NY Times :

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away, there stood emerald peaks woven with crystalline rivers, hillsides garlanded with stone villages, and canyons joined by lofty bridges arcing toward the heavens. This enchanting realm even had a suitably enchanting name: Bosnia and Herzegovina, as melodious as Narnia, Utopia or Shangri-La, worlds that exist in the imagination, not on maps.

But Bosnia, of course, isn’t exactly a fairy tale. As much as I’d prepared myself, it didn’t register when I first glimpsed it: an apartment block a few minutes from Sarajevo’s airport, its otherwise unremarkable facade speckled with unseemly blisters. Soon after, a building with a gaping chasm where a window might have once been, and then another, with chunks of plaster gouged out like missing teeth.

“Are those from the war?” I asked my cab driver. He didn’t understand me or chose not to respond, but some questions don’t need answers. The lingering scars are reminders of an evil transpired not once upon a time but just a quarter of a century ago, from curses that were the doing of neighbours and friends, not the spell of some spiteful witch. And yet, in Bosnia, I found scenery that fit the platonic ideal of a fairy tale, a dreamy dominion punctuated by spindly minarets instead of crosses. I could relate more to this landscape than to those of the fables of my childhood, in which valiant knights pursuing fair maidens were usually fresh off the horse from bloody quests that had a little something to do with vanquishing Islam. In a time when much of Europe is racked with a suspicion of my faith as a foreign entity breaching its shores, I’d come to Bosnia to see what a homegrown Muslim community, with 500 years of history rooted in the heart of Europe, might feel like.

Sarajevo, a City Reborn

In the Bascarsija, the labyrinthine old quarter at the heart of Sarajevo, I strolled through various lanes of the 16th-century, Ottoman-era bazaar that had once been demarcated for different artisans: Coppersmiths would tak-tak-tak away at pots on Kazandziluk; blacksmiths forged iron tools on Kovaci; tanners hawked leather goods on Saraci; and shoemakers converged on Cizmedziluk.

These days, the shops blur into an endless expanse of tea sets, leather slippers and artwork that I’m assured is completely original (unlike those identical prints next door, of course). But what caught my eye most were the door knockers embellished with brass and silver. The zvekir is a symbol of the city, featuring prominently on the coat of arms of Sarajevo Canton; it is, I was told by a tour guide, a tribute to the hospitality of the Bosnians. “Maybe because of the Islamic roots here, the people are warm,” Reshad Strik, owner of a cafe called Ministry of Cejf on the fringes of Bascarsija, told me over a pot of Bosnian coffee, thick with bitter sediment reminiscent of its Turkish forebear. “Maybe that’s why there’s war here all the time. We’re too welcoming.”

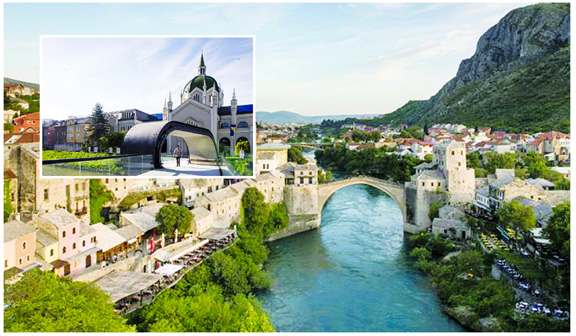

Crossing a fairy-tale bridge to Mostar

The fairy tale continued as I crossed over to the southern region of Herzegovina, where the craggy peaks and virgin forests and translucent rivers could have been immortalized in illustrations for ‘Sleeping Beauty’ or ‘Cinderella’ – that is, if the artist erased the pencil-thin minarets darting above the trees. I prayed inside the Sisman Pasa mosque in Pocitelj, a charming stone village that cascades down the contours of a sheer cliff. In Blagaj, at a 15th-century dervish monastery above the river Buna in the shadow of a towering bluff, I read the Arabic ‘hu,’ a common Sufi dhikr, or chant. But amid the magic, darkness still loomed: In Konjic, as I fantasized about putting a down payment on a lovely riverside cottage, I glimpsed the scorched stub of a bombed-out minaret behind it. It was one of 614 mosques destroyed across the country during the war.

While invaders have long helped themselves to Bosnia’s hospitality, tourists seeking to conquer new lands via Instagram feeds have mostly bypassed it. Twenty-four years after the end of the war, next-door Croatia has emerged as a bucket-list topper, welcoming nearly 14 million tourists in 2016. A glance at a map suggests why: Croatia won big in the cartography lottery, boomeranging around Bosnia and sweeping up most of the Balkan coastline. But its neighbour remains largely overlooked – in 2016, Bosnia had fewer than 1 million visitors. A year’s worth of tourists seemed to have joined me in Mostar on the day I arrived. Thousands of day trippers flood the historic quarter to cross the 16th-century Stari Most bridge, receding come evening to nearby Dubrovnik or Split. The allure is obvious – when I beheld the majestic link that leaps gracefully across two cliffs wrenched apart by the Neretva River, the number of selfie sticks seemed not nearly high enough for a sight so ethereal.

