Amanda Heidt :

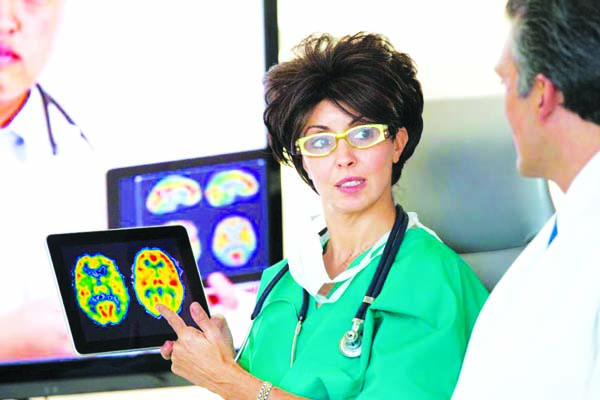

Newly described case reports add to growing evidence that COVID-19 infections can result in severe, long-lasting neurological complications-including inflammation, psychosis, delirium, nerve damage, and strokes-even among patients experiencing mild cases of the virus with few other symptoms. In some instances, the new study claims, these neurological effects were the first manifestation of the disease.

In a paper published on July 8 in the journal Brain, neurologists in the UK noted an uptick this spring in cases of a potentially fatal condition called acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). While ADEM is usually diagnosed in younger children after a viral infection, researchers at the college’s Institute of Neurology tell The Guardian that they saw two or three cases per week among coronavirus patients during April and May. Ordinarily, the hospital sees about two ADEM cases per month among adults.

“We’re seeing things in the way Covid-19 affects the brain that we haven’t seen before with other viruses,” says Michael Zandi, a consulting neurologist at the university’s hospital and the study’s senior author. “What we’ve seen with some of these Adem patients, and in other patients, is you can have severe neurology, you can be quite sick, but actually have trivial lung disease,” he adds.

See “Lost Smell and Taste Hint COVID-19 Can Target the Nervous System”

COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory disease that attacks the lungs, but it has also manifested seemingly unrelated symptoms, such as a loss of taste and smell or memory loss, that can persist for months beyond the initial diagnosis. These oddities suggest a neurological source.

The study detailed the neurological symptoms of 43 patients hospitalized in the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London with confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19. A dozen were diagnosed with inflammation of the central nervous system, including nine cases of ADEM. A further 10 patients experienced delirium or psychosis. Eight patients suffered strokes, including one that was fatal, and another eight had peripheral nerve damage.

At least two patients also developed strange behaviors shortly after being discharged from the hospital. One woman, as described in the paper, repeatedly donned and took off her coat, and began hallucinating lions and monkeys inside her home. Another woman became drowsy and ultimately needed emergency surgery to relieve the pressure on her brain.

The full long-term effects of these symptoms may not be realized for years, says Zandi. Many patients are currently too sick to place inside brain scanners, The Guardian reports, meaning the full extent of neurological symptoms remains unknown. In addition, some changes may be more subtle and happen over time. Speaking to Reuters, Adrian Owen, a neuroscientist at Western University who was not involved in the study, expressed concern over their potential to severely affect the quality of life for recovering patients.

“My worry is that we have millions of people with COVID-19 now. And if in a year’s time we have 10 million recovered people, and those people have cognitive deficits . . . then that’s going to affect their ability to work and their ability to go about activities of daily living,” Owen says.

See “Severe Neurological Ailments Reported in COVID-19 Patients”

His worry has precedent, as evidenced by the 1918 influenza pandemic that infected one-third of the world’s population. In the decades after, up to 1 million people developed a brain disorder called encephalitis lethargica, known more commonly as “sleepy sickness.” Some scholars have linked the two events together, although the evidence remains inconclusive.

“Whether we will see an epidemic on a large scale of brain damage linked to the pandemic-perhaps similar to the encephalitis lethargica outbreak in the 1920s and 1930s after the 1918 influenza pandemic-remains to be seen,” Zandi tells Reuters.

The authors of the study are now pushing for larger, possibly global efforts to track neurological symptoms. Zandi tells The Guardian that health professionals should begin incorporating cognitive function into their patient assessments, while his coauthor Ross Paterson, a neurodegenerative specialist at University College London, says early diagnosis is key. “Given that the disease has only been around for a matter of months, we might not yet know what long-term damage COVID-19 can cause,” Paterson tells Reuters. “Doctors need to be aware of possible neurological effects, as early diagnosis can improve patient outcomes.”