AP, Moscow :

They played key roles in Russia’s 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, which triggered a civil war that killed millions, devastated the country and redrew its borders. A century later, their descendants say these historic wounds have not healed.

As Russia approaches the centennial of the uprising, it has struggled to come to terms with the legacy of those who remade the nation. The Kremlin is avoiding any official commemoration of the anniversary, tip-toeing around the event that remains polarizing for many and could draw unwelcome parallels to the present.

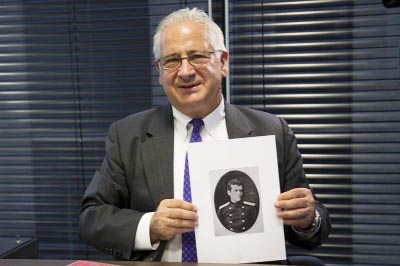

Alexis Rodzianko, whose great-grandfather was speaker of the pre-revolutionary Russian parliament and pushed Czar Nicholas II to abdicate but later regretted it, sees the revolution as a calamity that threw Russia backward.

“Any evolutionary development would have been better than what happened,” Rodzianko, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia, told The Associated Press. “The main lesson I certainly would hope is that Russia never tries that again.” He said the revolution and the civil war, combined with the devastation of World War II and the overall legacy of the Soviet system, eroded Russia’s potential and left its economy a fraction of what it could have been.

A similar view is held by Vyacheslav Nikonov, a Kremlin-connected lawmaker whose grandfather, Vyacheslav Molotov, played an important role in staging the Bolshevik power grab on Nov. 7, 1917, and served as a member of the Communist leadership for four decades.

Nikonov describes the revolution as “one of the greatest tragedies of Russian history.”

The anniversary is a tricky moment for President Vladimir Putin.

While he has been critical of revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin, Putin can’t denounce the event that gave birth to the Soviet Union and is still revered by many of his supporters. But Putin, a KGB veteran, disdains any popular uprisings, and he certainly wouldn’t praise the revolution, which destroyed the Russian empire.

“The last thing the Kremlin needs is another revolution. The last thing Russia needs is another revolution,” Rodzianko said. “And celebrating the revolution saying: ‘Hey, what a great thing!’ is a little bit encouraging what they don’t want, and so they are definitely confused.”

He believes the befuddled attitude to the anniversary reflects a national trauma that still hurts.

“To me, it’s a sign that people aren’t quite over it. For Russia, it’s a wound that is far from healed,” he said.

The Kremlin has blamed the U.S. for helping to oust some unpopular rulers in former Soviet nations and for instigating Arab Spring democracy uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa. Putin has also accused Washington of encouraging big demonstrations against him in Moscow in 2011-2012.

Nikonov echoes Putin’s claims of outside meddling.

“Our Western friends are spending a lot of money on all sort of organizations, which are working to undermine the Russian government,” he said.

The government’s low-key treatment of the centennial reflects deep divisions in Russia over the revolution, said Nikonov, who chairs a committee on education and science in the Kremlin-controlled lower house of parliament.

A nationwide poll last month by the research company VTsIOM showed opinions over the revolution split almost evenly, with 46 percent saying it served interests of the majority and the same number responding that only a few benefited; the rest were undecided. The poll of 1,800 people had a margin of error of no more than 2.5 percentage points.

During Soviet times, Nov. 7 was known as Revolution Day and featured grand military parades and demonstrations on Red Square. After the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia stopped celebrating it, although the Communists still marked it.

“There is no way you can celebrate the revolution so that the majority of the public would support that,” Nikonov said. “There is no common interpretation of history of the revolution, and I don’t think it’s possible in any foreseeable future. So I think the best way for the government in that situation is just keep a low profile.”

Vyacheslav Molotov remained a steadfast believer in the Communist cause until his 1986 death in Moscow at age 96. Nikonov, his grandson, believes the revolution denied Russia a victory in World War I.

“At the beginning of the year, Russia was one of the great powers with perfect chances of winning the war in a matter of months,” he said. “Then the government was destroyed. By the end of the year, Russia wasn’t a power, it was incapable of anything.”

Nikonov insists the current political system can meet any challenges, adding: “I don’t think that Russia faces any dangers to its stability now.”

