manuscript could be a few years later than the age range ending in 645, with Prof Thomas suggesting possible dates of 650 to 655.

This would overlap with the production of copies of the Quran during the rule of the caliph Uthman, between 644 and 656, which were intended to produce an accurate, standardised version to be sent to Muslim communities.

If the Birmingham manuscript was a fragment of one of these copies it would also be a spectacular outcome.

It’s not possible to definitively prove or disprove such theories.

But Joseph Lumbard, professor in the department of Arabic and translation studies at the American University of Sharjah, says if the early dating is correct then nothing should be ruled out.

“I would not discount that it could be a fragment from the codex collected by Zayd ibn Thabit under Abu Bakr.

“I would not discount that it could be a copy of the Uthmanic codex. “I would not discount Deroche’s argument either, he is such a leader in this field,” says Prof Lumbard. He also warns of evidence being cherry-picked to support experts’ preferred views.

Prof Thomas says there could also have been copies made from copies and perhaps the Birmingham manuscript is from a copy made specially for the mosque in Fustat.

Jamal bin Huwaireb sees the discovery of such a “priceless manuscript” in the UK, rather than a Muslim country, as sending a message of mutual tolerance between religions. “We need to respect each other, work together, we don’t need conflict.” But don’t expect any end to the arguments over this ancient document.