Places to Stay

In Sarajevo, the Aziza Hotel is a sweet family-run hotel a short walk uphill from the Bascarsija (the bazaar). Information: Saburina 2; hotelaziza.ba. Doubles from around 40 euros (or about $45) in low season, 80 euros in the summer. To be close to all the main sites, stay in or near the Bascarsija – Airbnb has entire apartments in this neighbourhood for around $25 per night.

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away, there stood emerald peaks woven with crystalline rivers, hillsides garlanded with stone villages, and canyons joined by lofty bridges arcing toward the heavens. This enchanting realm even had a suitably enchanting name: Bosnia and Herzegovina, as melodious as Narnia, Utopia or Shangri-La, worlds that exist in the imagination, not on maps.

But Bosnia, of course, isn’t exactly a fairy tale. As much as I’d prepared myself, it didn’t register when I first glimpsed it: an apartment block a few minutes from Sarajevo’s airport, its otherwise unremarkable facade speckled with unseemly blisters. Soon after, a building with a gaping chasm where a window might have once been, and then another, with chunks of plaster gouged out like missing teeth.

“Are those from the war?” I asked my cab driver. He didn’t understand me or chose not to respond, but some questions don’t need answers. The lingering scars are reminders of an evil transpired not once upon a time but just a quarter of a century ago, from curses that were the doing of neighbours and friends, not the spell of some spiteful witch. And yet, in Bosnia, I found scenery that fit the platonic ideal of a fairy tale, a dreamy dominion punctuated by spindly minarets instead of crosses. I could relate more to this landscape than to those of the fables of my childhood, in which valiant knights pursuing fair maidens were usually fresh off the horse from bloody quests that had a little something to do with vanquishing Islam. In a time when much of Europe is racked with a suspicion of my faith as a foreign entity breaching its shores, I’d come to Bosnia to see what a homegrown Muslim community, with 500 years of history rooted in the heart of Europe, might feel like.

Sarajevo, a City Reborn

In the Bascarsija, the labyrinthine old quarter at the heart of Sarajevo, I strolled through various lanes of the 16th-century, Ottoman-era bazaar that had once been demarcated for different artisans: Coppersmiths would tak-tak-tak away at pots on Kazandziluk; blacksmiths forged iron tools on Kovaci; tanners hawked leather goods on Saraci; and shoemakers converged on Cizmedziluk.

These days, the shops blur into an endless expanse of tea sets, leather slippers and artwork that I’m assured is completely original (unlike those identical prints next door, of course). But what caught my eye most were the door knockers embellished with brass and silver. The zvekir is a symbol of the city, featuring prominently on the coat of arms of Sarajevo Canton; it is, I was told by a tour guide, a tribute to the hospitality of the Bosnians. “Maybe because of the Islamic roots here, the people are warm,” Reshad Strik, owner of a cafe called Ministry of Cejf on the fringes of Bascarsija, told me over a pot of Bosnian coffee, thick with bitter sediment reminiscent of its Turkish forebear. “Maybe that’s why there’s war here all the time. We’re too welcoming.”

Crossing a fairy-tale bridge to Mostar

The fairy tale continued as I crossed over to the southern region of Herzegovina, where the craggy peaks and virgin forests and translucent rivers could have been immortalized in illustrations for ‘Sleeping Beauty’ or ‘Cinderella’ – that is, if the artist erased the pencil-thin minarets darting above the trees. I prayed inside the Sisman Pasa mosque in Pocitelj, a charming stone village that cascades down the contours of a sheer cliff. In Blagaj, at a 15th-century dervish monastery above the river Buna in the shadow of a towering bluff, I read the Arabic ‘hu,’ a common Sufi dhikr, or chant. But amid the magic, darkness still loomed: In Konjic, as I fantasized about putting a down payment on a lovely riverside cottage, I glimpsed the scorched stub of a bombed-out minaret behind it. It was one of 614 mosques destroyed across the country during the war.

While invaders have long helped themselves to Bosnia’s hospitality, tourists seeking to conquer new lands via Instagram feeds have mostly bypassed it. Twenty-four years after the end of the war, next-door Croatia has emerged as a bucket-list topper, welcoming nearly 14 million tourists in 2016. A glance at a map suggests why: Croatia won big in the cartography lottery, boomeranging around Bosnia and sweeping up most of the Balkan coastline. But its neighbour remains largely overlooked – in 2016, Bosnia had fewer than 1 million visitors. A year’s worth of tourists seemed to have joined me in Mostar on the day I arrived. Thousands of day trippers flood the historic quarter to cross the 16th-century Stari Most bridge, receding come evening to nearby Dubrovnik or Split. The allure is obvious – when I beheld the majestic link that leaps gracefully across two cliffs wrenched apart by the Neretva River, the number of selfie sticks seemed not nearly high enough for a sight so ethereal.

Places to Stay

In Sarajevo, the Aziza Hotel is a sweet family-run hotel a short walk uphill from the Bascarsija (the bazaar). Information: Saburina 2; hotelaziza.ba. Doubles from around 40 euros (or about $45) in low season, 80 euros in the summer. To be close to all the main sites, stay in or near the Bascarsija – Airbnb has entire apartments in this neighbourhood for around $25 per night.