Putin has famously described the 1991 Soviet collapse as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century,” but he also has deplored the 1917 revolution. This ambivalence is rooted in his desire to tap the achievements of both the czarist and the Soviet empires as part of restoring Russia’s international clout and prestige.

They played key roles in Russia’s 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, which triggered a civil war that killed millions, devastated the country and redrew its borders. A century later, their descendants say these historic wounds have not healed.

As Russia approaches the centennial of the uprising, it has struggled to come to terms with the legacy of those who remade the nation. The Kremlin is avoiding any official commemoration of the anniversary, tip-toeing around the event that remains polarizing for many and could draw unwelcome parallels to the present.

Alexis Rodzianko, whose great-grandfather was speaker of the pre-revolutionary Russian parliament and pushed Czar Nicholas II to abdicate but later regretted it, sees the revolution as a calamity that threw Russia backward.

“Any evolutionary development would have been better than what happened,” Rodzianko, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia, told The Associated Press. “The main lesson I certainly would hope is that Russia never tries that again.” He said the revolution and the civil war, combined with the devastation of World War II and the overall legacy of the Soviet system, eroded Russia’s potential and left its economy a fraction of what it could have been.

A similar view is held by Vyacheslav Nikonov, a Kremlin-connected lawmaker whose grandfather, Vyacheslav Molotov, played an important role in staging the Bolshevik power grab on Nov. 7, 1917, and served as a member of the Communist leadership for four decades.

Nikonov describes the revolution as “one of the greatest tragedies of Russian history.”

The anniversary is a tricky moment for President Vladimir Putin.

While he has been critical of revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin, Putin can’t denounce the event that gave birth to the Soviet Union and is still revered by many of his supporters. But Putin, a KGB veteran, disdains any popular uprisings, and he certainly wouldn’t praise the revolution, which destroyed the Russian empire.

“The last thing the Kremlin needs is another revolution. The last thing Russia needs is another revolution,” Rodzianko said. “And celebrating the revolution saying: ‘Hey, what a great thing!’ is a little bit encouraging what they don’t want, and so they are definitely confused.”

He believes the befuddled attitude to the anniversary reflects a national trauma that still hurts.

“To me, it’s a sign that people aren’t quite over it. For Russia, it’s a wound that is far from healed,” he said.

The Kremlin has blamed the U.S. for helping to oust some unpopular rulers in former Soviet nations and for instigating Arab Spring democracy uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa. Putin has also accused Washington of encouraging big demonstrations against him in Moscow in 2011-2012.

Nikonov echoes Putin’s claims of outside meddling.

“Our Western friends are spending a lot of money on all sort of organizations, which are working to undermine the Russian government,” he said.

The government’s low-key treatment of the centennial reflects deep divisions in Russia over the revolution, said Nikonov, who chairs a committee on education and science in the Kremlin-controlled lower house of parliament.

A nationwide poll last month by the research company VTsIOM showed opinions over the revolution split almost evenly, with 46 percent saying it served interests of the majority and the same number responding that only a few benefited; the rest were undecided. The poll of 1,800 people had a margin of error of no more than 2.5 percentage points.

During Soviet times, Nov. 7 was known as Revolution Day and featured grand military parades and demonstrations on Red Square. After the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia stopped celebrating it, although the Communists still marked it.

“There is no way you can celebrate the revolution so that the majority of the public would support that,” Nikonov said. “There is no common interpretation of history of the revolution, and I don’t think it’s possible in any foreseeable future. So I think the best way for the government in that situation is just keep a low profile.”

Vyacheslav Molotov remained a steadfast believer in the Communist cause until his 1986 death in Moscow at age 96. Nikonov, his grandson, believes the revolution denied Russia a victory in World War I.

“At the beginning of the year, Russia was one of the great powers with perfect chances of winning the war in a matter of months,” he said. “Then the government was destroyed. By the end of the year, Russia wasn’t a power, it was incapable of anything.”

Nikonov insists the current political system can meet any challenges, adding: “I don’t think that Russia faces any dangers to its stability now.”

Putin has famously described the 1991 Soviet collapse as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century,” but he also has deplored the 1917 revolution. This ambivalence is rooted in his desire to tap the achievements of both the czarist and the Soviet empires as part of restoring Russia’s international clout and prestige.